A farmer who makes an effort to check on his crops four times a year might feel puzzled about why his harvest isn’t as plentiful as he had hoped.

In the same way, a captain who gives his compass just a quick glance once every season might discover his ship is veering off course.

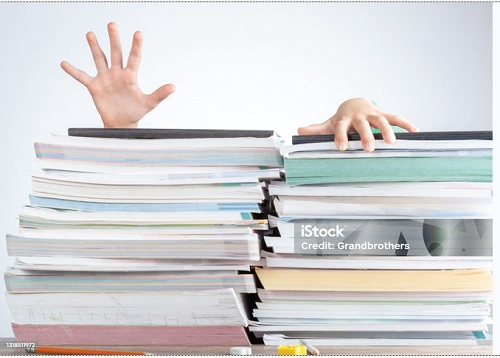

This concept applies to businesses in developing economies, too; putting off action can create hurdles later on.

The traditional boardroom model, meeting just four times a year, feels a bit outdated in today’s ever-changing world.

This approach thrives in environments where inflation is steady, policies are consistent, infrastructure holds strong, and financial markets behave reliably. In these situations, businesses can look ahead with assurance, understanding that economic surprises are rare rather than the usual experience.

In developing economies, stability is a fragile illusion.

Currencies can lose half their value overnight, tax laws can change without warning, supply chains can collapse due to infrastructure failures, and foreign investments can disappear at the stroke of a policy change In this environment, a business that meets only four times a year reacts instead of leads, watches problems escalate instead of preventing them.

The inconvenient truth is simple: Boards in developing nations must convene with greater frequency to not only survive but also to prosper.

The regulations governing their interactions differ significantly.

The stakes are considerably elevated, and the repercussions of inaction can be catastrophic.

A board that fails to anticipate economic, regulatory, and infrastructural disruptions is a board that is sleepwalking toward irrelevance.

The question is no longer whether frequent board meetings are necessary but whether businesses can afford not to have them.

The reality is stark; businesses in developing nations need governance structures that reflect the harsh terrain they operate in.

A reactive board is a failing board.

A proactive board is a surviving board.

And only those who adapt quickly will shape the future, while the rest become history.

The economy moves like a storm, not a clock

In a land where the wind changes direction without warning, only a fool sails with yesterday’s map. In developed economies, policies, currencies, and markets move with measured precision.

A business can plan five years ahead, confident that inflation will remain within manageable limits, taxation policies will stay stable, and investment climates will continue to be welcoming; not so in developing nations. Here, a company’s financial model can collapse between board meetings.

Example — Nigeria’s Naira Freefall. Nigeria’s Naira has suffered multiple devaluations in short periods, forcing businesses to rewrite financial projections multiple times a year.

If a company waits until its quarterly board meeting to adjust its strategy, it may be too late.

In October 2023, Nigeria floated its currency, causing an immediate spike in inflation. Import-heavy businesses saw their costs double overnight.

A board that met only four times a year would have been paralysed, leaving the company haemorrhaging cash while competitors pivoted. Boards in such economies must meet frequently to:

First, adjust financial strategies based on real-time economic shifts; secondly, reevaluate investment decisions as inflation and interest rates change and finally decide on immediate measures to hedge against economic risks.

A board that meets too late is a board that meets for autopsies instead of solutions.

Policy Instability — A game where the rules change overnight

A merchant who sets his prices in the morning may find his goods worthless by evening.

In developed economies, policies remain consistent over long periods.

Businesses can plan years ahead without worrying about sudden policy reversals.

In developing economies, governments frequently change policies, taxation rules, and business regulations overnight.

Example — Kenya’s rapid tax policy shifts Kenya’s finance. Act 2023 introduced tax measures that significantly affected businesses.

VAT on fuel increased, and new digital transaction levies were introduced. Companies that failed to adapt quickly bled cash before convening their next quarterly board meeting.

Example — Ghana’s unstable tax policies. Ghana’s E-Levy, introduced to tax electronic transactions, immediately impacted businesses reliant on mobile money payments. Companies had to swiftly adjust financial models, while others waited too long and suffered massive revenue declines.

A business in a developing economy must meet frequently to adapt to sudden tax and regulatory changes; engage with policymakers before damaging laws take full effect; and restructure pricing models before losses become irreversible.

When the market moves like shifting sand, only a fool builds a house without checking the foundation frequently.

The danger of overreach: The board must not cross the line into executive duties

When the shepherd starts ploughing the field, the flock is left unguarded. When the board starts managing operations, governance collapses.

While increasing board meetings is necessary in developing economies, there must never be an overlap between supervisory duties and executive functions.

The board’s role is to provide oversight, strategic direction, and risk management, not to run day-to-day operations.

In the bid to circumvent the four-times-a-year model, there is an increasing tendency to call frequent emergency meetings.

While emergency meetings have their place, they must not become a substitute for structured governance.

A board that meets too often without clear agenda-setting risks micromanaging executives instead of guiding them; losing focus on strategic long-term goals due to reactionary decision-making; and creating an unstable governance environment where managers operate under constant scrutiny instead of empowered leadership.

Finding the right balance is essential! It’s important to increase board meetings when necessary while maintaining clear, healthy boundaries.

Remember, boards are here to support and guide, not to take over; their role is to provide direction, not to get involved in every detail.

When we achieve this harmony, it leads to better outcomes for everyone involved.

Conclusion: The urgent need for a new governance model

A farmer who inspects his land only four times a year should not expect a strong harvest. A board that meets four times a year in a volatile economy should not expect to survive the storm.

The world will not wait for developing economies to catch up. Markets are ruthless, competition is relentless, and survival favours the fast and the prepared.

Businesses in fragile economies cannot afford the luxury of slow decision-making.

However, frequent board meetings must not substitute for strong governance.

Oversight should be strategic, not operational; supervision must be rigorous but not overbearing; and decisions must be timely, not reactionary.

Boards must evolve from ceremonial gatherings into war rooms of strategic agility.

First, they must meet more frequently to anticipate disruptions rather than react to them; they must shift from passive oversight to proactive leadership; and they must act swiftly to ensure their companies remain competitive, profitable, and resilient.

The most powerful economic empires were not built through caution or red tape.

Rather, they were created through audacious actions, strategic adjustments, and unapologetic dedication to overcoming obstacles.

Achieving economic strength requires long-term vision, proactive decisions, and a spirit of adaptability.

For businesses in emerging economies, simply waiting for stability is not viable; they must take charge with decisive and motivating leadership.

In the rapidly evolving landscape of developing economies, procrastinating until the next board meeting may lead to missed critical opportunities.

Therefore, it’s essential to act now!