While Food Shortage Looms, A Desperate Agric Minister Fights A Narrative War

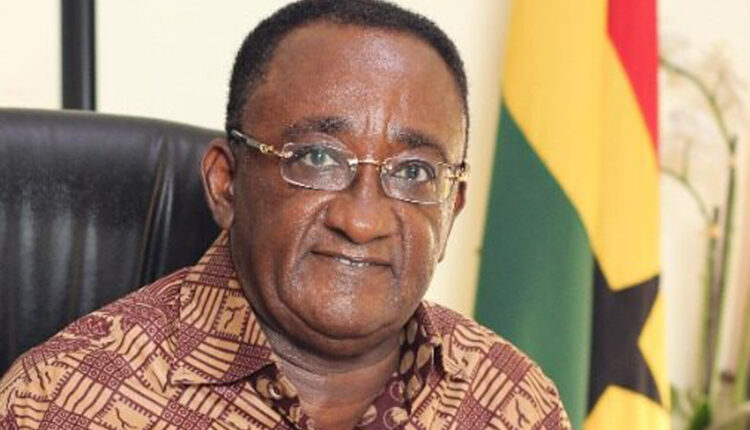

When the Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MOFA), under the leadership of Dr Owusu Afriyie Akoto, is usually assessed, the weight of evidence that is marshalled leaves some room to be desired.

It has to be said that the supposed inadequacy is what Dr Akoto constantly claims.

Whether the issue is about food security or the business of keeping farmers afloat, there is a lack of statistical data according to Dr Akoto. The substantive minister himself realised this when he pushed back in September against fears that Ghana was facing a food shortage.

“Not shortage. I wouldn’t call it shortage. Shortage of what? You have to define what is shortage…Shortage is where human beings in spite of what money you carry, can’t get food to buy. That is a shortage. If you say shortage, all these countries are now coming to Ghana to pick their grains. Why? Because there is a shortage in their countries that is why they had to go elsewhere,” Dr Akoto argued in a TV interview on September 22, 2021.

Did Dr Akoto use his TV interviewer’s lack of evidence against him in the discussion? Was the minister simply stating facts per Ghana’s food security?

The answers to both questions are certainly linked. Both of them cannot be true.

However, consider this. Exactly a week before Dr Akoto would claim that Ghana was not facing a food shortage, his deputy, Yaw Frimpong Addo, was interviewed by the same media house – Multimedia -, and he, Mr Addo, agreed that what was happening was a food shortage.

“Food shortage, yes, but we don’t have a food crisis. I’m telling you that during the planting season every year, it has been like this. Just that this year because of Covid-19 and fertilizer production, everything about fertilizer (issues have become challenging),” he claimed.

Both the minister and his deputy tried semantic counterarguments. But unfortunately for the deputy minister, his boss does not think the MOFA has to accept that we are experiencing a food shortage.

Before the minister and his deputy would express confusion over what to call Ghana’s problems, The Ghana Report had spoken to agricultural tech and research firm Esoko in July about what they would call it.

Francis Danso-Adjei, a Content Manager with Esoko, referred to the problem as food insecurity, the fact of which means there is not enough in Ghana to feed Ghanaians.

“Now, demand for domestic and industrial use is far outstripping the supply that we have. The volumes available currently are not able to meet the demand, so, you see that prices going up,” Danso-Adjei put forward.

In May, the CEO of the Ghana Chamber of Agribusiness, Anthony Morrison, also warned that Ghana was facing “food insecurity”, explaining that the era of COVID-19 had exposed the weaknesses of not having a national seed bank in the country.

Ghana imports nearly 90 percent of seeds for vegetables and many other crops. This problem has not been addressed by successive governments for the longest time.

Gauging the food situation from the perspective of non-partisan stakeholders is necessary for an accurate representation. And so we contacted the Ghana Agricultural Workers Union (GAWU) for their take but at the time of going to press, they had not responded.

In spite of this, we have been witnesses to the desperate defensive performances by Dr Akoto against GAWU and the Peasant Farmers Association of Ghana (PFAG). Indeed, the minister specifically accused both associations a few weeks ago of “lacking data” to back up their claims of a food shortage in Ghana.

Both GAWU and PFAG, in the middle of this year, made pronouncements that Ghanaians should expect to pay more for food in the coming year, partially because the government’s fertiliser distribution programmes have proven ineffective and harvests were going to suffer.

What is most interesting is that Dr Akoto seemed to have agreed with both stakeholder associations at the Fertiliser for African Agriculture forum in Accra. He had regretted the lack of information with respect to the reach of Ghana’s fertiliser distribution programmes, saying that it was possible the full potential of the government’s intervention was not being realised.

For years, Ghana’s MOFA has relied on extension officers and local government agricultural directors to report on intervention programmes. These same sources on the ground have also been reported to stakeholders including GAWU, PFAG and others.

When stakeholders make pronouncements and forecasts, it is safe to assume that they possessed data that was similar to what the government has. Dr Akoto’s accusation of these stakeholders was therefore strange and unproductive yet, he trudged on.

Perhaps, the minister did not want to have a public discussion on what constituted a policy failure on the part of the government. After all, if there is no fertiliser for crop farming or rather, little to no indication of an effective fertiliser programme, all fingers would point to the MOFA.

According to the ECOWAS Agricultural Policy (2006 Abuja Declaration), member countries need to post 50kg of fertiliser for every hectare of farmland. Ghana is posting about 25kg, according to the Alliance for Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA).

Thus, we have a clear indication that we are not meeting sub-regional expectations, for instance, with our movement towards food security. But this particular angle also dovetails into the government’s flagship Planting for Food and Jobs (PFJ) programme.

The programme was launched by President Nana Akufo-Addo at Goaso in 2017 in the then Brong Ahafo Region.

PFJ has five (5) implementation modules. As stated on the MOFA’s website, the first module of the PFJ aims to promote food security and immediate availability of selected food crops on the market and also provide jobs.

This was a laudable ambition to improve smallholder contribution to agriculture. One could even tell from the programme’s budget promises of GH₵ 3.3 billion over four years that the government was bent on going all out for this one. The entire budget for the MOFA in 2016, for example, was a little over GH₵ 500 million.

For the successful implementation of the PFJ, the government theorised a number of pillars, two of which will be of ultimate concern to us in this analysis.

The first pillar, which was to guarantee a healthy seed programme, has had some little success. For instance, according to a European Commission report on the FPJ between 2017 and 2020, nearly all seeds used under the programme is sourced through the Fertiliser Subsidy Programme (FSP) that was implemented by former governments.

This means that most seeds used under the FPJ are sourced locally

But the issue still remains that for four years, the FPJ under Dr Akoto has still not established a national seed bank. Of course, the movement towards establishing such an outfit has taken decades but we are no closer to the dream now than we were before 2017.

What does a national seed bank mean? If the point of the FPJ seed pillar is to improve seed use, seeding rates and to expand the seed varieties available to farmers, then a national seed bank structures that expectation.

In that way, the National Seed Policy of 2013 would have been more meaningful.

The second pillar, which is to improve fertiliser distribution to farmers through credits and subsidies of up to 50%, has not been anywhere as successful. Indeed, after the first year of the FPJ, the ministry seemed to have abandoned this pillar arguably because farmers could not repay, post-harvest.

If we delve into why farmers cannot reimburse the ministry for these credits, we may open another can of worms which is the difficulty in the transportation of food from deprived areas to the rest of the country because of a lack of feeder roads.

The government has even blamed the ineffective distribution of fertilisers on the activities of certain miscreants who smuggle into neighbouring countries.

But if what the PFAG and GAWU have said is anything to go by, those illegal activities do not constitute even half of why fertiliser distribution has been negatively impacted.

Conclusion

It would seem from the above that the MOFA seems eager to win a narrative war in the face of more concrete problems that it is struggling with. And it must be said that Dr Akoto is at the forefront of this narrative war.

But despite the understandable propaganda to fend off attacks from partisan detractors, the difficult tasks remain and unfortunately, it does not seem as if we are anywhere out of the woods yet. Responding to the critics of the government does not translate into effective solutions and problem management.

As it stands, all things point to the fact that we are in dire food times. Ghanaians will most likely now pay more for food, further exasperating current hardships and no amount of narrative-wrangling will save us.