The Call for Mahama’s Third Term: Will Ghana’s Constitution survive?

The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise with the occasion.” Abraham Lincoln

The discourse surrounding calls for President John Dramani Mahama to contest for a third term has sparked a heated debate across Ghanaian society. Supporters hail the move as an expression of democratic choice, while critics warn of the grave constitutional implications such an attempt could have.

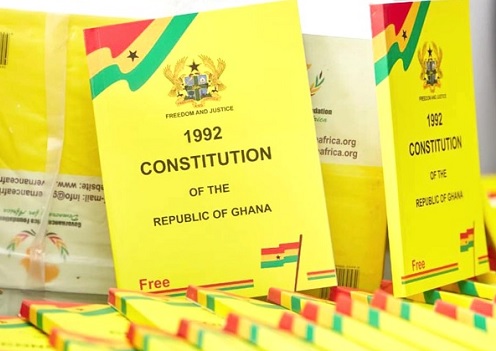

At the heart of this discussion is the 1992 Constitution of Ghana, a document that has long served as the backbone of Ghana’s democratic stability. The question is not merely political. It is fundamentally legal.

Can Ghana allow a two-term president to seek another term without breaching the Constitution? And if such an attempt is entertained, will it signal the weakening, or even death, of the nation’s supreme law?

Article 66(1) of the 1992 Constitution is the linchpin of this debate. The provision explicitly states that “a person shall not be qualified to be elected as President for more than two terms.” The wording is clear, precise, and leaves virtually no room for ambiguity. The drafters of the Constitution intended to establish a firm ceiling on presidential power, a safeguard against the monopolization of authority and the potential slide into authoritarianism.

This principle of limitation is grounded in Ghana’s historical experiences, particularly the periods of military rule and political instability that marked the decades before the return to constitutional governance in 1992. Term limits were designed not to constrain ambition arbitrarily but to protect democracy itself.

Despite this clarity, advocates for President Mahama’s possible third term have attempted to advance arguments that rely on political flexibility and interpretation. They argue that the Constitution should evolve with democratic realities, suggesting that the popular will of the electorate ought to influence eligibility.

Some posit that Article 66(2), which lists qualifications for presidential candidates, could be read in a manner that does not expressly bar a two-term president under certain circumstances. Yet, this reasoning is legally tenuous. Constitutional law is designed to set firm boundaries, and allowing political expediency to override a clearly defined provision would fundamentally weaken the rule of law. Legal scholars widely agree that Article 66(1) represents a non-negotiable limitation, intended to prevent any individual from concentrating power indefinitely.

This debate is not unique to Ghana. Across Africa, attempts to alter or circumvent presidential term limits have frequently led to instability, unrest, and in some cases, violent conflict. Leaders in Uganda, Rwanda, and Côte d’Ivoire, among others, who sought to extend their tenures against constitutional provisions have faced domestic opposition, international criticism, and even civil strife. Ghana’s democratic stability over the past three decades is largely attributable to strict adherence to constitutional norms, particularly presidential term limits.

Deviating from this established order risks setting a dangerous precedent, signaling that laws exist not to guide governance but to serve political convenience.

Any attempt to challenge the two-term limit would inevitably involve Ghana’s judiciary. The Supreme Court, as the ultimate guardian of the Constitution, would play a decisive role in interpreting Article 66(1). Article 1 of the Constitution affirms that the Constitution is the supreme law of Ghana, and any law, custom, or practice inconsistent with it is void.

Consequently, any effort to bypass the two-term restriction, either through legal reinterpretation or political maneuvering, would be prima facie unconstitutional. The judiciary has historically demonstrated its willingness to enforce constitutional limits, particularly in electoral matters, reflecting a commitment to the principles of constitutionalism and separation of powers.

The ethical dimension of this debate is equally critical. Term limits exist not merely as legal technicalities but as moral and democratic safeguards. They prevent the entrenchment of power, encourage leadership renewal, and promote accountability. Circumventing term limits, even under the guise of popular support, undermines the ethical foundation of democratic governance.

Leaders are expected to respect not only the letter of the law but also its spirit. A president who prioritizes personal ambition over constitutional mandates risks eroding public trust and weakening the moral authority of the office.

Ghana’s Constitution already provides a legitimate avenue for amending presidential term limits through Article 290. Such an amendment requires a two-thirds parliamentary majority and a referendum in which at least 40 percent of registered voters approve the change. This process ensures that any alteration of term limits is the product of widespread political consensus and popular support, rather than individual ambition or partisan maneuvering.

Attempting to circumvent this rigorous procedure would constitute a flagrant violation of the Constitution, undermining both its authority and the democratic principles it enshrines.

The political arguments in favor of a third term also invoke voter sovereignty, claiming that the electorate should be free to choose any candidate.

While the principle of voter choice is central to democracy, it cannot override constitutional limits. Ghana’s democracy, like any robust democratic system, depends on a balance between popular will and legal frameworks. Allowing the electorate to elect a leader in contravention of a constitutional provision would essentially place political expediency above the rule of law, threatening the very stability that democratic participation is meant to protect.

Also, the implications of breaching constitutional term limits extend beyond the presidency. It threatens the integrity of other institutions, including the legislature, the judiciary, and civil society organizations that rely on a predictable legal framework to hold government accountable.

A disregard for term limits could create a cascade effect, weaken checks and balances, and erode public confidence in the institutions designed to safeguard democratic governance. Conversely, adherence to Article 66(1) reinforces institutional credibility, strengthens the rule of law, and assures citizens that no individual is above the Constitution.

It is also crucial to consider public perception and international standing. Ghana has been celebrated as a beacon of democracy in West Africa, largely due to its adherence to constitutionalism and the peaceful transfer of power. Any move perceived as undermining term limits could tarnish this reputation, sending a message that Ghanaian democracy is vulnerable to manipulation by political elites.

This would have broader consequences for investor confidence, diplomatic relations, and the nation’s moral authority in advocating for democratic norms on the continent.

The debate over President Mahama’s potential third term is not merely about one individual’s political ambition; it is about the survival of Ghana’s constitutional order. The 1992 Constitution, particularly Article 66(1), is explicit in limiting presidential tenure to two terms. Upholding this provision is essential to maintaining democratic stability, institutional integrity, and the public’s trust in governance.

Any attempt to circumvent these limits, whether through reinterpretation, political pressure, or popular clamor, risks undermining decades of constitutional development. Ghana’s democracy depends on a collective commitment to the rule of law, respect for institutional boundaries, and ethical leadership that prioritizes the national interest above personal ambition.

While calls for Mahama’s third term may reflect political enthusiasm, they confront a clear legal boundary. Ghana’s Constitution is not merely a set of guidelines; it is the foundation upon which the nation’s democratic stability rests.

Article 66(1) leaves no room for ambiguity: no person may serve more than two terms as President. Preserving this provision is not only a legal obligation but a moral and political imperative. Ghana’s democracy, admired for its stability and adherence to constitutional norms, faces a critical test.

The question is not only whether President Mahama can legally contest a third term but whether the nation is willing to protect the Constitution from pressures that threaten its core principles. Upholding the law, defending democratic institutions, and respecting the will of the framers of the Constitution remain essential to ensuring that Ghana’s democracy endures for generations to come.

By: Dominic Ebow Arhin

Political Analyst

Law Student – KAAF University Law School