Chinese researchers have cloned the first rhesus monkey, a species which is widely used in medical research because its physiology is similar to humans.

They say they could speed up drug testing, as genetically identical animals give like-for-like results, providing greater certainty in trials.

Previous attempts to clone a rhesus have either not led to births or the offspring have died a few hours later.

One animal welfare group has said it is “deeply concerned” by the development.

In mammals, sexual reproduction leads to offspring made up of a mixture of genes from their father and mother. In cloning, techniques are used to create a genetically identical copy of a single animal.

The most famous cloned animal, Dolly the sheep, was created in 1996. Scientists reprogrammed a cell from another sheep to turn them into embryos which are building block cells that can grow into any part of an organism. These embryos were then implanted into Dolly’s surrogate mother.

Writing in the journal Nature communications, the researchers say they have essentially done the same thing but with a rhesus monkey. They say that the animal has remained healthy for more than two years, indicating the cloning process was successful.

Dr Falong Lu of the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences told BBC News that ”everyone was beaming with happiness” at the successful outcome.

But a spokesperson for the UK’s Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) said that the organisation believed that the animal suffering caused outweighed any immediate benefit to human patients.

Rhesus monkeys are found in the wild in Asia, with populations in Afghanistan through India, Thailand, Vietnam and China. They are used in experiments to study infection and immunity.

The first macaque monkeys were cloned in 2018, but rhesus monkeys are preferred for medical researchers, because of their genetic similarity to humans.

Image caption,

The problem with reprogramming adult cells to become embryonic is that in most attempts, mistakes are made in the reprogramming, and very few end up becoming born and fewer still are born healthy – between 1 and 3% in most mammals. And it has proved harder still with rhesus monkeys, with no births until the research team succeeded two years ago.

They discovered that in failed rhesus attempts, the placentas, which provide oxygen and nutrients to the growing foetus, were not reprogrammed properly by the cloning process and so did not develop normally.

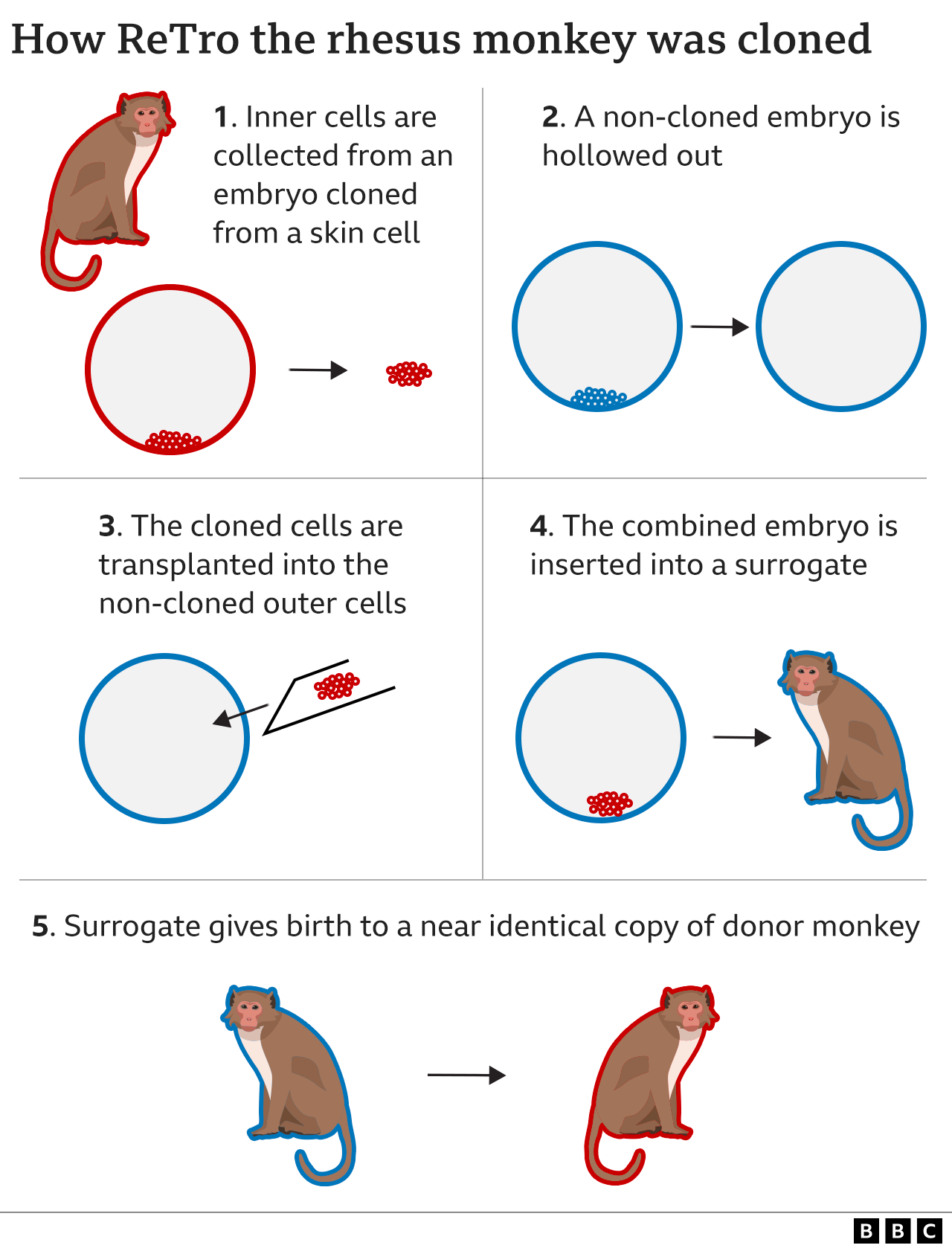

The researchers got around the problem by not using the part of the cloned embryo that goes on to develop into the placenta – the outer part. As the graphic below shows, they removed the inner cells – which develop into the body of the animal and inserted them into a non-cloned outer embryo – which they hoped would develop into a normal placenta.

The researchers used 113 embryos, 11 of which were implanted and achieved two pregnancies and one live birth.

They named the monkey “ReTro”, after the scientific method, called “trophoblast replacemement”, used to produce the animal.

The RSPCA said it had grave misgivings about the research.

“There is no immediate application for this study. We are expected to assume that human patients will benefit from these experiments, but any real-life applications would be years away and it is likely that more animal ‘models’ will be necessary in developing these technologies,” a spokesperson said.

“The RSPCA is deeply concerned about the very high numbers of animals who experience suffering and distress in these experiments and the very low success rate. Primates are intelligent and sentient animals, not just research tools”.

Prof Robin Lovell-Badge, of the Francis Crick institute in London, who strongly supports animal research when the benefits to patients outweigh the suffering to animals, has similar concerns.

“Having animals of the same genetic make-up will reduce a source of variation in experiments. But you have to ask if it is really worth it.

”The number of attempts they had is enormous. They have had to use many embryos and implant them into many surrogate mothers to get one live born animal.”

Prof Lovell-Badge also has concerns that the scientists have produced only one live birth.

”You cannot make any conclusions about the success rate of this technique when you have one birth. It’s nonsense to ever propose you can. You need at least two, but preferably more.”

In response, Dr Falong Lu told BBC News that the team’s aim is to obtain more cloned monkeys while reducing the number of embryos used. He added that all ethical approvals had been obtained for the research.

“All animal procedures in our research adhered to the guidelines set by the Animal Use and Care Committees at the Shanghai Institute of Biological Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), and the Institute of Neuroscience, CAS Center for Excellence in Brain Science and Intelligence Technology. The protocol has been approved by the Animal Use and Care Committee of the CAS Center for Excellence in Brain Science and Intelligence Technology”.