UK apology sought for British war crimes in Palestine

The people of al-Bassa got their lesson in imperial brutality when the British soldiers came after dawn.

Machine guns mounted on Rolls Royce armoured cars opened fire on the Palestinian village before the Royal Ulster Rifles arrived with flaming torches and burned homes to the ground.

Villagers were rounded up while troops later herded men onto a bus and forced them to drive over a landmine which blew up, killing everyone on board.

A British policeman photographed the scene as women tended to the remains of their dead, before maimed body parts were buried in a pit.

It was the autumn of 1938 and UK forces were facing a rebellion in Palestine, under British control after the defeat two decades earlier of the Ottoman Empire.

Britain’s raid on al-Bassa was part of a declared policy by the local commander of “punitive” action against entire Palestinian villages – this one after a roadside bomb had killed four British soldiers – regardless of any evidence over who was responsible.

The atrocity was revealed in accounts by soldiers and villagers decades after the UK left. It now forms part of a file being brought to the British government seeking accountability for Palestinians subjected to alleged war crimes by UK forces.

The petition, involving a 300-page dossier of evidence, asks for a formal acknowledgement and apology for abuses during the period of British rule in Palestine from 1917 until 1948, after which Britain rapidly withdrew and the State of Israel was declared.

A BBC review of the historical evidence involved includes details of arbitrary killings, torture, the use of human shields and the introduction of home demolitions as collective punishment. Much of it was conducted within formal policy guidelines for UK forces at the time or with the consent of senior officers.

“I wanted people to know that my parents, as young as teenagers, they suffered. And those who died, we have to speak for them now,” said Eid Haddad, the son of two survivors of al-Bassa, speaking to BBC Newsnight.

In a statement the UK Ministry of Defence said it was aware of historical allegations against armed forces personnel during the period and any evidence provided would be “reviewed thoroughly”.

The request for an apology is likely to reopen the debate over delivering modern-day accountability for colonial-era crimes, while also being viewed in the context of the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

The two communities assess Britain’s historical legacy from different standpoints, while both at varying times resisted hostility, abuses or broken promises during UK rule.

It is being brought by Munib al-Masri, 88, a well-known Palestinian business owner and former politician, who was shot and wounded by British troops as a boy in 1944.

“[Britain’s role] affected me a lot because I saw how people were harassed… we had no protection whatsoever and nobody to defend us,” Mr al-Masri told the BBC at his home in Nablus in the occupied West Bank.

Two senior international lawyers are involved in the project, asked by Mr al-Masri to carry out an independent review of the evidence. They are Luis Moreno Ocampo, former chief prosecutor at the International Criminal Court, and the British barrister Ben Emmerson KC, former UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and counter-terrorism.

Mr Emmerson says the legal team has unearthed evidence of “shocking crimes committed by certain elements of the British Mandatory forces systematically on the Palestinian population”.

“They are some of them of such enormous gravity that they would have been regarded even then as breaches of customary international law,” he told the BBC.

Barbed wire cages

Mr al-Masri is due to present the file to the UK government in London later this year.

His petition refers to another atrocity in the summer of 1939, when soldiers from the Black Watch regiment carried out a weapons search of the village of Halhul, which lies in the West Bank.

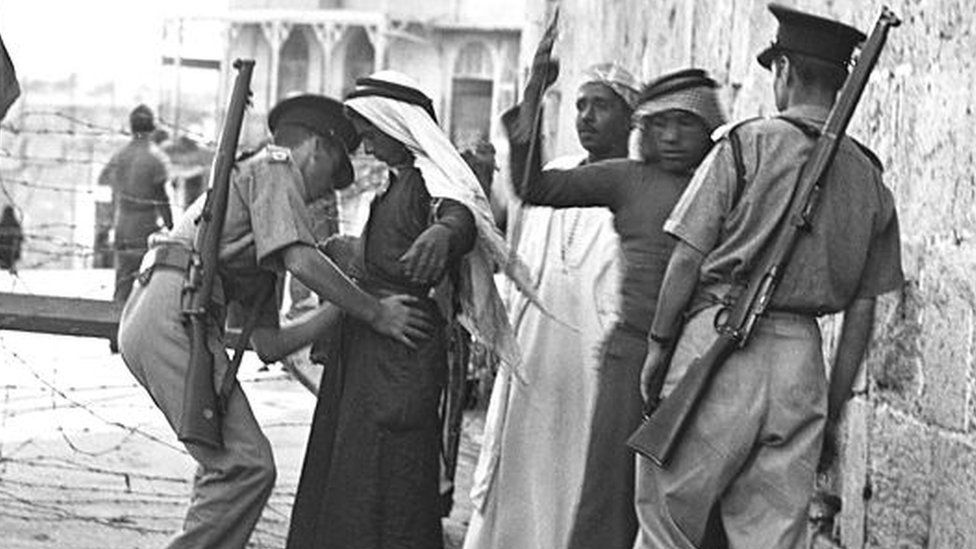

Multiple accounts from both residents and British soldiers detailed how homes were raided and villagers rounded up at gunpoint, before up to 150 men were herded into a space behind a mosque and many forced into barbed wire cages.

“These were not revolutionaries, they were farmers. The revolutionaries were hiding in mountains,” says Mohammed Abu Rayan, 88, who was a boy when the British soldiers stormed his home and occupied the rooftop.

He knew many of the survivors of the cages of Halhul. During a fortnight of captivity in the sweltering heat, 13 people died of dehydration, while at least one was shot trying to escape.

“They started digging the soil to try to eat the roots. They put wet dirt on their skin just to try to cool down,” Mr Abu Rayan told the BBC at his home in Halhul.

A British official at the time put the death toll slightly lower.

“After 48 hours treatment most of the men were very ill and 11 old and enfeebled ones died. I was instructed that no civil inquest should be held,” wrote then-district commissioner Edward Keith-Roach in a private letter.

An extraordinary account given decades later by Lt Col Lord Douglas Gordon, a former Subaltern of the Black Watch regiment, revealed the existence of a “good cage” with tents for shelter and unlimited water, next to the “bad cage [where] they had no shelter, they were rationed to, I think, one pint of water a day.”

Growing tensions

Britain’s control of Palestine began during World War One when its imperial forces drove out Ottoman Turkish troops. In 1917, Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour pledged to the Zionist movement to establish a Jewish national home in what became known as the Balfour Declaration.

The UK was given a mandate to govern, allowing levels of Jewish immigration and land acquisition to rise, fuelling growing tensions with Palestinian Arabs that frequently broke out into violence.

Britain’s three decades-long presence saw a series of chaotic policy reversals as troops struggled to contain growing violence – both between Palestinians and Jews and, at different times, by armed groups from both sides against UK forces.

A Palestinian insurgency – known as the Arab Rebellion – broke out from 1936, and London flooded the country with troops.

Britain’s atrocities carried out in Palestine were “violent and sensational” but “exceptional”, according to the military historian Prof Matthew Hughes, who says its tactics did not routinely reach the levels of brutality meted out in some other colonies.

Instead, he says, Britain introduced a system of “daily pacification” that was “much more fundamental, cumulative and attritional in wearing down the Palestinians”, citing measures including restrictions on movement, curfews, seizure of property or crops as punitive measures, arbitrary detention and using forced labour to build roads and military bases.

“The whole country became something of a prison,” says Prof Hughes, author of Britain’s Pacification of Palestine.

He also says the UK’s military guidelines allowed troops to carry out “collective punishments” – often involving home demolitions – as well as “retribution” and the shooting of rioters, while it was also commonplace to shoot suspects who were running away.

‘Belted and bashed’

The recollections of many British soldiers and police officers in Palestine are found in the archives of the Imperial War Museum in London. Some of the oral history tapes detail accounts of “punitive” raids, the use of human shields and torture.

Fred Howbrook, an officer in the Manchester Regiment, said they would go to villages and “smash up a few houses, things like that” while residents could only watch.

Another soldier with the Manchester Regiment, Arthur Lane, described how they would “go down to Acre jail and borrow say five rebels, three rebels, and you’d sit them on the bonnet, so the guy up in the hill could see an Arab on the truck so he wouldn’t blow it… If [the rebel] was unlucky the truck coming up behind would hit him. But nobody bothered to pick the bits up. They were left.”

He also spoke of a practice called “running the gauntlet” in which Palestinian suspects were made to run between two lines of British soldiers and were “belted and bashed” with rifle butts and pick axes. “Any that died, they went into the other meat wagon and they were dumped in one of the villages outside,” he said.

The Mandate period saw the UK ultimately use “rather nasty methods of control” over both Jews and Arabs, says the Israeli historian Tom Segev, author of One Palestine, Complete.

“The British as early as 1937 realised that it can’t work, that they should really get out of here… that the conflict between Jews and Arabs doesn’t really have a solution,” he told the BBC.

While many Israelis remain grateful for the Balfour Declaration, Mr Segev says by the 1940s the tension between the Zionists and the British increased “very badly”. “Some Jews felt that the British [were] betraying them,” he says.

The period saw Britain turn back ships of survivors of the Nazi Holocaust who were attempting to get to Palestine.

“They were very tough rulers and all they wanted was: ‘Be quiet, don’t bother us with your problems, we don’t really care who is right and who is wrong’. And so they implemented very bad methods of operation,” says Mr Segev.

Meanwhile, Mr al-Masri seeks to argue that the ensuing conflict left the Palestinians entirely vulnerable, as the newly created State of Israel adopted some of the emergency powers left by the British.

“Britain should see the ways and means to compensate… [to] be brave and say: ‘Sorry I did this’,” he says.