Why ethnicity may no longer decide Kenya’s elections

As Kenya gears up for a general election on 9 August, the BBC’s Dickens Olewe writes that ethnic divisions have long bedevilled the nation’s politics – although there are signs this may now be changing.

On a chilly morning on 20 January 1994 I walked into the classroom to taunts.

I don’t remember much of what was said but one stayed with me.

“Your god is dead,” a classmate shouted.

Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, Kenya’s first vice-president who later became a doyen of opposition politics, had died.

Despite only being in primary school, we were all well versed about our country’s ethnic-based politics, so my classmate understood what a huge political loss the death was to the Luo community.

Ethnic taunting was not uncommon in school playgrounds and even in classrooms, where some teachers used stereotypes to praise or criticise pupils’ behaviour.

This was, and still is, mostly seen as harmless humour, but sometimes it turns negative.

Another striking moment came eight years later when a confident four-year-old girl walked up to me on my first day volunteering at a charity supporting poor families in Nairobi, and asked a pointed question in Swahili: “Wewe ni kabila gani?” – in English: “What’s your tribe?

She wasn’t pleased with my mealy-mouthed reply, especially because I later learnt that my ethnicity had been part of an intense debate with her peers – their interest likely inspired by the heady political conversations of the time.

The childhood curiosity was cute, but I felt uncomfortable. Social mores had taught me to abhor such questions, especially when put so bluntly. I also worried what my answer would mean to her.

Kenya’s politics has been dominated by competition among its more than 40 ethnic groups, but it’s especially intense among the larger ones.

Politicians often exploit historic grudges and cultural differences to incite violence so they can win elections.

This cynical strategy is as old as time and its tragic consequences continue to be experienced the world over.

In Kenya, ethnic identity has been used to grant privileges – sometimes it’s the only qualification considered for a job, a vote in the election, or even in accessing mundane favours from someone in a position of authority.

It has been weaponised to humiliate and frustrate others – a situation that breeds a siege mentality in those bearing the brunt, and a sense of entitlement among those benefiting from it.

Politics therefore becomes a zero-sum game, at the expense of addressing pressing issues that could better people’s lives.

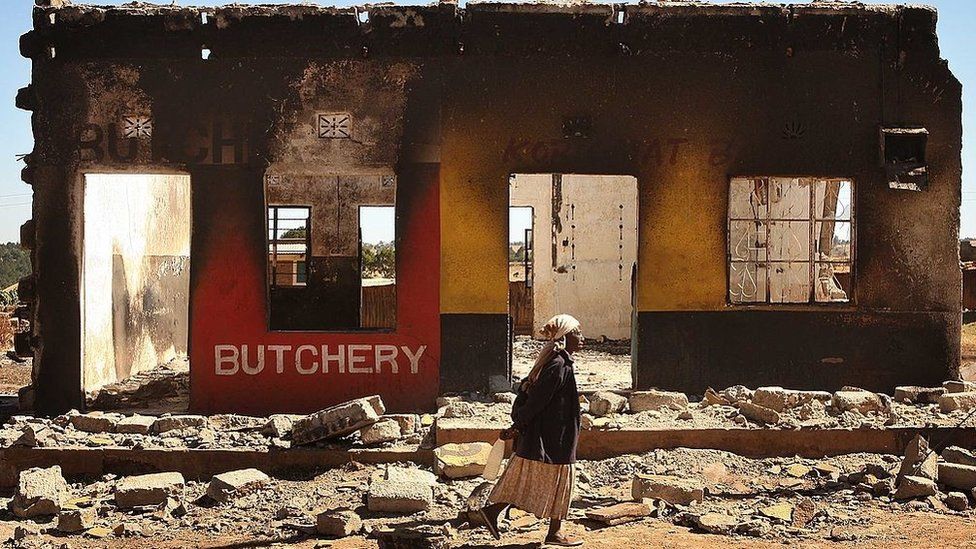

Kenya saw horrific ethnic-based violence after the disputed 2007 election, when more than 1,500 people were killed, hundreds more were injured and 600,000 were forced to flee their homes.

The violence was probably Kenya’s lowest moment since independence.

A nation that had largely been peaceful, and had offered sanctuary to hundreds of thousands of refugees from across the continent, had turned on itself. The trauma of that time still lingers.

During this election, some families plan to temporarily move to areas where their ethnic group is the majority to avoid being victimised, while mixed-ethnicity couples often face the biggest challenge as they calculate where it would be safest.

“Kenya has a sad history of unresolved grievances, stretching 50 years, that often trigger violence, and politicians have become adept at creating fear between communities,” Sam Kona, a commissioner at the state’s National Cohesion and Integration Commission (NCIC), told the BBC.

“People are blind to the fact that this is just a contestation of power among the elite, and once it’s over, the elite get together whether they won or not,” he added.

Mr Kona said tensions among communities in the six counties which NCIC has labelled as potential hotspots in the upcoming election were because of “missed opportunities to reconcile”.

He pointed out that Kenya adopted a new constitution in 2010, creating 47 counties – with their own governors – to end a winner-takes-all mentality.

It promised that all counties would be treated equally, and would receive a fair share of the national budget to plan their own development to avoid the need for different groups to compete for resources.

“Unfortunately most Kenyans still see the presidency as the main source of power – a situation that causes tension,” Mr Kona said, adding that the NCIC had intensified efforts to promote peace in potential flashpoints.

Governance expert John Githongo had to flee the country in 2005 because he was considered a traitor by some members of his Kikuyu community after he exposed a massive corruption scandal in the administration of then-President Mwai Kibaki, a fellow Kikuyu.

He told the BBC ethnic mobilisation was less overt in this election campaign, largely because Deputy President William Ruto has shaped it as a contest between “dynastic families” and “hustlers”.

He lumps his main challenger, Raila Odinga, a veteran opposition politician and the son of Kenya’s first vice-president, in the former category, along with President Uhuru Kenyatta,the son of the first president. While he portrays himself as the champion of “hustlers” – a reference to poor Kenyans.

Mr Odinga has criticised the framing as an attempt to divide Kenyans along class lines, and has focussed his campaign on a message of unity.

But in a significant change from previous campaigns, the two front-runners have mostly traded barbs over their economic and social policies.

This is not surprising as the election comes in the midst of a cost-of-living crisis, worsened by high unemployment and a huge national debt.

In a major intervention just weeks before the election, President Kenyatta’s government announced that maize flour – used to make the country’s staple food, ugali – will be subsidised to bring down its price.

Mr Ruto saw the timing as an attempt to bolster Mr Odinga’s chances in the election.

Mr Kenyatta is backing Mr Odinga in the election, even though Mr Ruto is his deputy.

It is a sign of the changing nature of alliances within Kenya’s ethnically-influenced political elite. In 2007 Mr Odinga and Mr Ruto teamed up against Mr Kibaki, who Mr Kenyatta was supporting.

Some of the worst violence after the 2007 election pitted members of Mr Ruto’s Kalenjin community against Kikuyus like Mr Kenyatta, with people killed on the basis of their ethnic background.

However, in 2013 and 2017 Mr Kenyatta and Mr Ruto joined forces against Mr Odinga, a Luo, only for Mr Kenyatta to now throw his weight behind Mr Odinga.

“Kenyans have grown tired of all the byzantine alliances they’ve been seeing among the elite,” said Murithi Mutiga, Africa programme director at the International Crisis Group.

“I think this has made Kenyans much more indifferent, much less inflamed, much more likely to see that the elite are basically just playing their own game,” he added.

Mr Githongo said that said that while ethnic tensions rise during elections, “people are marrying each other immediately afterwards”.

“Among the youth it’s much less of a problem but the politicians mobilise along ethnic lines,” he added.