For most university students in Ghana, funding their education is an uphill battle. The average tuition fee is pegged at GH₵3,000, while skyrocketing hostel fees can reach as high as GH₵16,000 annually.

Combined with the rising cost of living, higher education in this part of the world is increasingly inaccessible to the less privileged.

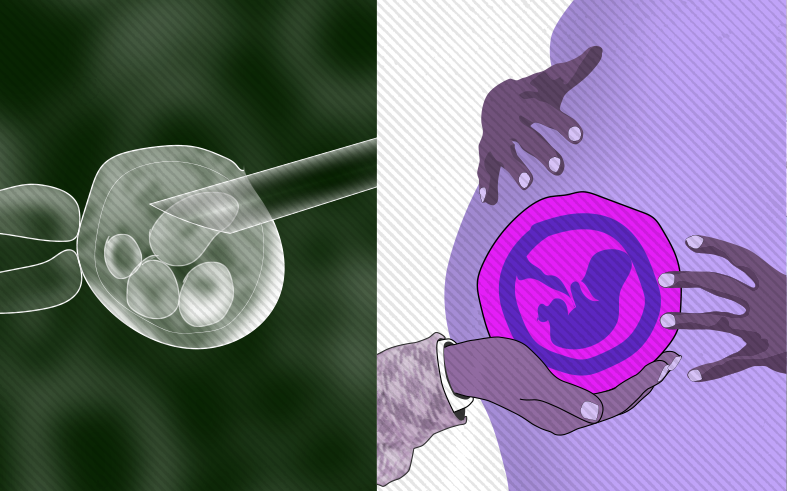

For 25-year-old Abena Mensah (not her real name), achieving her dream of becoming a journalist required more than just meager student loans or part-time jobs with paltry pay. To complete her four-year journalism degree at the University of Media, Arts, and Communication (UniMAC-IJ), she made a sacrifice many would find unimaginable—donating her eggs for three years to finance her education.

A dream born in modesty

Abena was born into a modest family in Kumasi. From a young age, she knew journalism was her calling. As a child, she would stand in front of a mirror, mimicking newsreaders and crafting imaginary reports with the conviction of a seasoned journalist. However, when she gained admission to UniMAC-IJ in 2020, her dream collided with the harsh reality that she had no means to pay for it.

“I had no financial support. My mother was a petty trader, and my father had passed away when I was eight. There was no way I could afford university,” she recalled.

Determined to make it work, Abena tried everything. She borrowed from friends, took out loans, and worked multiple jobs.

“I applied for a student loan after struggling to pay my first-year fees. With my mother’s help, borrowing from MTN Quick Loan, and contributions from three friends, I managed to raise GH₵3,000. My tuition alone consumed everything, leaving nothing for accommodation.”

To survive, she took on a part-time job as a Mobile Money (MoMo) vendor at Tema Station, earning GH₵600 a month. But the job took a toll on her academics.

“I couldn’t attend midday lectures. My schedule was tight—I’d go to my 7 am to 9 am class, rush to work, and return for evening lectures from 6 pm to 8 pm. Even with all that, I couldn’t cover all my courses. I was missing out.”

Juggling work and studies was exhausting, and she still couldn’t raise enough money to pay back her debts, let alone take care of herself. Then, while researching for an assignment, she stumbled upon an article about egg and sperm donation and how young people were turning to it for financial relief.

“When I saw that, I knew there was another option to explore. So, I embarked on a journey to find a fertility clinic willing to harvest my eggs and compensate me. That’s how you met me at the hospital,” she told The Ghana Report journalist Edinam Sablah.

The decision to donate

The idea of egg donation initially seemed absurd to Abena. Could she really part with something so intimate? Would it affect her health? But desperation has a way of pushing boundaries. After thorough research and consultations, she decided to proceed.

In 2021, she walked into a fertility center in Taifa, Accra.

“I enquired about the procedure and how much I’d be compensated. They explained that I had to undergo tests before I could donate. For every donation, I would receive GH₵3,000 and an additional GH₵150 for transport each time I had an appointment. They even had hostels for those without a place to stay but wanted to donate monthly.”

However, GH₵3,000 per donation (approximately $190) is a fraction of what egg donors receive in many parts of the world. In countries like the United States, donors can earn between $5,000 and $10,000 per cycle. Yet, in Ghana, this life-altering decision was worth little more than a semester’s rent.

At first, Abena didn’t dwell too deeply on the decision.

“I just felt this would solve all my financial problems at the time.”

The clinic preferred donors who had already given birth, citing psychological reasons. But Abena convinced them otherwise.

“I assured the medical officer that I was okay with my decision.”

She was also informed that she could donate a maximum of six times a year for medical reasons.

The emotional and physical toll

For three years, Abena donated her eggs, sometimes thrice a year. The process was painful, both physically and emotionally, but each donation paid for her tuition, books, and sometimes even her meals.

Her decision wasn’t without condemnation. Some friends distanced themselves, whispering that she was “selling her body.” But Abena saw it differently.

“I wasn’t selling my body. I was investing in my future. My eggs weren’t my identity—my mind, my voice, and my passion for storytelling were,” she said.

Yet, as the years passed, the weight of her decision began to settle in.

“Recently, I’ve struggled with my mental health. Whenever I remember the number of times I’ve donated my eggs, I start to think that I might have dozens of biological children somewhere in the world. Even though I haven’t had a child of my own yet, it’s mentally draining. I wouldn’t say I regret this decision, but sometimes I wish I had another option,” she confessed.

A journalist with a mission

Today, Abena has graduated and is practicing as a journalist at one of Ghana’s reputable media houses. She reports on student struggles, women’s health, and economic hardship—stories that hit close to home.

Her ultimate goal is to become an investigative journalist, exposing the struggles of young women who, like her, have had to make tough choices for a better future.

“When I hold my journalism degree, I’ll know it wasn’t just handed to me—I earned it, one sacrifice at a time.”

Through her work, Abena hopes to amplify the voices of those who, like her, have had to pay a high price for their aspirations—and to inspire change for future generations.