James Bond is a man with no time to die, but plenty of experience being reborn. Since the character’s big screen debut in 1962’s Dr No, no fewer than seven actors have inhabited the 007 tux, with an eighth soon to join them.

- Bond can absorb whatever the culture is doing at the time and still be a Bond movie – Andrew Ellard

- The rise of the far right feels like something the Bond films have to reach for, because it’s impossible to ignore – Andrew Ellard

- It’s exciting to imagine a Moneypenny spin-off where the hero in this traditionally male-skewing universe is now a heroine, and she’s black – Jaap Verheul

This month’s latest instalment in the super-spy series is the last one to star Daniel Craig as the martini-sipping man of mystery, and as the release has neared, so has yet another wave of speculation about the actor set to follow him. Richard Madden, Tom Hardy and Bridgerton star Regé-Jean Page are among the rumoured recruits for MI6 service, but arguably the more fascinating question than who will play Bond is: what type of Bond will they get to play?

“Each time a new actor becomes Bond, the series takes the opportunity to recalibrate itself to the ideology of the audience it’s trying to talk to,” says Dr Jaap Verheul, editor of The Cultural Life of James Bond – a new anthology of academic essays on the secret agent. You only need to look at the last 007 changing of the guard to see his point. The Craig era began in 2006 with Casino Royale, a film set in the shadows of 9/11. Not only did the film pack a villain who, Judi Dench’s character M implies, conspired with al-Qaeda to carry out the attacks, but there was also a new tone to go with its new 007. Director Martin Campbell filled every frame with a grit reflecting the era’s cultural climate, in stark contrast to the cartoonishness of the spy’s previous outing.

“The first Bond movie that actually came out post 9/11 was 2002’s Die Another Day,” says Andrew Ellard, a screenwriter and script editor who’s been a Bond obsessive since childhood. “In that moment, the world was angry and paranoid and looking to understand the complexity of what had happened.” What the world got instead was a Pierce Brosnan-starring Bond movie full of invisible cars and campy ice lairs. “It just struck totally the wrong tone,” he says. A critical panning followed, leading to Brosnan’s dismissal and the search for a new start for the MI6 operative. Casino Royale, starring a haunted-looking blond with a cold detachment in his eye, was the result of that reset, re-tuning the character for a time of terrorism and geopolitical paranoia.

Bond can absorb whatever the culture is doing at the time and still be a Bond movie – Andrew Ellard

The series’ look and feel was updated, too. Critics, Verheul points out, drew comparisons between Casino Royale and “the Christopher Nolan Batman movies and The Bourne Identity, which had been huge hits and had a much more realistic style.” Bond, however, is such a huge cultural entity that it “can absorb whatever the culture is doing at the time and still be a Bond movie,” as Ellard puts it. “Brosnan’s first movie, Goldeneye, was full of henchmen getting machine-gunned, which was very much a response to Die Hard and the action boom of the late ’80s, [while] over the years, we’ve had elements of Blaxploitation and [1970s martial arts genre] Chopsocky in Bond. Things even got a bit Thunderbirds-y in the middle of the Roger Moore films.”

Certainly, Casino Royale’s changes were not a one-off. Every time a new Bond collects their Walther PPK and licence to kill, the series tends to update itself aesthetically, politically and otherwise. So what does this mean for the future of series? How does the 007 saga update itself to reflect a time of misinformation, Brexit and a looming climate crisis? And in a post-Marvel world where franchises are being fragmented into streaming service spin-offs, are we staring down the revolver barrel of a Bond cinematic universe?

Keeping up with modern values

“The world has moved on, Commander Bond. So stay in your lane. Or I will put a bullet in your knee.” So says actress Lashana Lynch in the trailer to No Time To Die, in her role as Nomi – a Black female operative who’s replaced Bond as the agent known as 007. It’s a continuation of a gradual course correction within the Craig era towards more empowered female characters, after decades of behaviour by Bond that’s now recognised as sexist. “He’s incredibly good-looking and incredibly well-dressed. He always survives and he sleeps with a lot of women. If you’re a straight white dude, for a long time, it’s been very easy to go to Bond for wish fulfilment,” says Ellard. From the hiring of Fleabag star Phoebe Waller-Bridge to help finesse the No Time To Die script to the recent reimagining of secretary character Moneypenny (now played by Naomie Harris) as a field-operative equal to Bond (instead of the office-bound object of his leering), Bond has been on a pathway to better female representation that’s set to continue into whatever comes next.

“The sexism has certainly improved but there’s still more distance to run in that regard. Skyfall had a scene where Bond sneaks into a women’s shower, for example, which raises all sorts of questions about consent,” says Ellard. “How do you solve a problem like that? You put a woman on the writing team, or have a woman direct it.” With filmmakers like Wonder Woman’s Patty Jenkins, Black Widow’s Cate Shortland and The Old Guard’s Gina Prince-Bythewood waiting in the wings, all with acclaimed action movies behind them, there’s certainly no shortage of women candidates to step into the director’s seat on Bond 26.

Whoever’s in charge may also decide to continue the series’ recent introspective approach to the character’s past toxic behaviour. “There’s xenophobia and imperialism built into Bond, not to mention all sorts of homophobia,” says Ellard. “How you roll with that and make it work in modern times is a difficult question for whoever’s making these movies, because this is a character built on a certain way of representing privilege and superiority that doesn’t sit easily in 2021.” In the Craig era, screenwriters Neal Purvis and Robert Wade found an inspired creative solution to this problem: feed that tension directly into the script, turning the discourse around Bond and his behaviour into dramatic tinderwood.

The rise of the far right feels like something the Bond films have to reach for, because it’s impossible to ignore – Andrew Ellard

After Goldeneye heralded the introduction of a female M, who accused Bond directly of being a “sexist, misogynist dinosaur” and “relic of the Cold War”, the Daniel Craig films got “ahead of the march on the question of how Bond can exist in 2021,” says Ellard. “[It did this] by actively saying: it’s not great that he’s killing people. It’s not great that he can cope with the blood on his hands, and for that just to be part of who he is.” He points to the way that Casino Royale reframed the character’s celebrated drinking as a coping mechanism for the guilt simmering within him as just one of the smart balancing acts. “There’s some gorgeous stuff in that film where he’s looking haggard in the mirror and you’re forced to say, ‘I’m not sure I aspire to be that guy’. That was such an important reinvention.” Bond 26 and beyond could decide to lean even further into the tension between the values Bond has represented in our culture, and how out of place those values seem now.

A new era of villainy?

You can tell a lot about an era by the Bond movies released in it, suggests Verheul. Case in point? “The number of the women that Bond sleeps with, either on screen or implied. In the 1980s, for example, concern about the Aids pandemic had an influence on the character’s promiscuity. Timothy Dalton’s Bond was a much more prudent version of Bond as a result.” Along the same lines, in Casino Royale and the Craig films that followed it, we saw what Ellard describes as “a greater willingness to question whether the people running your country are entirely virtuous. In Quantum of Solace, it’s very clear that the CIA are not good people. Bond ends up discovering that the CIA and British government are in cahoots, backing the machinations of [the criminal organisation] Quantum.” It’s no accident that this emerged as a theme in a time of mass scepticism over the US and Britain’s invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan.

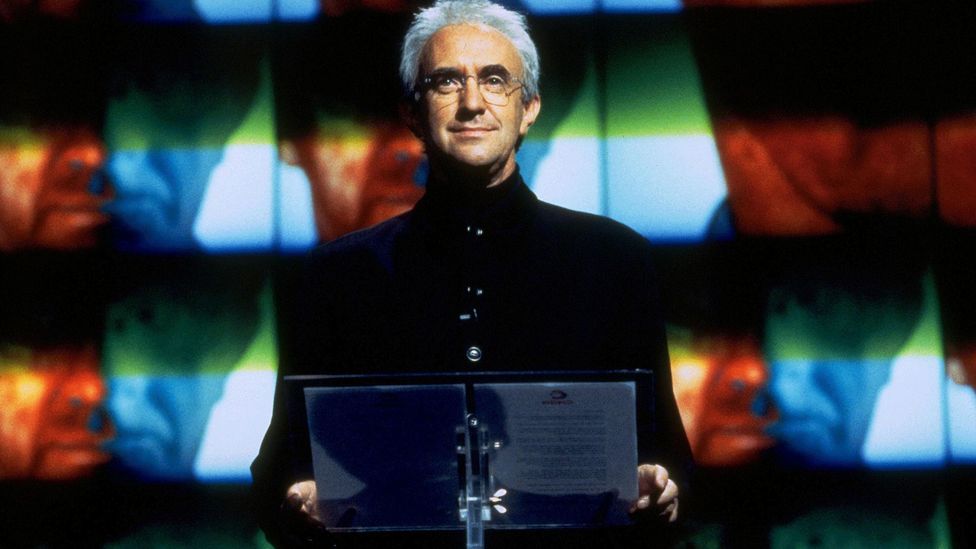

The geopolitical landscape is even more complicated today than the one Craig stepped into in 2006. Where Casino Royale introduced a shadowy threat informed by the perpetrators of the 11 September attacks, the next incumbent of the 007 director’s chair will have misinformation, climate change and cyber warfare as potential jumping off points. The series has never shied away from pulling inspiration from real-life for its antagonists – 1997’s Tomorrow Never Dies featured a plot about a megalomaniacal media mogul that was a thinly veiled amalgamation of Fox owner Rupert Murdoch and the press baron Robert Maxwell. In most instances though, there’s still a certain extravagance to be added: Murdoch, to the best of this writer’s knowledge, has never sought to spark a war between the UK and China in order to boost any of his news networks. 2021, however, is a time of super-rich, super-powerful figures who some might argue resemble real-life, ready-made Bond villains (naming no names). So how do you write a Bond villain for 2021 and beyond?

Bond villains, like Tomorrow Never Dies’ Rupert Murdoch-inspired media mogul Elliot Carver, have always reflected real-world concerns (Credit: Alamy)

“The emergence of the far right would be an enormous concern to any version of Bond,” suggests Ellard. “Although it’s broadly a conservative, slightly right-wing franchise about British heroes who don’t trust foreigners, there’s very clearly a line in the sand – they don’t like Nazis. The rise of the [far] right… in Britain and America and France feels like something they have to reach for, because it’s impossible to ignore.” Alternatively, it could be that climate change forms inspiration for a villain. “There are people in existence right now who are rich enough to stop global warming from happening. Their choice not to act, that’s a form of villainy [that] it’d be interesting to explore.”

It’s exciting to imagine a Moneypenny spin-off where the hero in this traditionally male-skewing universe is now a heroine, and she’s black – Jaap Verheul

One thing is for sure – don’t expect the trope of these villains having facial deformities to continue for much longer. “You’ve got Le Chiffre [from Casino Royale, played by Mads Mikkelsen] with his weeping tear duct. You’ve got Silva [from Skyfall, played by Javier Bardem] with his face dissolved. And now we’ve got Safin [in No Time To Die, played by Remi Malek] with a mask and facial disfigurement. Those things feel like a legacy of a past time,” says Ellard, noting that in Spectre, the last Bond movie, “they even managed to scar Blofeld [played by Christoph Waltz] along the way.” In the Ian Fleming books that started it all, it was Bond who had the facial scar. In the author’s Casino Royale novel, he describes Bond as possessing “a dark, clean-cut face, with a three-inch scar showing whitely down the skin of the right cheek.” After criticism from campaigners, alleging that depicting villains with deformities reinforces negative stereotypes and make the lives of real-life sufferers harder, it’d be a welcome reversal to introduce a scar to the right cheek of the titular hero in the next Bond outing just as Fleming originally envisioned.

The Bond cinematic universe?

Another question on the horizon for Bond fans is what Amazon’s new part-ownership of the franchise will mean for 007. The corporation has a streaming service to drive subscribers to, and the industry’s made a major turn towards “cinematic universes” in which stories are spread across a variety of films, TV shows, video games and more. Marvel initiated the trend with the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Star Wars then followed suit, with a wide slate of interconnecting titles set to start debuting later this year following the success of Disney+ show The Mandalorian. DC have tried it, and the Fast and Furious franchise is headed that way too. Will Jeff Bezos seek to maximise the earning potential of 007 by creating a wealth of new Bond-related content?

There is a precedent for it, says Verheul. “In the medium of comics, there’s a Latin American Bond who has been very successful. Bond novels are written in that format. I’d certainly be curious to see it. It’s exciting to imagine a Moneypenny spin-off where the hero in this traditionally male-skewing universe is now a heroine, and she’s black. I think there’s a market for that,” he adds.

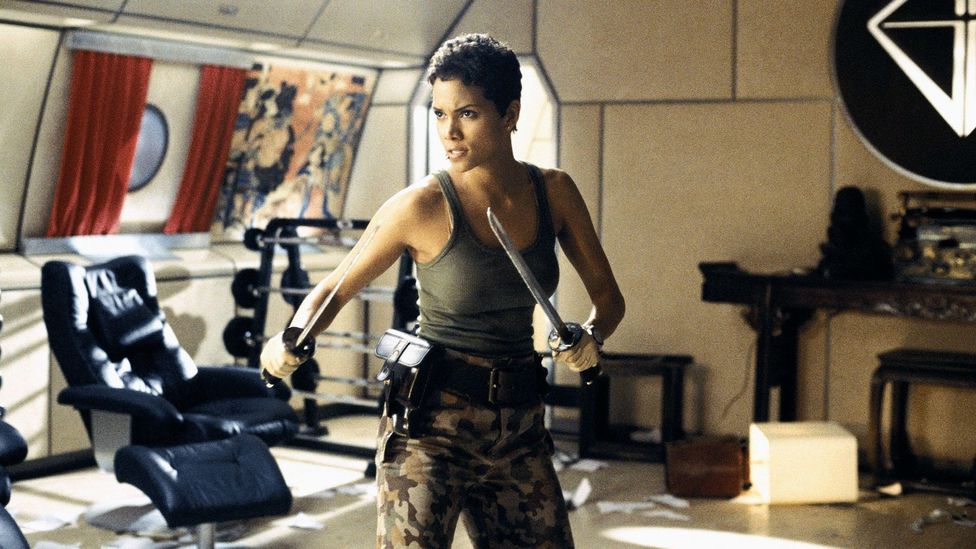

Ellard points out a spin-off almost happened, years ago. “They were going to do it with Halle Berry’s character from Die Another Day. The script was written, but that never happened.” Ultimately, he suspects the scarcity of Bond movies is key to its aura of sophistication. “You can’t appear quite so high end if you’re making loads of things all the time. I love the MCU, but you can see the functioning conveyor belt. Bond has set itself apart as a rare jewel. You only get one every few years.” If there were four Bond-related things coming out every year, akin to the Marvel Cinematic Universe, it’s unlikely the Bond brand would get stronger.

A Bond spin-off starring Halle Berry’s character never materialised – but there could now be spin-offs to come (Credit: Alamy)

Whatever happens, and whoever’s tossed the keys to the character’s Aston Martin after Daniel Craig departs, there are some things about 007 that will never change, however. “There’s a lot of panic about the cultural politics of Bond,” says Verheul, alluding to a lot of media hand-wringing about Bond going “woke” in the new film (“the wokest Bond ever” British newspaper the Daily Mail gasped in 2019 after reports that Bond would drive an electric Aston Martin in No Time To Die). But Bond ultimately will always come down to a few central facets, he believes. “The appeal is a certain formula: the gadgets, the glamour of international travel, some kind of romance and big action set pieces that aren’t shot in front of a green screen. Add to that the association of Bond with Britishness – and I don’t think it’s important how that Britishness is defined, good or bad, so long as it’s engaging with it – and that, ultimately, is what makes a Bond film.” James Bond is about to be reborn again, and after the revitalising Daniel Craig era, the possibilities feel endless. Step forward, whichever actor is next in line – we’ve been expecting you.

No Time To Die is released in the UK on 30 September and in the US on 8 October