SPECIAL REPORT: The Okada queen of Accra-The big Okada Debate (Part 2)

Theghanareport.com has since March 2020 undertaken extensive research on this subject to understand the controversies surrounding the illegal use of motorcycles and the status quo of a lax law spurring illegality.

In recent times, the debate has been heightened following the Okada legalisation promise by the opposition candidate, former President Mahama contesting again on the ticket of the National Democratic Congress (NDC) and under whose leadership, it passed the law to out-law Okada business in the election year of 2012.

And rightly so, Ghanaians as typical of us, have been hooked on to the Okada debate with varying opinions for and against Okada business.

In the first part of the Special Report, theghanareport.com explained the dangers in using okada in a series titled the Okada Angels of Death.

In a continuation, the website brings you part 2, explaining why the Okada business is thriving, literally at a breakneck speed.

Why is okada thriving?

A new Royal 125A 2019 motorbike costs averagely GHC3,800 while a Hyundai i10 commonly used for taxis are sold for GHC25,000. The price of the car can buy seven motorbikes.

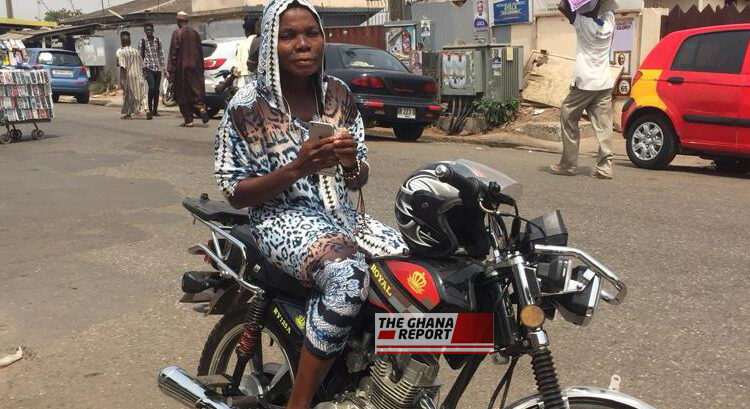

With low maintenance costs, a purely business case for venturing into okada can be made, and that is why 28-year-old, Nafisa Shaibu, popularly known as Kande is the Okada queen of Accra Newton.

READ ALSO: No Ambulance: ‘Okada’ To The Rescue Of ‘Dying’ Woman

She started the business in 2004. She said she was encouraged by a male friend because of the enormous profit potential.

She started with one motorcycle which she gave to a man to work with and render sales to her. After a while, the gentleman also brought his friend to convince Kande to get him one too.

That’s how she got a fleet of eight bikes. She sits back and allows the men to ride around town to make money for the queen.

They render weekly sales of GHC150.

She, however, reduced the number of bikes to five for her current operations and sold three.

She is aware that okada is illegal.

However, she explained, “There is no work in Ghana, and if I was not doing that how am I going to eat?”

The business has not been smooth for her, she acknowledged. Her motorbikes being involved in accidents and impoundments by the police are her primary challenge. And then, some rent the bike to third parties for criminal purposes.

“The rent is the problem because if you give it out, you don’t know what the person is going to do with it.”

Her concern is that “the boys steal too much. They use the motor for the operations”.

“They have done it here before; they sent someone to come and rent the motorbike and used it to go and rob”.

READ ALSO: ‘Legalise Okada’ – NPP MP Backs Mahama

“I’m trying to stop and find another business because if they go and knock somebody or police arrests them, I will pay more than GHC500, and the money that I have will finish. If you are not lucky, it might even take up to a month or two before the police will release the motorcycle,” She lamented.

When Pascal Setsoafia graduated in 2008 from the Koforidua Polytechnic with an HND in Electrical Engineering, he envisaged a professional career like working at a popular cement-manufacturing company.

Eventually, he would become the factory’s head of the electrical engineering department, supervising five other workers between 2009 to 2013.

The company would throw in a two-bedroom flat for him. Everything was fine.

“One day they told me they were giving the apartment to some expatriates so, I have to vacate as they give me a loan to find a new place”.

He said several promises from the company to him were not fulfilled.

“I got seriously sick at a point. That was when I realised they were not paying my SNNIT [contributions]. I got angry; l had also overworked, but I didn’t see my overtime allowances,” he lamented. “My salary by the time was not even up to GHC1000”.

“I realised I had to quit” because colleagues were doing far better as self-employed people.

His first business was an electrical shop, but he was burgled one day. Later, his girlfriend hanged him dry.

“One day, I returned from a trip, and she had packed all my things and bolted.

“This was 2014, somewhere September, she moved everything out, and I had to start my life from scratch”.

READ ALSO: 16 Out Of 20 Accidents Over The Weekend Were From Okada, Ban It Now – Korle Bu Demands

“When the Okada came into the picture was when I realised I didn’t have a choice.”

He bought a bike. Now he says he makes some GHC 3,000 a month.

“In a day I could get GHC100. So GHC 100 times 30, how much is it?”

Pascal Setsoafia says he now has four motorbikes. Two are for his private use while he uses the others for commercial work.

He has employed an Okada rider who renders a weekly sale of GHC 100.

“If someone is paying me GHC 100. It means I am making GHC400 [monthly], and that is from the person alone,” he said.

Pascal is married to a graduate teacher with whom he has a 10-year-old son.

His wife plans to get a Masters’ while Pascal also caters for two sons of a deceased friend and the widow.

A household of nine, surviving on motorbikes in the streets and a teacher in the classroom.

Business is not always brisk, and sales can get very bad, but “Okada has been helpful,” Pascal made no bones about it.

He is now the Chairman for the Aviation Okada Riders Association at Ashaiman.

Pascal doubles as the Coordinator of the Greater Accra Regional Okada Riders Association.

The stories from Ashaiman had different characters but the same plot of how okada is the cornerstone of their livelihoods.

READ ALSO: Okada Riders Are Our Current Headache As 600 Die Annually– Road Safety Authority

Okada riders have various backgrounds with university graduates also partaking in the business.

Sharing a similar story is 52-year-old Alhaji Tijani Umar, who was previously a scrap dealer. But since 2010, Okada business at Ashaiman has been his source of income.

He has four wives and 16 children.

Umar is now the Vice President of the Greater Accra Regional Okada Riders Association.

The profile of Okada riders includes university graduates, returnees such as a man from Libya, disengaged mine workers, and former employees of financial institutions that had collapsed.

“We are pleading with the authorities to legalise okada for us,” Alhaji Tijani Umar noted.

He said strict enforcement of the ban would bring hardships to the more than 20,000 people under the association’s umbrella.

A similar story was shared by Tijani Mohammed, President of the Greater Accra Regional Okada Riders Association.

The sheer numbers of the okada riders mean they can shift the discussion from law enforcement to politics as their aspirations for a change in the law demands a response from power-seeking parties.

Pascal pegs the entire population of okada riders in the country at 800,000.

Okada is seen as the by-product of an inefficient public transport system.

Efficient transport infrastructure and services are the drivers of city systems across the globe, but that is lacking in Ghana.

Currently, only two state firms are providing intracity transport.

READ ALSO: Motorcycle Accidents Spike Road Fatalities For April 2020

The Greater Accra Passenger Transport Executive runs the Aayalolo bus services which exist only in urban areas, mainly Accra.

The Metro Mass Transit Limited, on the other hand, runs intracity, intercity and urban-rural services.

With four million people living in Accra, state-run transport services, private cars, and privately-run transport groups all plying a poorly networked road system creates a stagnant pool of stranded drivers and passengers.

Unlike developed African countries like South Africa, Kenya and Egypt, Ghana has failed to build its railway system to ease the burden on road transport.

Okada advocates have praised okada taxis for their demand responsiveness, traffic decongestion and manoeuvrability through the vast tortuous roads of the country.

The Ghana Private Road Transport Union (GPRTU), an umbrella body for most commercial minibus vehicles (Totro) and, other vehicle operators have been providing services but are unable to meet the demands of commuters in every geographic location.

In some jurisdictions, ‘trotro’ stations do not exist at all, in the case of the Akatsi North District of the Volta Region.

With about 125 communities, not a single commercial vehicle is available, and residents have no choice but okada.

In rural and peri-urban areas, especially the regions up north, where scattered settlements are typical, the motorcycle is the primary transport mode with about 70%-80% use, unlike the south where cars dominate. This is mainly due to the nature of bad roads, which makes it inaccessible for cars.

Statistics at the Driver Vehicle and Licensing Authority (DVLA) shows that there are averagely 10,000 motorcycle and tricycle registrations annually in Tamale alone.

The motorcycle and tricycles also serve as carting equipment for farmers to convey products from the farmgate to the markets and places of need. Besides farmers, nurses and other health workers find them as the most efficient means to access the hinterlands to dispense healthcare services.

For the Head of Education, Research and Training at the Motor Transport and Traffic Directorate (MTTD) of the Ghana Police Service, Superintendent Alexander Obeng, law enforcement officials face a situation where users have suggested that “the disposition of Ghanaians to the use of motorcycles is grounded in reality”.

With an efficient transport system, people are less likely to patronise the high-risk motorcycle taxis.

According to Haruna Abdulai, a Principal Research Technologist at the Savanna Agricultural Research Institute (SARI), a resident of Tamale, owning a motorbike has become a rite of passage for the youth in northern Ghana.

“80% of the youth don’t board Trotro. They use motorcycles. Motorbikes are now like Trotro almost every young guy owns a motorcycle”.

In the Northern Region, women prefer tricycle, he stated.

“They (tricycles) have overtaken the taxis because they are cheaper than a cab,” he explained, adding:” The fare was 50 pesewas when it came first compared to GHC1 to board a taxi”.

The tricycles can take you to any corner, especially for the women who carry loads, but it is not like that with the commercial cars.

Commenting on road accidents, in the north, he said enforcement had shown effectiveness, so the MTTD are stationed at vantage points.

“There is intensive education in mosques and churches,” he added.

Why okada clampdown has been near-impossible

A big challenge confronting the fight against okada is the endorsement of its use by politicians, people in authority and high-profile stakeholders.

Public declarations in favour of okada by officials have encouraged operators to slap the law in the face.

Allegations of people in high authority giving out motorcycles for okada operations are rife even though unconfirmed.

“There are politicians who buy motorbikes for our boys. Even in the security services, people buy motorbikes for the guys,” Coordinator of the Greater Accra Regional Okada Riders Association alleged.

The first people that were against the law were some parliamentarians, the Head of Regulations, Inspection and Compliance at the National Road Safety Authority (NRSA) lamented.

He found it “regrettable” that the then Greater Accra Regional Minister and Member of Parliament (MP) for Kpone-Katamanso, Nii Afotey Agbo, had distributed motorbikes to people in Accra with the explanation of creating employment.

The MTTD of the Ghana Police Service has had their share of the blame as the NRSA official insists, “The police have not put in as much fight to enforce the law”.

Head of the Accident, Emergency and Orthopaedic Department at the KBTH, Dr Frederick Kwarteng also holds the same view.

“The Ghana police service should up their game when it comes to okada riders in Accra. I think they have become too mild with them,” he complained.

But the MTTD have offered reasons why Okada crackdown has been a daunting task for them.

Following the ban, the MTTD deployed countless strategies to ensure enforcement, despite being “laborious and difficult”, Superintendent Obeng explained.

The methods have, however, failed considering the dynamic and complex nature of the situation.

Perhaps the primary challenge of the law enforcement officers is the acquisition of evidence of fare payment from a passenger to an okada rider. Inability to justify commercial against approved private use restrains arrest. Without evidence, offenders cannot be prosecuted, and they go scot-free. At best they are fined, but offenders could still challenge the police in the face of unavailability of proof.

Among the tactics was the roll-out of swoops which the cops still do till date. For example, the MTTD arrested some 23 okada riders, of whom 20 were fined between GHC600 ($252) and GHC1,000 ($420) each in 2013.

A clampdown on February 25 by the Dansoman police resulted in the confiscation of 105 on motorcycles. A similar exercise at Korle Bu resulted in the ceasing of 85 motorbikes and 14 tricycles.

Another way of fighting the menace was sting operations. Police officers would dress in mufti and engage the service of okada operators. The destination would be a location with the presence of a team of other cops to apprehend the rider at the point where the disguised officer attempts payment.

But this “proved very dangerous for the traffic police officer because we anticipated a situation where, in the course of struggle or getting to know that the one behind the pillion is a police officer, the likelihood of dangerous riding can endanger lives,” Superintendent Obeng narrated.

It is also at the benevolence of the one who used the services to own up and admit that he or she is a fare-paying passenger, he disclosed.

However, he maintained, “If we get evidence, we will then proceed to court”.

This leaves the police focusing on safety issues of riders rather than concentration on Okada enforcement.

“It looks as if the police is overwhelmed at his duty point,” Superintendent Obeng noted. “We are in for an emerging phenomenon which goes beyond traffic policing to a national security issue.”

His men/women, therefore, look for private motorcycle registration, the licence of the rider, motorcycle insurance and use of protective gear (riding suit, helmet etc.).

Bloody clashes between Okada operators and law enforcement agencies have emerged, leading to death, in some instances.

Dr Martin Oteng-Ababio, the Head of Department of Geography and Resource Development at the University of Ghana and his colleague Ernest Agyemang, a Senior Lecturer from the same department suggested in a research published in the African Studies Quarterly journal in September 2015, that:

“frustrated by the failure of policymakers to seek their consent, okada operators and their cohorts have defiantly pledged to protect their turf (i.e. livelihoods) where national-level inaction has typically prevailed.”

What they described five years ago in their paper has been more pronounced in recent times. Perhaps they foresaw the clashes at Ashaiman between okada riders and police which led to the firing of warning shots and destruction of a police vehicle on February 24, 2018. The riders pelted cops with stones injuring the Ashaiman police commander in the process over what they said were arbitrary arrests, harassment and illegal fines.

The most recent is the death of one person on September 29, 2019, at Senchi in the Asuogyaman District of the Eastern Region as police fired warning shots in an attempt to disperse a group of riders. The okada operators had besieged a police station to demand the release of two of their colleagues who had been arrested.

According to Member of Parliament (MP) for Asawase, Alhaji Mohammed-Mubarak Muntaka, the police in his constituency have said that their cells would not be able to contain the number of okada culprits if they go ahead to effect arrests to the letter.

Additionally, the police station does not have enough spaces for all the cycles that would be impounded.

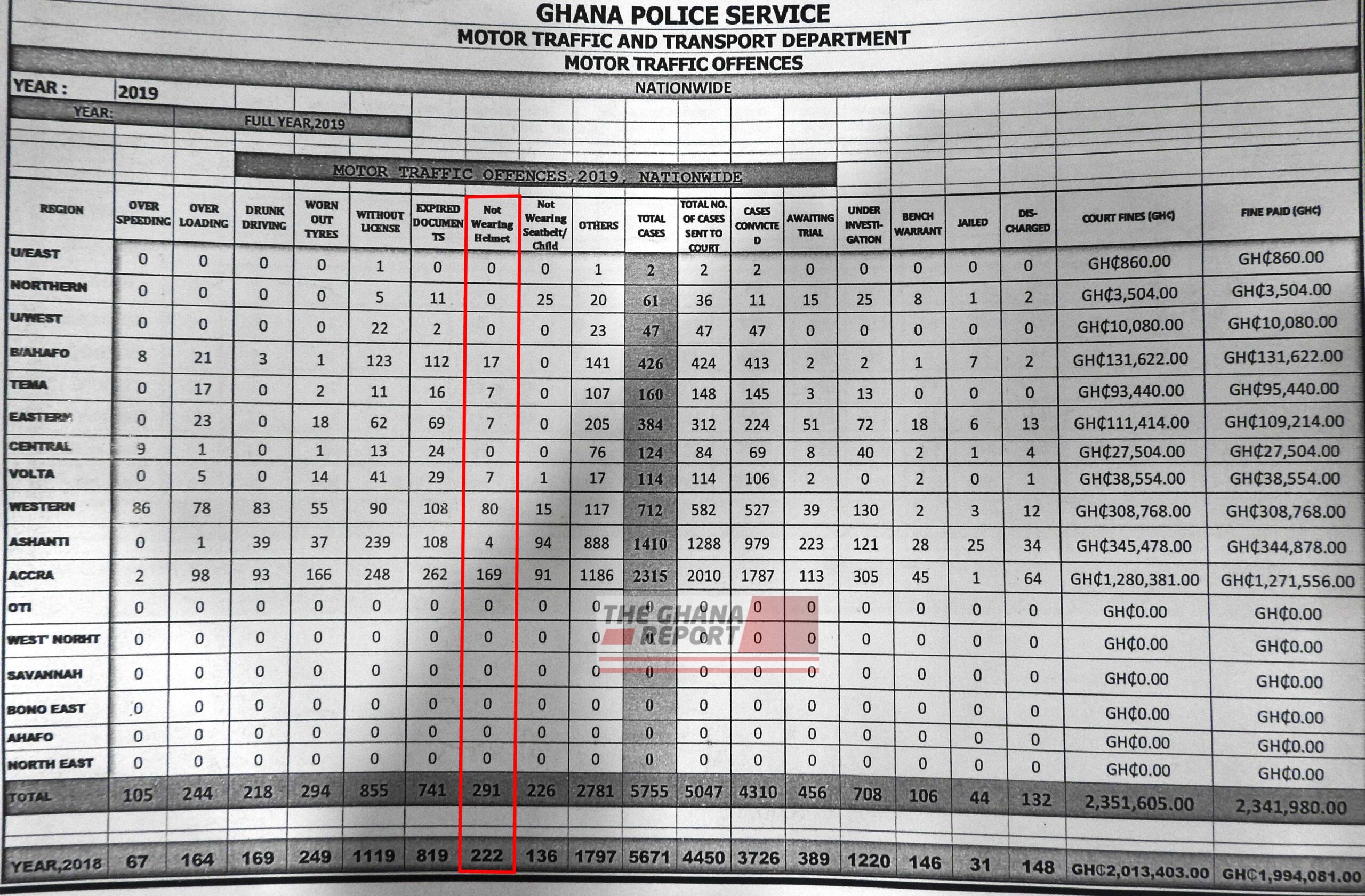

The table below captures sanctions meted out to road traffic offenders in 2019.

It appears enforcing the law could trigger massive resistance from Okada riders, a business constituency that is fast becoming a political constituency.

A lax enforcement regime also raises questions about the usefulness of a law that does not often bite and entrenches the call for legalisation and regulation subtly.

But what do the law-makers think? Have those who pushed for the legalisation changed positions and vice-versa? Is there a bi-partisan agreement in parliament over the legalisation of okada? Are NDC and NPP MPs agreeing in smaller groups while the official positions mark disagreements? What is the way forward for Ghana?

In the third and final part of this SPECIAL REPORT, theghanareport.com provides answers.

Great Work done producing a great piece. THANKS Sir!

Informative! I enjoyed reading it as well.