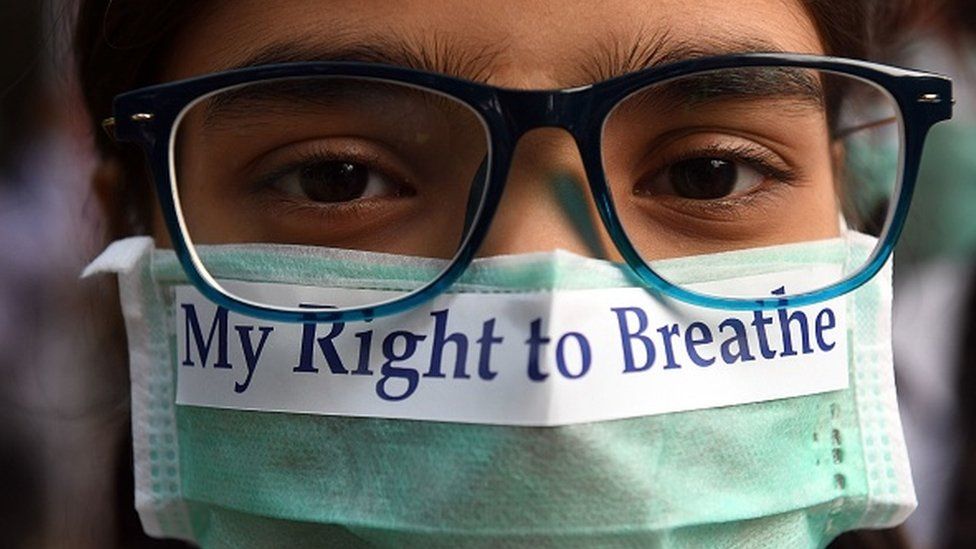

Pollution in India’s capital Delhi has made global headlines in recent years, but it’s not a new problem. For around four decades, the country’s top court has actively discussed the issue, sometimes passing orders that have significantly reshaped life in Delhi.

Its latest intervention came in early November, when the Supreme Court called for “immediate action” after air quality in the capital deteriorated to alarming levels.

The court heard arguments on measures implemented by the Delhi government to tackle the situation, from reducing stubble burning in the neighbouring states of Punjab and Haryana, to a proposal to allow motor vehicles only on alternate days, depending on whether the last number on their licence plates was odd or even.

The court left the decision of formulating these policies to the government – but last week, it pulled up authorities for not following its instructions to allocate funds for a rapid rail system, calling it a “gross breach of assurances”. The project aims to connect Delhi with its neighbouring cities through high-speed rail corridors to reduce vehicular pollution.

The top court also accused the Punjab state government of not doing enough to stop stubble burning and said that farmers in the state were being vilified due to its poor management of the problem.

The Supreme Court has often taken the lead in reforms to clean up Delhi’s air – some of its orders include rules on the kind of vehicles that should run in the city; the relocation of thousands of smoke-spewing factories; and the sealing of businesses to reduce emissions. It has also been lauded for making the government act, even when it was unwilling.

But critics have questioned the efficacy of the court’s decisions and accuse it of wading into executive action often. Some have also pointed out that despite reforms, pollution in the capital has only worsened over the past 40 years.

Shyam Divan, a senior lawyer, has recently wrote that India’s top court plays the role of a “policymaker, lawmaker, public educator and super administrator” all at once.

“In the US, they have the Congress, the Federal Environment Protection Agency and bags of money to protect the natural environment. Here, we have our Supreme Court,” he said.

However, the court’s defenders view it as a protector and a forum where problems can be solved collaboratively.

The top court first began hearing cases on Delhi pollution in 1984, when environmentalist MC Mehta filed a clutch of pleas on three main issues: rising vehicular pollution in Delhi, the impact of pollution on the iconic Taj Mahal, and the pollution of the rivers Ganga and Yamuna.

These pleas are still pending but the court has continued to add newer issues to these petitions – last year, the court clubbed together a plea on Delhi’s smog problem with an ongoing case on vehicular pollution.

Sometimes, the measures taken by the court have also been drastic.

In 1998, it ordered that the entire fleet of public transport vehicles which ran on diesel – estimated to be around 100,000 – switch to compressed natural gas, or CNG, by 2001.

Even though the government opposed the move, fines from the court and the fear of being held in contempt, ensured that the rule was followed.

In its order, the court has also waded into smaller details such as what type of vehicles should ply in Delhi – for instance, it froze the licences of tuk-tuk drivers for more than a decade.

The measures paid dividends, but only briefly. Studies have shown that the shift to CNG did help clean up Delhi’s air. However, experts say that these gains have been negated by the increase in the number of private vehicles in the city.

In his book Courting The People, lawyer Anuj Bhuwania, wrote that the order also adversely affected the lives of millions of workers employed in the public transport sector such as the tuk-tuk drivers, who never got the chance to present their side in court.

He says that the public interest litigation system in India, which was once considered one of the “most powerful weapons” to bring about societal change, has been taken over by a handful of lawyers and litigants who push for reforms while ignoring the interests of poor workers.

“At this point, if they [the court] washed their hands off it, we may not be worse off because they’ve done so much damage,” Mr Bhuwania told the BBC.

But some judges believe that the court’s intervention is necessary and has often been successful.

PN Bhagwati, a former chief justice who heard the pollution cases and was instrumental in expanding the court’s role into policy-making, once said that “judicial activism” was “inevitable”.

Another former chief justice, KG Balakrishnan said that although the court’s decisions have caused inconvenience to many, the initial success of the CNG order showed that the judges were willing to take “unpopular decisions” to clean up the environment.

Some legal experts, however, say that while the court has been clear-eyed in its aim to clean up the city’s air, some of its decisions have been questionable.

In November 2019, the court directed the federal government to install smog towers, which work like large-scale air purifiers, in the capital. At the time, several experts told the BBC that there wasn’t enough scientific evidence to prove that these towers would curb air pollution. Four years later, the capital’s pollution control board also concluded that the towers had been ineffective.

However, not everyone is of the opinion that the Supreme Court has made matters worse.

Environment lawyer Shibani Ghosh says that some of the court’s interventions have had a positive impact on the ground.

But when it comes to enforcing new laws and enacting policies, it “has to allow the government to take the lead,” she added.

Ritwick Dutta, an expert in environmental law, says that lower courts or specialised tribunals could play an important role in enforcing the existing environmental laws.

India has at least a dozen other laws, aiming to protect forests, wildlife, water and noise pollution for more than four decades.

“Even the Supreme Court, which has taken the lead in Delhi, listens to the case only when pollution is at its peak in the city”, Mr Dutta said.

“But the moment the air quality improves, the cases are once again put on the backburner.”