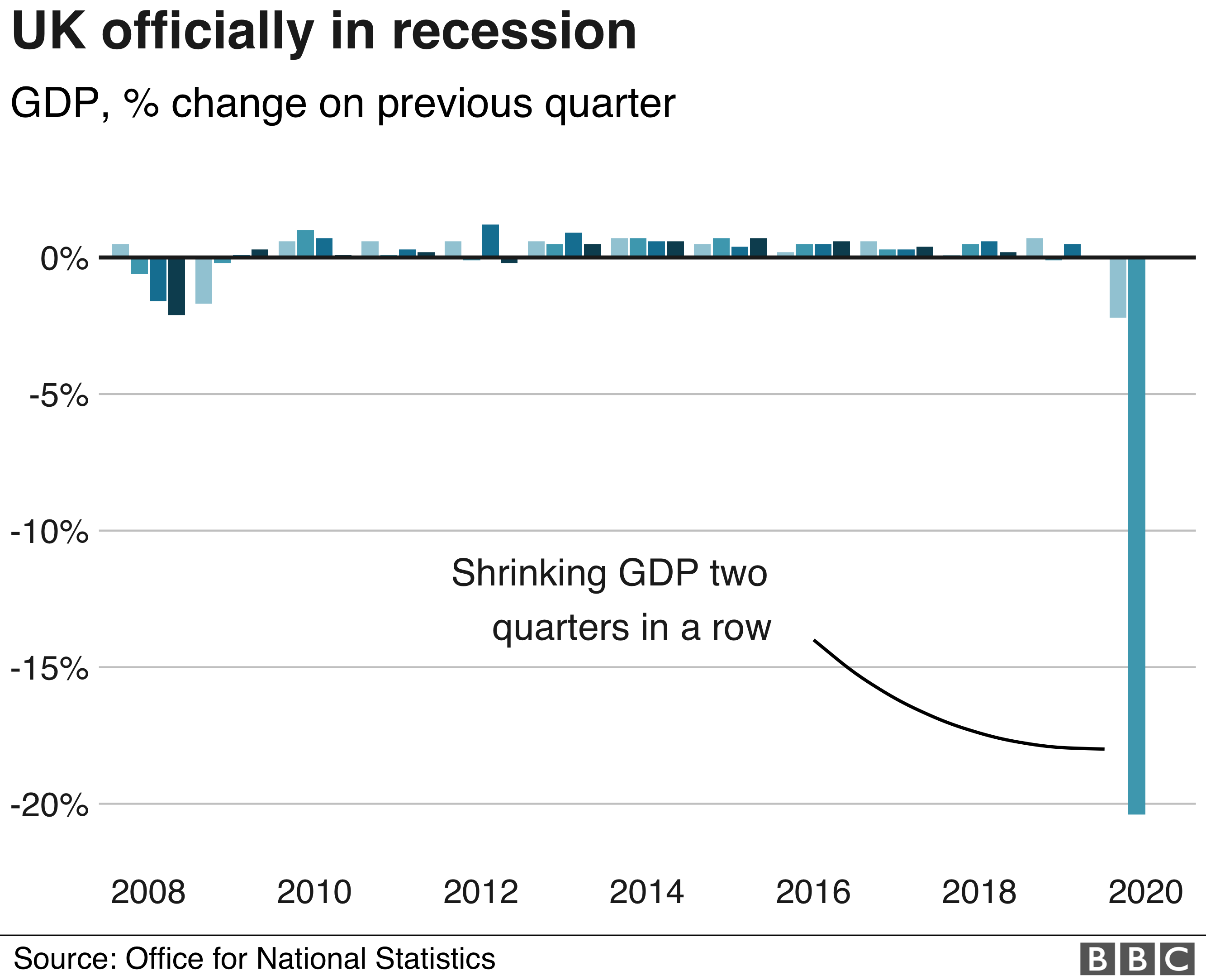

The UK economy suffered its biggest slump on record between April and June as coronavirus lockdown measures pushed the country officially into recession.

The economy shrank 20.4% compared with the first three months of the year.

Household spending plunged as shops were ordered to close, while factory and construction output also fell.

This pushed the UK into its first technical recession – defined as two consecutive quarters of economic decline – since 2009.

Is there any sign of things getting better?

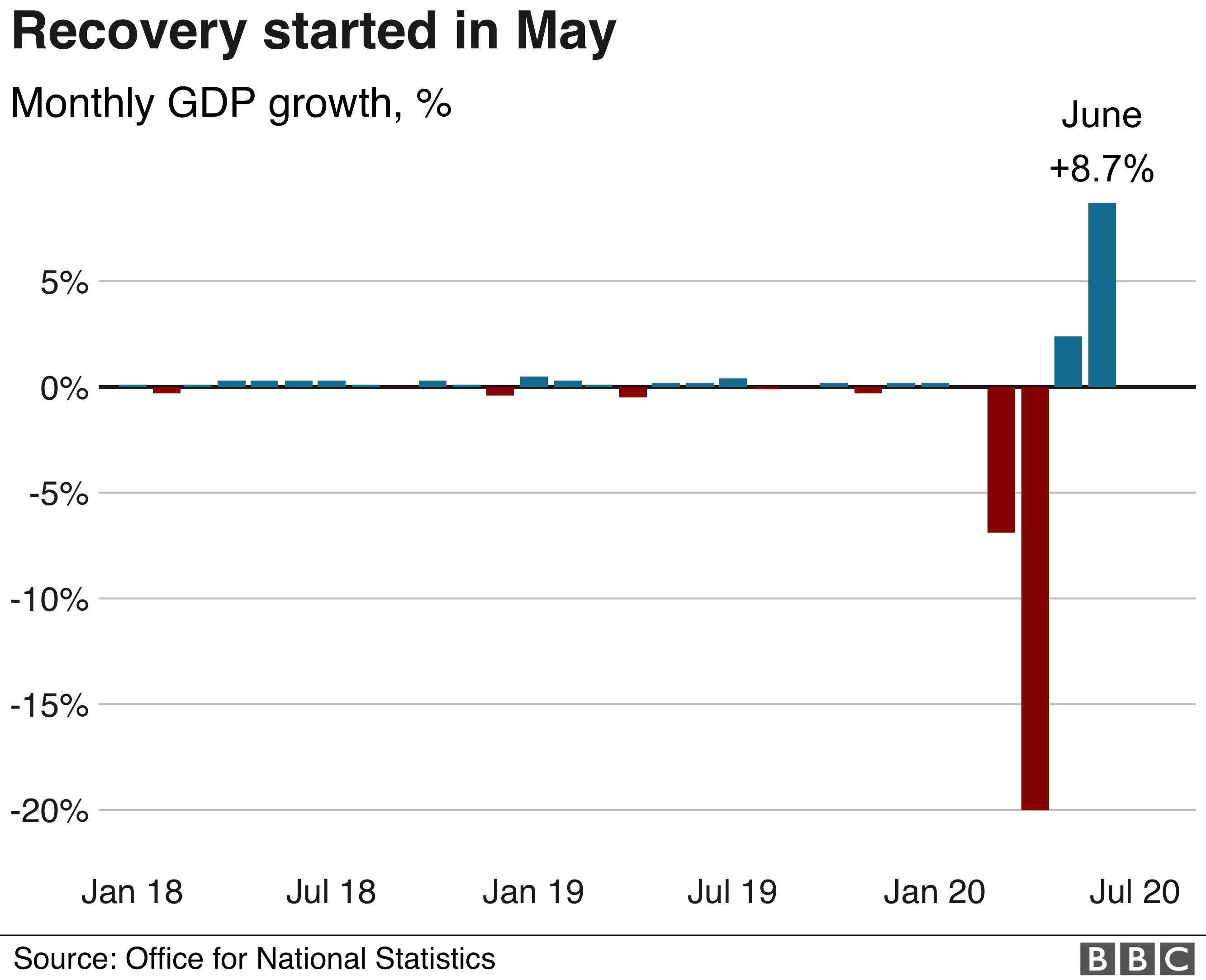

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) said the economy bounced back in June as government restrictions on movement started to ease.

On a month-on-month basis, the economy grew by 8.7% in June, after growth of 1.8% in May.

But Jonathan Athow, deputy national statistician for economic statistics, said: “Despite this, gross domestic product (GDP) in June still remains a sixth below its level in February, before the virus struck.”

Which parts of the economy have suffered most?

The ONS said the collapse in output was driven by the closure of shops, hotels, restaurants, schools and car repair shops.

The services sector, which powers four-fifths of the economy, suffered the biggest quarterly decline on record.

Factory shutdowns also resulted in the slowest car production since 1954.

The economic decline was concentrated in April, at the height of lockdown.

- What is a recession?

- How could a recession affect me?

- PM warns of ‘long, long way to go’ for UK economy

Clothes stores, bookshops and other non-essential retailers opened their doors in England on 15 June, while construction work jumped after large declines in the previous two months.

What is the government doing about it?

Chancellor Rishi Sunak has said the economic slump will lead to more job losses in the coming months.

Official jobs figures released on Tuesday showed the number of people in work fell by 220,000 between April and June.

But in a BBC interview on Wednesday, he did not waver on ending the government’s furlough scheme of job subsidies, which is winding down and is due to end entirely after October.

“I think most people would agree that that’s not something that is sustainable indefinitely,” he told the BBC.

The chancellor said the government should not pretend that “absolutely everybody can and will be able to go back to the job they had” and said there would be support for creating jobs in new areas.

He said there would be a “fiscal event” in the autumn, addressing reports that the Budget planned for then might be scrapped because of fears of a second wave of the pandemic.

He added that there would not be a return to austerity – but acknowledged that public spending had taken a huge hit and there would be difficult choices ahead.

What are other people saying?

Business groups urged the government to do more to support the economic recovery.

Alpesh Paleja, an economist at the Confederation of British Industry, said many companies were struggling to pay their bills on time.

He said: “A sustained recovery is by no means assured. The dual threats of a second wave and slow progress over Brexit negotiations are also particularly concerning.”

The Institute of Directors (IoD) said mounting debts made it difficult for businesses to push ahead with spending plans.

Chief economist Tej Parikh said: “Job losses have been mounting and may only increase as we reach the end of the furlough scheme. The pile of debt businesses have had to take on could also cause a lasting hangover.”

It is urging the government to cut employers’ national insurance contributions, which would make it cheaper to hire. It also said further grants for small businesses would help them through the pandemic.

While more recent data suggest the recovery is gaining traction, the Bank of England does not expect the economy to get back to its pre-pandemic size until the end of next year.

The Office for Budget Responsibility, the government’s official forecaster, expects the recovery to take even longer.

How does the UK compare with other nations?

The UK’s slump is one of the biggest among advanced economies, according to preliminary estimates.

The economy is more than a fifth smaller than it was at the end of last year. This fall is not as bad as the 22.7% decline in Spain, but about twice the size of contractions in Germany and the US.

The Bank of England has noted that social spending, such as eating out, going to a concert or watching a football match, is a bigger driver of growth in the UK than in the US or the eurozone.

The chancellor told the BBC that the UK economy had performed worse than its EU counterparts because it was focused on services, hospitality and consumer spending.

“Those kinds of activities comprise a much larger share of our economy than they do for most of our European cousins,” he said.

The first official GDP numbers for this period show more than a fifth of the value of the economy lost since the beginning of the year, mainly driven by the severe shutdown in April.

The sheer extent and speed of the contraction, though not surprising, reflects an economic hit that has affected every High Street and town and city in the country.

The economy is now growing again, but not all the lights that were dimmed in the spring to protect public health will be turned back on.