If you walk into a doughnut shop in California, the chances are it’s owned by a Cambodian family. That’s because of a refugee who built up an empire, and became known as the Donut King, only to lose it all.

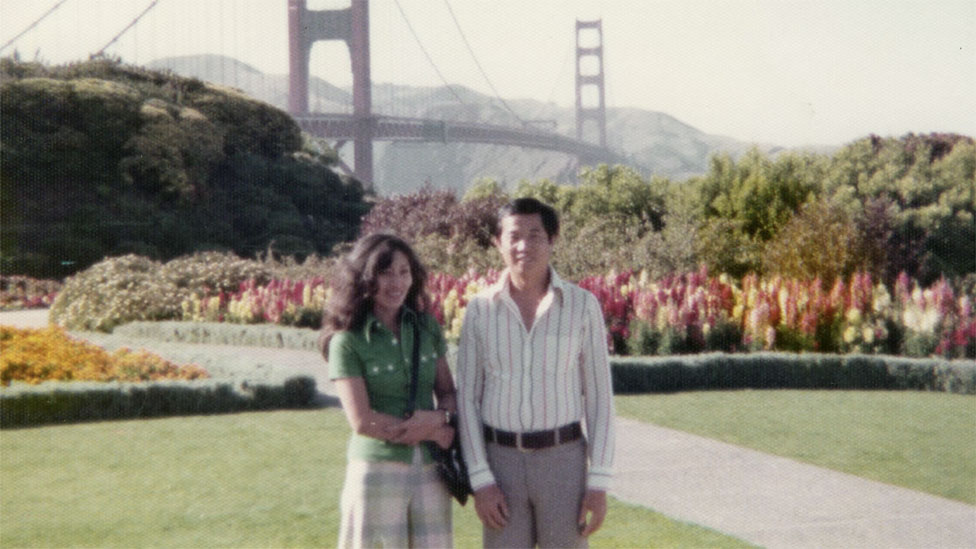

Ted Ngoy was a high school student in Phnom Penh when he first set eyes on Suganthini Khoeun, the daughter of a high-ranking government official.

“She was so beautiful,” he remembers. “You can’t find any prettier woman besides her.”

All the boys at his school were in love with her, and as a poor half-Chinese boy from a village near the Thai border he had no chance. “She was powerful, like your royal princess,” says Ted. And she was heavily chaperoned.

But then Ted discovered that the tiny room where he lodged, on the fourth floor of a walk-up apartment block, overlooked Suganthini’s villa. And he saw an opportunity. Every evening, he sat by his open window and played the flute.

On hearing the music float across the quiet city, Suganthini’s mother remarked that whoever was playing must be in love.

One night, he saw Suganthini on her balcony, and decided it was time to make his move. He wrote a note, telling her that he lived in the building opposite and was the flute player. He wrapped the note around a stone, and threw it down.

His gesture went unreciprocated for days. But then one of Suganthini’s servants appeared at his door with a reply.

“The note said, ‘I appreciate you blowing the flute. It’s so amazing, so touching.’ And then we started communicating, bringing back and forth the messages,” Ted says.

“What happens if I decide to jump into your room?” Ted wrote one day.

Suganthini replied, “Well be careful, if you don’t jump into my room, you’ll jump into my mum’s room.”

She thought Ted was joking, but he was serious. Despite the villa’s armed security guards and guard dogs, one rainy night Ted climbed up a coconut tree and over the barbed wire and made his way in through a bathroom window.

He took a chance and opened a bedroom door – and there was Suganthini, fast asleep.

He woke her up and she was about to scream for help, when she realised it was her classmate.

“What are you doing here?” she asked.

“Well, it is because I’ve fallen in love with you,” Ted replied.

“But what shall we do in the morning? I have to go to school.”

“Don’t worry, I will hide under your bed,” said Ted. And that’s what he did.

Suganthini smuggled him food at night, and after many days she said she loved him too. They made a blood pact, promising to be forever faithful. He says he hid in her room for 45 days until he was discovered.

Suganthini’s family insisted Ted break it off by telling her he didn’t love her. He did as he was told, but then pulled out a knife and stabbed himself, declaring he would rather die than live without her. While he was recovering in hospital, Suganthini also made an attempt on her life. Faced with such determination, her family allowed the young lovers to be together.

“It’s a crazy story, but it’s true,” says Ted, now 78. “I had true love for her.”

But he admits he was also aware that conquering Suganthini’s heart held out the promise of a better life.

They married and started a family, and life was good until civil war broke out in 1970, between the government and the communist Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot.

Ted, who spoke four languages, was offered a post as liaison officer in Thailand by Suganthini’s brother-in-law, Gen Sak Sutsakhan. Instantly acquiring the rank of Major, Ted and his young family moved to Bangkok, and every month he travelled back to Cambodia to collect the wages for his soldiers.

But the situation at home was increasingly dangerous and on his last trip, in April 1975, the capital fell. Ted managed to escape on the last flight out of Phnom Penh but Suganthini’s parents were left behind. She later discovered that they were among the first to be executed by the Khmer Rouge.

The following month, US President Gerald Ford insisted the US should welcome 130,000 refugees from Vietnam and Cambodia, telling any critics: “We’re a country built by immigrants from all areas of the world, and we’ve always been a very humanitarian nation.”

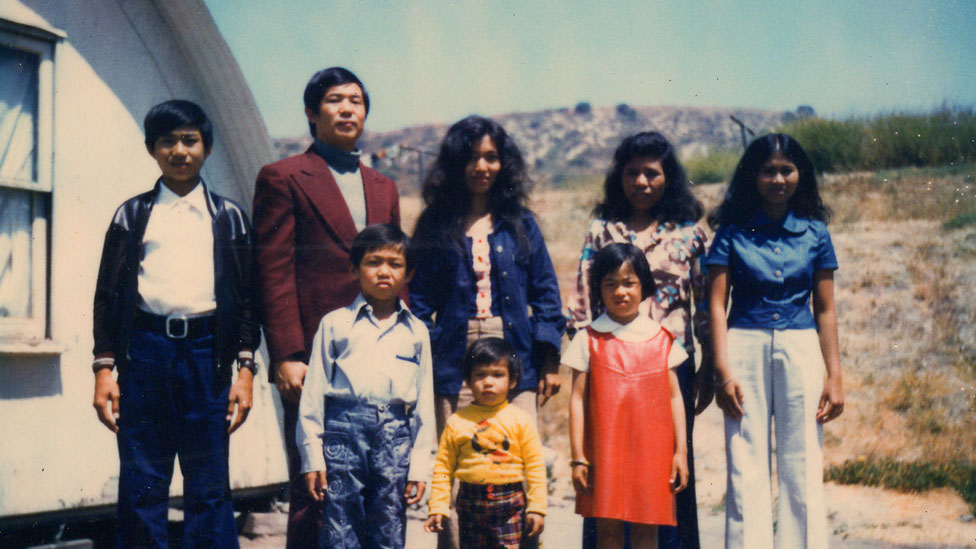

Ted and Suganthini sold everything they had and arrived in California on one of the first refugee flights, with their three children, an adopted nephew and two nieces. The family were housed in a hastily erected refugee camp on a marine training base, Camp Pendleton. In order to be allowed to leave the camp and find work, they needed an American sponsor, who would find them a job and somewhere to live.

For weeks, they watched other families leave, until finally they, too, were sponsored by a pastor from a church in Tustin, Orange County, about 35 miles south of Los Angeles. Ted worked as the church janitor but he soon realised earning $500 a month wouldn’t be enough to support his family. With the pastor’s permission he went out and got two more jobs, as a sales person from 6pm to 10pm and petrol attendant from 10pm to 6am.

Next to the petrol station there was a doughnut shop called DK Donuts. It smelled delicious and when he first tasted one it reminded him of something from home – a fried pastry, also circular, called nom kong. “It made me homesick,” says Ted.

All night long Ted would watch people buying coffee and doughnuts, and he realised it was a good business. One night he asked the woman at the counter if saving $3,000 would be enough to buy a doughnut shop. She said he would be throwing his money away. Instead, she told him about a training programme run by the doughnut chain, Winchell’s. Ted became their first South East Asian trainee.

“I learned to bake, to take care of payroll, cleaning, sales – everything,” he says. One of the tricks he learned was to bake doughnuts in small batches throughout the day to keep them fresh – and because the smell of baking was the best form of advertising.

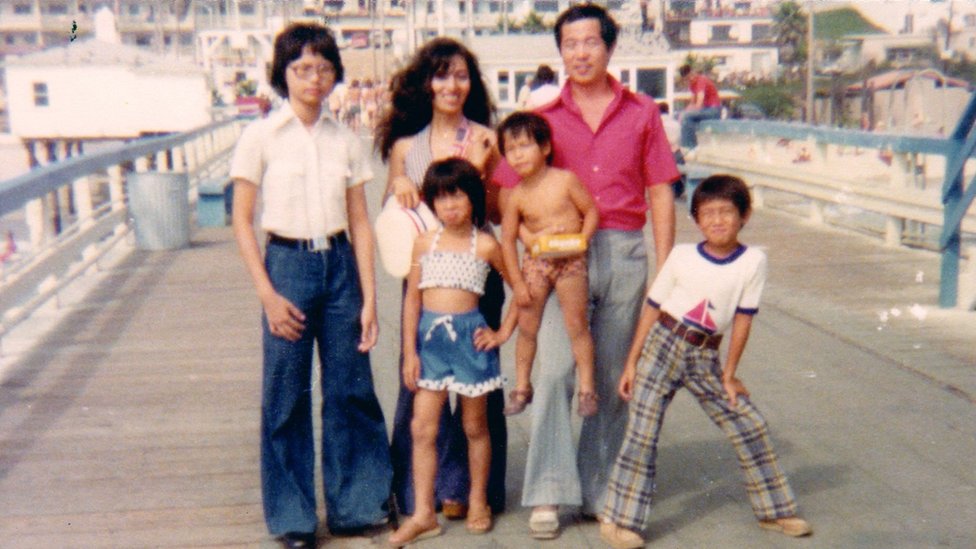

When he completed his three-month training, Winchell’s gave him a shop to run on Balboa Pier, a tourist spot on the Newport peninsula not far from Tustin. Suganthini became the smiling face behind the counter, even though she hardly spoke any English. Ted did a lot of the baking at night, with his youngest son, Chris, collecting a light dusting of flour as he slept beside him in the kitchen.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTTED NGOY

IMAGE COPYRIGHTTED NGOYThey saved money where they could, even washing and reusing coffee stirrers – until they were reprimanded by Winchell’s. When there was an overrun of pink doughnut boxes Ted bought them cut-price, and the pink boxes became his trademark.

The family worked 12 to 17 hours a day, with all hands on deck. At the weekend the oldest children, Chet and Savy, then nine and eight, helped out by pouring coffee, packing doughnuts and folding boxes. During the week they went to school, where sometimes they were so hungry they stole snacks from other kids’ lunchboxes.

In a year Ted had saved enough to put down a deposit on a second doughnut shop, a “mom-and-pop” shop called Christy’s. Once again Suganthini was the friendly face welcoming customers, and when she became a US citizen she took the name Christy as her own.

After a year of running two shops they had saved $40,000 and Ted decided to expand. He bought a bigger doughnut shop, and offered to lease the original Christy’s to a family of Cambodian refugees, who had been working in fast food outlets on low wages. He trained them and handed over the keys.

Ted began to look for more doughnut shops to buy and lease to fellow refugees. “Using money to provide for others is a feeling as powerful as any drug,” he later wrote.

Working all hours, Ted and Christy knew very little about what was happening back home in Cambodia, but what they heard was bad. They cried and prayed for the family they had left behind.

Under the Khmer Rouge leadership of Pol Pot people were forced to work on communal farms, and those with money or education were tortured and killed. Over four years nearly two million Cambodians were either executed, or died of starvation, disease and overwork.

In 1978 Vietnamese troops invaded and in 1979 Pol Pot was overthrown, leading to another wave of Cambodian refugees. Ted’s parents and sisters fled across the border to Thailand, and Ted got a call from the US embassy there asking if he would sponsor them to live in the US. Naturally he agreed, and set his sisters up with doughnut shops.

More and more relatives came forward for sponsorship. “Some of them were cousins, uncles, nieces,” says Ted. “But many of them were not related, they just lived in the same village or heard of my name. I think there’s nothing wrong for them to lie to the embassy because everybody needs a chance to survive. So, I just did it. As many as I could.”

Over the years, Ted and Christy sponsored more than 100 families, often hosting them before setting them up with homes, loans, and doughnut shops. Ted encouraged others to do the same. “It went like fire on the hill, so fast,” says Ted.

The Cambodians worked hard and because the whole family pitched in, they did not have to pay out any wages. It provided a path for refugees to settle and was a profitable business model. Eventually Cambodians owned so many doughnut shops in California that they dominated the market, pushing Winchell’s into second place.

It’s something Ted feels a bit bad about. “They’re a good company and I owe them gratitude,” Ted says. “Cambodian people owe them a lot.”

IMAGE COPYRIGHTTED NGOY

IMAGE COPYRIGHTTED NGOYBy 1985, 10 years after arriving in the US as refugees, Ted and Christy were millionaires, owning around 60 doughnut shops. Ted became known as the Donut King – or Uncle Ted, because of the many Cambodian immigrants he’d sponsored. The couple had flash cars, bought a million-dollar mansion with a pool and an elevator, and went on holidays abroad.

“I achieved my American dream,” Ted says.

“We were happy – until the gambling came to wreck my life. The gambling is sad, the saddest part of my life.”

Ted’s downfall was Las Vegas.

The first couple of times he and Christy visited the casinos everything went well: they watched a magic show, they met Elvis. But then Ted had a go on the blackjack tables, and soon he was hooked on the glamour and the adrenaline.

“Before I’d never gambled, but like all the compulsive gamblers in the world, first you throw in a couple of bucks, $10, $20. When time goes by it gets into your blood and you just cannot get it out,” says Ted.

Because he was a high roller the casinos put him up in $2,000-a-night suites and offered him VIP tickets to the best shows.

He began to disappear off to Las Vegas for days, losing $5,000, $7,000 a game, and neglecting his family and his doughnut empire. “I did not have time to take care of business, so business was going down. I did not have time to expand. That’s a disaster,” he says.

Christy would search for him in the casinos, the children in tow. Ted remembers hiding from her behind the slot machines.

Whenever Ted won, the family would rejoice with him. When he lost he would lash out, smashing doors, breaking furniture and frightening the children.

Then he would return to Vegas in an attempt to win back what he had lost. “The more you chase, the more it’s gone,” he says in a new documentary about his rise and fall, called The Donut King. “It’s a devil, it’s a monster. It’s a monster in me.”

Christy always forgave him, but word got around that Ted could no longer be trusted.

“I became a very, very bad man and borrowed money here and there,” he says.

Some of those he borrowed from were the people he had leased doughnut shops to. When he lost their money he would just sign over the shop to them – without telling Christy, whose signature he forged.

Ted did try to curb his habit. He joined Gamblers Anonymous but was back at the tables in no time. “I cry. Everybody cry,” he said. “After cry, go back gambling,” he told one interviewer.

Twice he joined a Buddhist monastery. He shaved his head and spent three months barefoot in Thailand, coming back emaciated and a changed man – or so he thought. But within weeks he was back on a plane to Vegas.

“It’s impossible to explain that money had nothing to do with it. I was addicted to a feeling, and money was simply the needle that delivered the toxic dose,” he writes in his autobiography, also called The Donut King.

Eventually he and Christy were left with just one doughnut shop, which they decided to sell. Their youngest son Chris drove them there to pick up the money – but it went horribly wrong.

Driving back with $85,000 cash in the boot of the car, they were stopped by the police; they had fallen behind with payments, so the car showed up as stolen. All three were taken to the police station but they were too scared to mention the cash in the boot. When they were released, the cash was gone.

“It’s a very very sad story,” says Ted.

In 1993 Ted and Christy moved back to Cambodia. They had lost their beautiful home and their chain of shops, but still had enough money to live comfortably. Ted now had a new passion – politics. Cambodia was having its first democratic elections since the war and he wanted to stand for office to help rebuild his country.

Besides, he reasoned, as a politician he would not be able to gamble. “If I need the vote, I cannot gamble. When people know about the bad reputation, people are not going to vote for me. So I decided to change.”

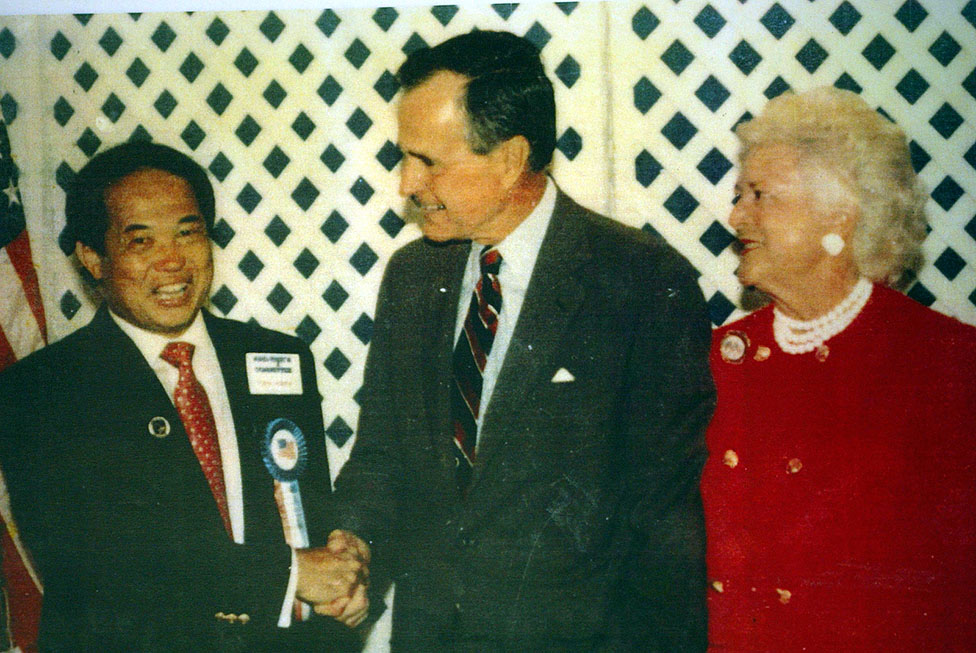

At the height of his success in the US he had been an ardent Republican, and an enthusiastic fundraiser for the party. He had met Richard Nixon, the former president, and Presidents Reagan and George HW Bush. So he named his own political party the Free Development Republican Party.

But the name was misleading. It led many voters to assume, incorrectly, that he was against Cambodia’s royal family, and he didn’t win a seat. He was, however, invited to become a government adviser on commerce and agriculture.

Cambodia was poor and under-developed after years of war. Inspired by the economic success of Taiwan, Ted decided to lobby the US for “most favoured nation” status, which would open the door to foreign investment. “I spent about $100,000 of my own money, my time, my everything,” he says. He lobbied his contacts in the Republican inner circle, including Senator John McCain, and MFN status was granted permanently in 1996.

While Ted was immersed in Cambodian politics, Christy flew to the US for the birth of a grandchild. But while she was gone Ted had an affair. Devastated that he had broken their pact, she filed for divorce.

By 2002 Ted was broke. He had spent all his money on electioneering and on a failed attempt to introduce a new type of hybridised rice, which he believed would improve yields. Then, after falling out with a powerful political rival he feared for his life and fled to the US.

He landed in LA with less than $100 in his pocket – all the money he had left. His family didn’t want to see him, and nobody offered him work, not even baking doughnuts.

He had lost the respect of his family and community. It was a humbling experience, and the lowest point in his life.

“Many times I try to commit suicide because I hate myself. And then I hate the gambling and then I hate that I treat Christy so badly, treat my children so badly, because of the gambling, so I hate myself,” he says.

He moved from church to church, until an elderly Cambodian woman allowed him to live on the covered porch of her mobile home.

“If I need to shower, I knock on the door, ‘Lady can I take a shower?’ And she let me in to take a shower. Then when dinner is ready, she knocks on the door and I open the door to have dinner.”

On Sundays he would go to the church where her son was the pastor and join in Bible studies. Ted became deeply religious.

Still penniless, after nearly four years of exile, Ted flew back to Cambodia. Still homeless, he moved to the coastal town of Kep, on the Gulf of Thailand. He had no way of making a living until a Chinese contact from better days asked him to help out with a real estate deal. Ted negotiated well and got a good commission.

More land deals followed and he has now worked his way back to being a millionaire. He remarried and had four more children – the youngest two are still at school.

Ted kept a low profile until the LA filmmaker Alice Gu got in touch a couple of years ago. A child of immigrants herself, she had become curious why Californian doughnut shops were so often run by Cambodians, and why there were so many of them.

In most of America there’s an average of about one doughnut shop for every 30,000 people – in LA, there’s one for every 7,000 people. And of the 5,000 independent doughnut shops in California today, around 80% are still Cambodian, she says.

“This story sheds light on refugees in a positive way, about what happens when they’re given an opportunity,” she says.

“Ultimately, this is a story of a guy who came to the country with nothing, and with some hustle, and dreams, and a little luck, really made quite a charmed life for himself.”

Which he then threw away.

Alice found it hard to persuade Ted to return to California for filming. He had burned a lot of bridges and at the time his children hardly spoke to him. “He was afraid of being shunned and feeling lonely – but I forced him!” she says.

In the end, filming the documentary was a healing experience for Ted.

Although there is still some resentment towards him in the Cambodian community, whose hard-earned cash he gambled away, he is also revered by many. He enjoyed meeting the younger generation of doughnut makers, who are innovating and inventing new flavours. He also apologised to many of those he hurt.

Most importantly, the trip allowed him to mend relations with Christy, who has now remarried, and with their grown-up children.

“They forgive me fully. I told them I’m very sorry 1,000 times. Every time I met them I said, ‘Sorry son, sorry my daughter, sorry Christy.’

“If you could turn the clock around, I would do that. The past I cannot change, but I learned the heavy way.”

He communicates with them almost every day. “Everybody’s happy to see me now, because I changed from the bad guy to the good guy.”

Ted now sees that the same character traits that made him take bold risks in life also made it easy for him to fall prey to gambling.

“It is the purest form of risk-taking, the distilled anxiety and thrill behind every business decision and bold declaration of love,” he writes in his autobiography.

He credits his Christian faith with finally curing his gambling addiction, although he confesses he liked to bet on football games until last year.

“That’s why I want to tell the world, ‘Do not gamble.’ When you hook up with gambling, your life’s finished. You will end up destroying the whole family and no more relationship with the world, just finished. Gambling is a devil.”

But in the end, he says, he beat it. “I never back down. Never give up. Never surrender. Even in gambling. It took longer than 40 years. But I still win. At the end, I win.”