Why Donna Summer was “one of the original rock stars”

Every musician has a heyday period with which they are most closely associated. But for Donna Summer, this imperial phase defines her more than most. Thanks to a string of indelible hits in the late 1970s – including Love to Love You Baby, I Feel Love, Last Dance, Bad Girls and On the Radio – she is invariably described as the “Queen of Disco”. It’s a title Summer deserves, because she definitely became the pre-eminent artist of the disco era – but it’s one that also feels a bit reductive.

Clearly, there’s more to Summer’s life and career than her purple patch alone. “Donna Summer is iconic because of her authenticity as a performer, look and pioneering style,” says Jillian Hervey of alt-R&B duo Lion Babe. “Her sound transformed music and her freedom of expression has inspired female artists from the bottom up.

Hervey isn’t exaggerating in the slightest. When Summer died of lung cancer on 17 May 2012, artists including Kylie Minogue, Solange and Katy B lined up to say she had inspired them.

Her music has been referenced by everyone from Beyoncé, who interpolated Love to Love You Baby on her 2003 hit Naughty Girl, to pop-rock band Texas, who sampled Summer’s Love’s Unkind on this year’s single Mr Haze.

Singer-songwriter Jessie Ware hailed Summer as a major influence on her acclaimed 2020 album What’s Your Pleasure?, saying: “She just had this power and this femininity and flirtation I was so obsessed with. And I kind of wanted to have all that on this record.” The singer’s music remains such a touchstone that the title of her 1994 greatest hits album, Endless Summer, is tough to argue with.

“I Feel Love is undoubtedly one of the most influential records of all time,” says Luke Howard of globally renowned club collective Horse Meat Disco. “But, even if you take it away from Summer’s back catalogue, she’s still one of the most successful solo female recording artists of all time.” Though Summer’s career peaked commercially during the late 1970s as disco conquered the mainstream, she continued to score hits after the genre fell out of favour. Its commercial decline was hastened by the Disco Sucks movement led by mainly white rock fans who felt threatened by the success of a genre rooted in the black and queer underground. Fuelled by latent racism and homophobia, it reached a toxic apex on 12 July 1979, the infamous Disco Demolition Night, when thousands congregated in a Chicago baseball field to detonate crates of disco records in a grim publicity stunt.

Given how synonymous Summer had become with disco, it is impressive that she continued to score hits through the subsequent decade – most notably 1983’s new wave gem She Works Hard for the Money and 1989’s spangly pop banger This Time I Know It’s for Real. Nearly a decade after her death, even relatively obscure Summer songs are catnip for contemporary DJ-producers: the likes of Junior Vasquez, Oliver Nelson and Ladies On Mars have just queued up to remix tracks from I’m a Rainbow, a so-called “lost” album that her record company shelved in 1981, because they felt its disco sound was passé, and wanted Summer to transition to a more R&B-oriented style.

Titled I’m a Rainbow: Recovered and Recoloured, this new release highlights the timelessness of Summer’s voice. Hearing her glide over Ladies On Mars’ turbo-charged beat on his thumping update of Leave Me Alone is thrilling, especially when she delivers the empowering pay-off line: “I’ll never belong to you or any other man”. The original album’s co-producer Pete Bellotte blames its fate on Summer’s then-label boss, David Geffen. “I never understood why he signed her in the first place because he hated disco music,” he says. “He was a fantastic guy, but in my opinion he was totally the wrong person for her.” Still, Bellotte says he didn’t sulk for too long at the time because a track from the album, Romeo, later earned a “nice sum of money” for all involved when it appeared on 1983’s hugely successful Flashdance movie soundtrack.

More than the Queen of Disco

Writer and podcaster Ira Madison III, who a few years ago compiled a definitive guide to Summer’s music for VICE, points out that Summer’s discography also includes rock anthems such as the strutting 1979 chart-topper Hot Stuff and “some incredible gems of R&B music”. Indeed, one of her most gleaming R&B diamonds, 1982’s Love Is in Control (Finger on the Trigger), was produced by Quincy Jones the same year he worked on Michael Jackson’s Thriller: a sure sign of Summer’s cachet at the time. “Of course it’s easy to pigeonhole black artists into one genre, and while she wasn’t as influential in her other genre forays outside of disco, this work is very representative of her incredible range as an artist,” says Madison III.

She had this incredible depth of tone as well as the range. In my opinion, she’s the greatest singer I’ve ever worked with ¬– Pete Bellotte

What’s more, Summer didn’t just define disco during her imperial phase, but transcended its confines. Howard says that while “dance music was and still is to a certain extent a club-based genre”, Summer “took it out of the clubs and right to the top of the charts”. In 1978 and 1979 alone, she dominated the Billboard Hot 100 with eight top-five singles. Howard also points out that during this period, Summer was making double albums, something “unheard of for a dance artist” that underlined her status as a genre-smashing superstar. “It put dance music on a par with rock music, which was an album-based genre at the time,” he adds. In a way, Summer beat the rock guys at their own game by becoming, in 1979, the first artist to send three consecutive double albums to the top of the Billboard 200. Hervey says Summer should be thought of as “one of the original rock stars”.

By the time she broke through in the mid-1970s, Summer was already an experienced performer. Born and raised in Boston, the daughter of a butcher and a teacher, she cut her teeth in school musicals before moving to New York City in 1967 to join a blues band called Crow. The following year, she relocated to Munich after landing a role in the city’s production of zeitgeist-grabbing rock musical Hair. Six years later, while working as a backing singer in the same city, she met songwriter-producers Bellotte and Giorgio Moroder and began an incredibly prolific seven-year collaboration that yielded most of her biggest hits.

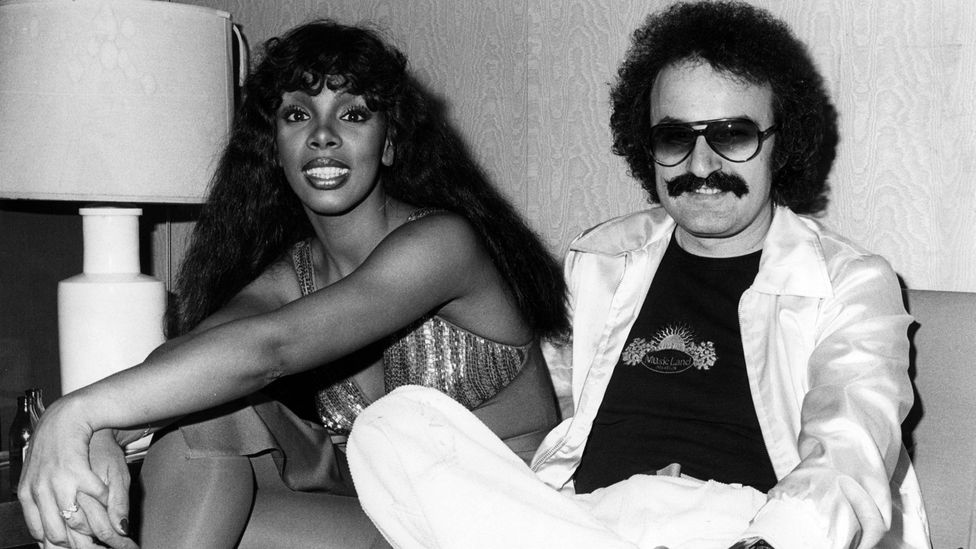

Donna Summer’s collaboration with songwriter-producers Giorgio Moroder (pictured, right) and Pete Bellotte yielded most of her biggest hits (Credit: Getty Images)

Bellotte, who says the trio were so creatively in sync that they never once had an argument, is still in awe of Summer’s voice more than 45 years later. “She had this incredible depth of tone as well as the range,” he says. “In my opinion, she’s the greatest singer I’ve ever worked with.” In fact, Bellotte says Summer was so naturally gifted that she recorded nearly every song in one take; only her chart-topping 1978 cover of Jimmy Webb’s MacArthur Park, a record that “really proved her prowess as a vocalist”, required a second attempt. Howard describes Summer as “a producer’s singer” because she “used her voice like an instrument”. “She had power, clarity [and] the ability to sustain a note without the tricks of vibrato or melisma that are so often used by contemporary singers,” he adds. For him, Summer’s fabulously melodramatic duet with Barbra Streisand, 1979’s No More Tears (Enough Is Enough), works so well because their “similar singing styles” are “a match made in heaven”.

Bellotte says modestly that Summer “really made” the songs he and Moroder produced for her, calling her “an alchemist who could turn base metal into gold”. She demonstrated her ability to elevate already visionary source material when they came to record 1977’s I Feel Love, a game-changing electronic dance record that David Bowie called “the sound of the future” when he first heard it. “She could have sung it in her regular voice, but she went straight into her head voice,” Bellotte recalls. “And that made it magical straight away, because she took the song so far away from the machine-driving beat. She really floated above it.” Hervey says this kind of singing has influenced her work with Lion Babe, praising Summer’s ability to “bring her dreamy and ethereal sensuality to hard-hitting beats”.

Her power as a songwriter

Summer also proved her songwriting chops in an era when few female pop artists were encouraged to do so. Though she had no co-writing credits on her 1974 debut album Lady of the Night, produced by Bellotte and released only in the Netherlands, she was credited alongside Bellotte and Moroder on her iconic 1975 breakthrough single Love You to Love You Baby. From this point on, the trio formed a fruitful songwriting partnership that yielded further hits including I Feel Love, Love’s Unkind and I Love You. By 1979’s Bad Girls album – widely considered Summer’s best – she was confident enough to write several songs unaided. Dim All the Lights, a slinky disco ballad that she wrote alone and originally intended to give to Rod Stewart, peaked at number two on the Billboard Hot 100.

Nearly 10 years after her death, Summer’s music continues to fill dance floors and touch people’s lives – often at the same time

At its best, Summer’s songwriting was richly empathetic. She was reportedly inspired to write Bad Girls’ iconic title track after one of her assistants was mistaken by a police officer for a street-walking sex worker. This led Summer to imagine the lives of women who really did sell sex for a living. “Now, don’t you ask yourself, ‘Who they are?'” she sings on the pre-chorus. “Like everybody else, they wanna be a star.” Cleverly, Summer carried the theme into the album’s cover art, which includes an image of her posing under a red street light while a cop keeps an eye on her. Because this scene is in the background, behind a larger head-and-shoulders shot of the singer, it’s relatively subtle and less provocative than it might have been. Still, it appears to foreshadow the more determined envelope-pushing when it comes to sex and sexuality that Madonna went on to perfect in the 1980s. It’s worth noting, too, that Summer’s breakthrough single Love to Love You Baby rode a tide of Madonna-like controversy into the charts back in 1975. Because her purring vocal performance was deemed by some to be overly sexually suggestive, the song was banned by the BBC and several other broadcasters across the world. When Summer died in 2012, Madonna paid tribute by tweeting “rest in peace” with a link to Future Lovers, her 2005 song written in homage to Summer’s I Feel Love.

Summer displayed a similar ability to channel someone else’s lived experience with 1983’s She Works Hard for the Money. During a meal at a fancy Hollywood restaurant, she spotted an exhausted bathroom attendant sleeping on the job and decided to write a song about it. Accompanied by an evocative video that got heavy rotation on MTV at a time when few black artists were being championed by the channel, it’s resonated with breadwinning women ever since.

After 1989’s Another Place and Time album, a collaboration with the then-red-hot Stock Aitken Waterman songwriting team that spawned three UK top 20 singles, Summer recorded relatively infrequently. By this point, she was in her early 40s, a challenging age for a woman navigating the notoriously sexist music industry. Summer’s reputation had also been dented by persistent rumours of homophobia that, as an artist with a large gay fanbase, she never quite managed to shake off. In 1983, it was reported by the Village Voice that the profoundly religious singer had called the new disease Aids “a punishment from God” – something she always strenuously denied. “I still don’t believe she could ever have said anything like that because when I was working with her, most of her friends were gay,” Bellotte says today.

Bellotte also suggests that Summer may have been “mismanaged” during her later career. “I never understood why she didn’t get more involved in major film soundtracks,” he adds. After all, Summer certainly had proved herself on this front: she scored a UK top five hit in 1977 with Down Deep Inside, the theme tune for disaster movie The Deep that she co-wrote with Bond composer John Barry. Still, it would be pedantic to question her glittering career too much by wondering what might have been. Nearly 10 years after her death, Summer’s music continues to fill dance floors and touch people’s lives – often at the same time. Howard says Last Dance is the “perfect end of the night record” at any Horse Meat Disco event, but adds: “I couldn’t play it for many years because it was played on loop at a friend’s funeral in the ’90s as we were leaving the service. After that, it was just too upsetting to hear.” In a way, this deeply poignant story neatly sums up Donna Summer’s appeal: she was the Queen of Disco, but also so much more.