What’s in a pen name? A whole heap of patriarchal oppression, if we’re to believe a recent publishing endeavour. To celebrate 25 years of the Women’s Prize for Fiction, one of its sponsors Baileys ran the Reclaim Her Name campaign: 25 works by women who published under a male name were relaunched with their ‘real’ names restored. The tag line read: “Finally giving female writers the credit they deserve”.

It was a nice idea, and anything that drives attention to a broader selection of female writers from history is welcome. But #ReclaimHerName quickly provoked an outcry online, horrified at how a feminist project had, in fact, erased deliberate choices made by the women it was supposedly uplifting.

Because a pen name is a complicated thing: while it can be used to circumnavigate gendered expectations, it can also be a way of maintaining anonymity, crafting a public persona or alter ego, reflecting a lived queer identity, and aligning with – or avoiding – expectations of racial heritage.

The campaign did itself no favours by making numerous clumsy errors and jaw-dropping choices. They erroneously illustrated Frances Rollin Whipper’s biography of abolitionist Martin R Delany with an image of Frederick Douglass.

The attribution of a story to the Chinese-English writer Edith Maude Eaton was criticised by the only academic to even suggest she might have written it, because it was still only speculation – plus they ‘restored’ Eaton’s birth name rather than the female Cantonese name she very purposefully chose to publish under: Sui Sin Far. NK Jemisin, who uses initials to make a distinction between her academic work and fiction – nothing to do with gender – was asked to donate a story for free. Because not paying women is excellent feminism. And despite the project being called Reclaim Her Name, they didn’t even manage that: the poet Katharine Bradley was spelt as Katherine.

The most successful female author of this century, JK Rowling, adopted a gender-neutral name to ensure Harry Potter appealed to boy readers

But behind the outrage was a more general weariness at the myths such a project upholds: that historically, women have struggled to get books published, that they could only achieve success by hiding behind a masculine name, and that revealing their ‘real’ names brings them gloriously into the light.

There are cases where this may be true – at different times, in different countries, and for women of different races, and different class backgrounds, sexism has absolutely contributed to a struggle to be heard. Even the most successful female author of this century, JK Rowling, adopted a gender-neutral name to ensure Harry Potter appealed to boy readers, before taking on the pseudonym Robert Galbraith in order to anonymously write crime fiction. But even that single contemporary example cracks open how thorny this issue is: Rowling’s choices were not just about sexism, but also about a desire for anonymity, and the crafting of a new identity.

And that is almost always the case – it’s rarely so simple as just the bad sexism keeping a good woman down. Perversely, assuming it is so actually perpetuates vague, muddled notions that, historically, only a few women ever managed to break through, and did so by pretending to be men – think George Eliot, the Brontës.

Our education system is partly to blame: the traditional canon, created by men, has tended to focus on men since the novel’s inception in the 18th Century. “Actually, you have a load of women writers being incredibly important in the rise of the novel,” points out Dr Sam Hirst, an associate lecturer and host of free online Romancing the Gothic classes. “By reproducing these narratives – that women couldn’t publish unless they had a male pseudonym – you are completely erasing the existence of all of these other women. You’re reinforcing this incredibly patriarchal and misogynist view of the canon.”

Women published anonymously, pseudonymously and under their own names in the 18th and 19th Centuries; being written ‘by a lady’ actually became a selling point, to the extent that male authors would adopt it. According to research by academic James Raven, almost a third of novels published in 1785, for instance, claimed to be ‘by a lady’. While such anonymity means it’s hard to know exactly how many writers were really men, it’s believed that some deliberately opted for ‘by a lady’ as a sales ploy: female authorship helped indicate that the subject matter would be suitable for feminine readers, and it was women who made up most of the novel-buying market.

‘Perpetuating lazy myths’

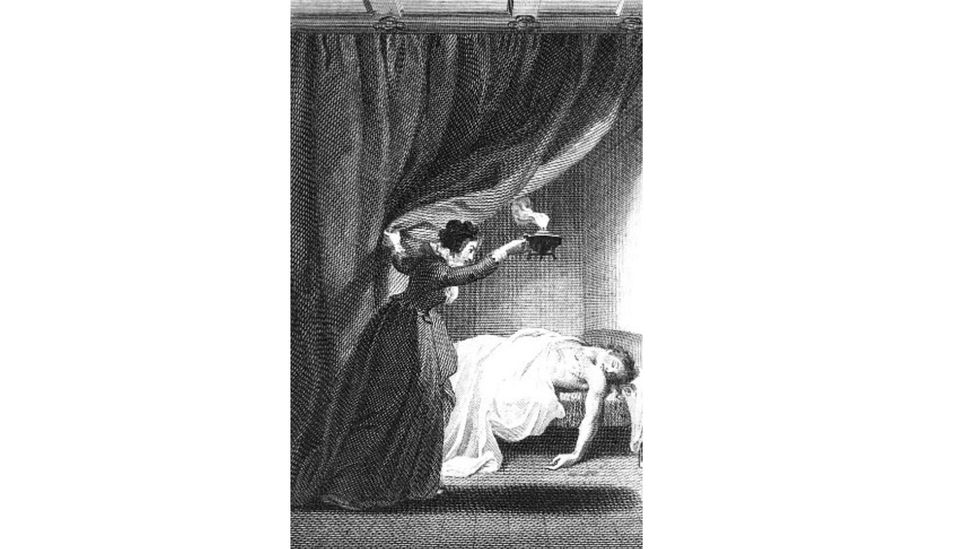

The ignoring of women’s success in this era is bound up with issues of genre. In the late 18th and early 19th Centuries, the Gothic novel was wildly popular, and also largely associated with women. Female writers dominated the industry, with Ann Radcliffe achieving a record-breaking advance with The Mysteries of Udolpho, reprinted multiple times. She was one of innumerable ‘scribbling women’ making money this way – see also Mary Robinson, Clara Reeve, Charlotte Dacre, Eliza Parsons, Charlotte Smith, and of course, Mary Shelley.

There’s certainly sexism afoot here: the novel, whether written by men or women, was often seen as frivolous – and the Gothic novel, in particular, was derided as excessive and distracting to women readers. The genre’s association with women both produced this dismissal, and was a product of this dismissal, Hirst suggests. Such contemporary sneering carried through in the creation of the canon: “One of the reasons we’ve talked about men as so central to the history of the novel is that the Gothic novels are totally ignored,” they add.

Since the 1970s, there have been huge efforts by academics and publishers to look again at female writers, from Eliza Haywood to Frances Burney to Margaret Oliphant – which is why perpetuating lazy myths that there weren’t women writing under their own names is so unhelpful, half a century on. Still, Hirst acknowledges that, moving forward in the 19th Century, there were female writers who sought to distance themselves from populist, ‘trashy’ novels by adopting male pseudonyms. It’s just that things continue to be inconveniently more nuanced that.

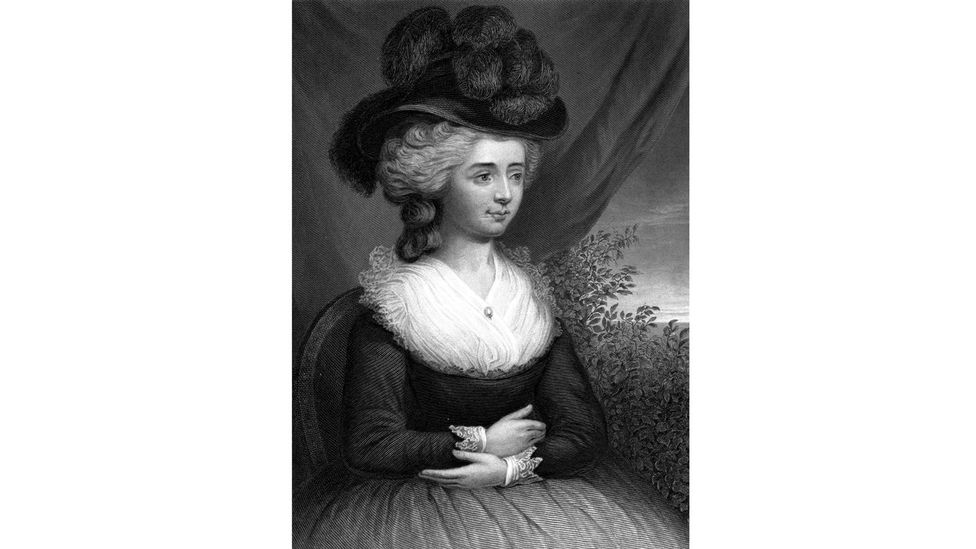

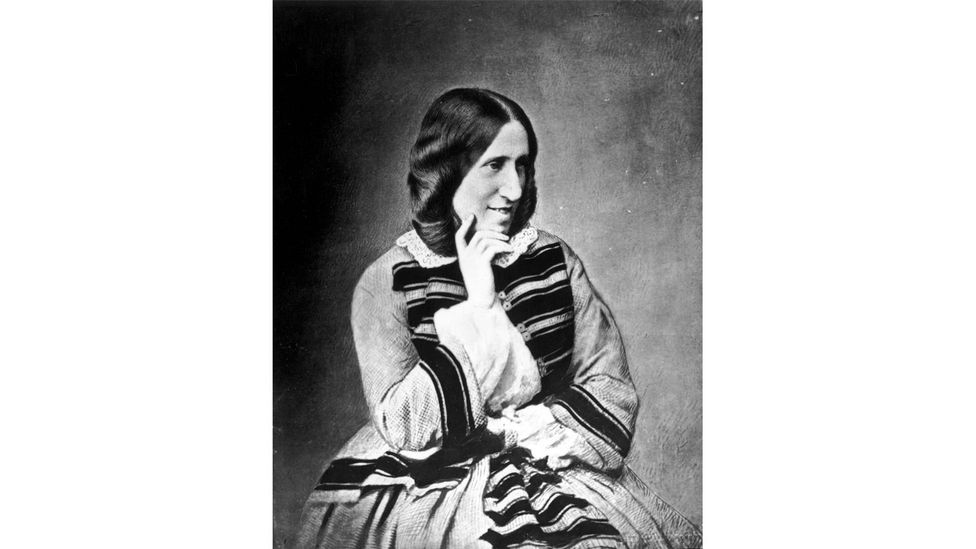

George Eliot is a name many would reach for as evidence of someone ‘forced’ to publish as a man to be taken seriously. But initially, suggests Rosemarie Bodenheimer, Eliot biographer and professor emerita of Boston College, she was seeking anonymity because of her unusual relationship status. In 1854, Eliot had eloped to Germany with George Henry Lewes, who was in an open marriage with another woman. Eliot adopted a pen name because she wanted her work to be judged without “the sexual scandal” of her status as a “fallen woman” attached.

But, Bodenheimer points out, there were also more prosaic reasons. Even Eliot worried that her writing wasn’t good enough – and a pseudonym has long been a face-saving mechanism. Plus, it was an accustomed habit: working as a journalist, her articles were often published anonymously or pseudonymously.

It’s also worth remembering that – as with many of the Reclaim Her Name authors – Eliot’s identity was soon public knowledge. Her debut novel, Adam Bede, was such a hit that she quite quickly had to scotch other people’s false authorship claims. Why stick with Eliot then? “The pseudonym was now the public brand name, as well as a deep part of her writer’s confidence,” suggests Bodenheimer.

George Eliot initially adopted a pen name because she wanted her work to be judged free from the scandal of her status as a ‘fallen woman’ (Credit: Getty Images)

Besides, what would she have changed it to? A problem for any scholar wishing to ‘restore’ an author’s name is that women’s names often change through marriage. In the case of Eliot, this is compounded by her own tinkering: she was christened Mary Anne Evans, and subsequently changed it to Mary Ann Evans (from 1837), Marian Evans (from 1851), Marian Evans Lewes (from 1854), Mary Ann Cross (1880). Each shift “signalled a new period of her life”, says Bodenheimer, suggesting that crafting her names held symbolic import for Eliot.

Republishing Middlemarch – written in 1871 – under the name Mary Ann Evans, therefore, ties her mature fiction to her youth. “I think she would have been rather horrified, actually,” says Bodenheimer. “‘Mary Ann’ strikes me as sending her back to a stifled girlhood, before she had any inkling that she could become a writer.”

Creating new identities

A host of other authors might be reluctant to be ‘sent back to girlhood’ for another reason: a masculine pen name may be intimately intertwined with a queer identity.

Take Vernon Lee, born Violet Paget, a writer of ghost stories, cultural criticism, and pacifist polemics. Openly lesbian – within her aestheticist circles at least – she had romantic relationships with writers A Mary F Robinson, Clementina ‘Kit’ Anstruther-Thomson, and Amy Levy.

Lee wrote in 1875 that her pseudonym “has the advantage of leaving it undecided whether the writer be a man or a woman,” Dr Ana Parejo Vadillo, reader in Victorian literature at Birkbeck, says: “that sense of being free from gender, free from sex, at a period in which those kinds of categories are very heavily fixed in the minds, was quite important for her.” Unlike those using a pseudonym to mask their identity, Lee used it to craft a new one: she went by Vernon Lee in all aspects of her life, rejecting gender binaries, and later experimenting with androgynous dress.

Names had possibilities and freedoms, space for invention – to create your authorship is an artistry – Dr Ana Parejo Vadillo

There is no pseudonym here, really, points out Vadillo: “Everybody knew that she was a woman – although she often was thought of as having a ‘masculine’ intellect.” Even her lovers called her Vernon, not Violet. “Using Violet Paget is really a way of reclaiming her by erasing queerness,” says Vadillo. Crafting ‘Vernon Lee’ was a creative act in and of itself, then, her authorial identity combined with her identity as a queer woman.

It is striking that Lee is not alone in this: in the late 19th and early 20th Century, we see several queer writers playing with abbreviating, changing, or neutralising their names: Radclyffe Hall, George Sand, Vita Sackville-West (who published just as ‘V’), HD, Colette.

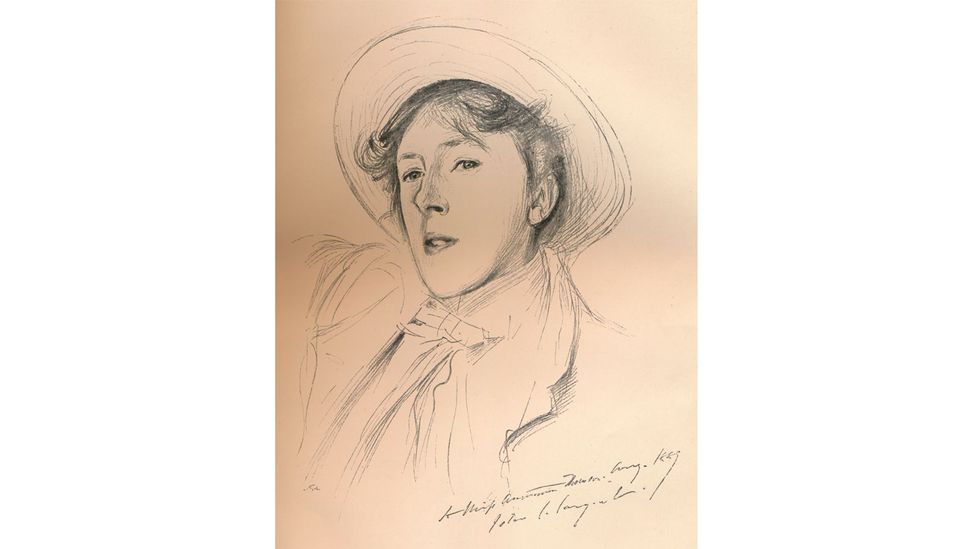

Another lesbian couple of the Victorian era – Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper, also aunt and niece – went further: they published their collaborative work under the name Michael Field. Once more, the boundaries between art and life proved porous.

“They really became Michael Field,” says Vadillo. “Their friends would write ‘Dear Michael’ [for Bradley] or ‘Dear Field’ [for Cooper], or ‘I would like to invite Michael Field to my party…’”

Making up this character may also have simply been more fun than narratives about downtrodden women allow for. The couple were constantly giving each other pet names – Bradley was the Simiorg, and the All-Wise-Fowl, while Cooper known as Puss, and later Henry. “Names had possibilities and freedoms, space for invention,” insists Vadillo. “To create your authorship is an artistry.”

The story goes that their writing was taken seriously, until the poet Robert Browning leaked the truth to the press. The reality is less neat: the dismissive reaction was “mostly against the collaborative nature of the relationship, and also the fact that they were aunt and niece,” says Vadillo. “There’s nothing quite like that in literary history.” Poetry was still in thrall to the notion of the individual, usually masculine, genius – collaborative intergenerational female verse was, frankly, a bit much.

Lesbian couple Edith Cooper (pictured) and Katharine Bradley published their work collaboratively under the name Michael Field (Credit: Alamy)

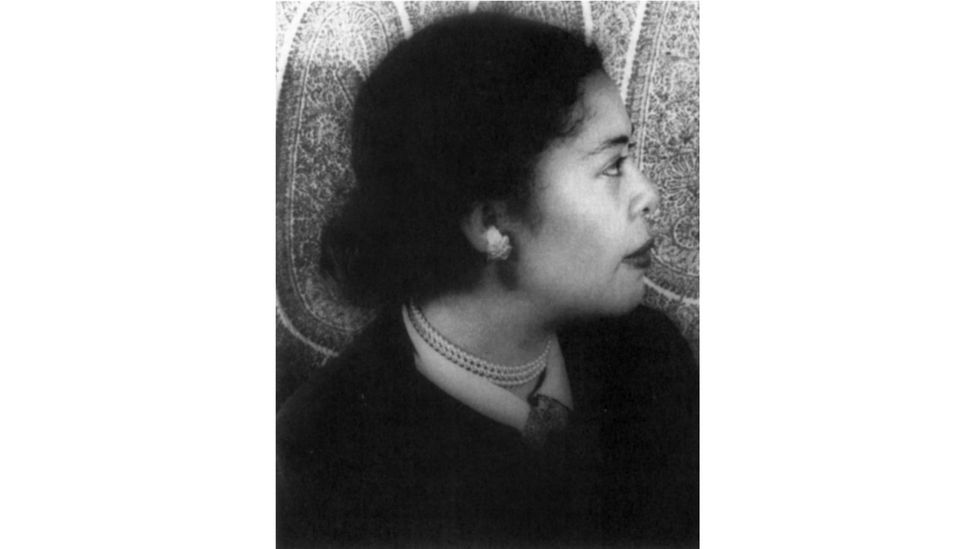

The choice of a pseudonym may also be influenced by an author’s race. The assumption might be that pseudonyms were necessary to help writers of colour pass as white, in order to get published – however, the example of Ann Petry, an African-American writer whose short story Marie of the Cabin Club was printed under the pseudonym Arnold Petri in 1939 (and is included in Reclaim Her Name), reveals a different story.

For starters, we once again see ordinary human bashfulness at play: “given her early life as a rather private person, she used the pseudonym ‘Arnold Petri’ to avoid the unwanted or excessive attention from friends and acquaintances,” explains Gene Jarrett, professor of English at NYU. But Petry became comfortable enough through publishing stories that, by the time of her 1946 debut novel The Street, she was able to ‘enjoy the fame’ of publishing under her real name. And what fame: The Street became a sensation, the first novel by an African-American woman to sell more than one million copies.

While it would be naïve to suggest that being a woman of colour did not bring its own considerable challenges for a writer in the 1940s, it didn’t necessarily harm their commercial prospects – indeed, Jarrett suggests that books being written by African-American authors “inspired readers to take seriously their literary depictions of race relations.”

African-American writer Ann Petry used the pseudonym ‘Arnold Petri’ to avoid excessive attention for the success of her work – perhaps through bashfulness (Credit: Alamy)

But he also points out that using pseudonyms or publishing anonymously around this time was “more frequent than one may realise” for black men and women in the US. “African-American writers renowned, in their own names, for bestselling or critically acclaimed literature – ranging from Paul Laurence Dunbar and Pauline Hopkins in the late 19th Century to James Weldon Johnson and Langston Hughes in the early-to mid-20th – wrote stories [using pseudonyms],” Jarrett explains. It’s just that it was less about concealing an identity, and more about supplementing it.

Once again, genre is the key here. Writers used their real name for ‘serious’ literature, expected to authentically reflect the African-American experience and explore racism – both opening up opportunities while also narrowly prescribing the kind of work they could produce. So they often adopted pen names to make a buck writing popular fiction. Marie of the Cabin Club is a good example: a fervid romance-thriller, it was published in a mass-market newspaper, complete with illustrations.

This is a distinction we still see today – although, ironically, when it comes to genre fiction, a recent trend is for male writers to publish under gender-neutral pseudonyms. Or at least initials that allow readers to make their own assumptions: see crime and thriller-writers such as SK Tremayne (Sean Thomas), Riley Sager (Todd Ritter), SJ Watson (Steve Watson), JP Delaney (Tony Strong). Women today are thought to represent up to 80 per cent of the market for buying all books – a statistic that holds, even in crime – and having a gender-neutral name is thought to be more appealing.

Female writers may have historically had many and fantastically varied reasons for adopting male pseudonyms – but these days, your book being assumed to have been written ‘by a lady’ may, as with the Gothic novel, actually help. Just don’t go claiming that’s a historical first.