Second new coronavirus variant worries health experts. Here’s what we know

Another coronavirus variant that shares some of the same mutations as the B.1.1.7 strain, first identified in the U.K., has begun spreading rapidly after it was first identifiedin South Africa in mid-December.

It has quickly become the predominant variant there, but it has also gained a foothold in other countries, including Brazil, which is experiencing a surge of COVID-19 cases.

The new strain, designated 501Y.V2, emerged independently from the U.K. variant, but they both share a few mutations in common, including one that seems to make both these variants more infectious. However, there’s no evidence yet suggesting that they cause more severe disease.

So far, the South African variant has not been detected in the U.S., but top infectious disease expert Dr. Anthony Fauci told Newsweek that he would be surprised if it were not already here, noting that because of international travel, “sooner or later viruses spread throughout the world.”

There have already been a number of new coronavirus strains identified since the start of the pandemic. Mutations are a natural process in a virus’s life cycle, and these changes are not always significant. However, monitoring these changes is crucial to stay one step ahead of the virus and fight it effectively.

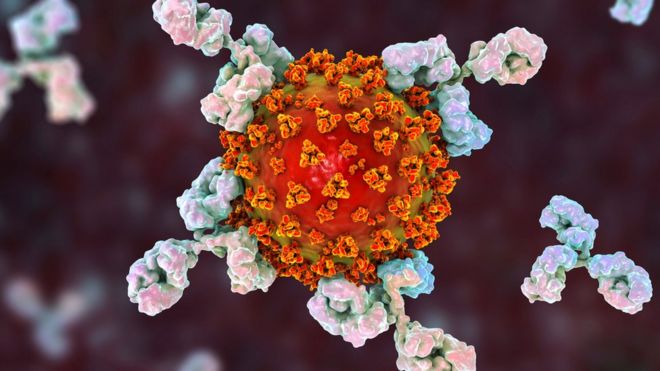

There is a lot that is not yet known about the 501Y.V2 strain, but there are a few reasons why it is worrying experts. The new variant carries three mutations in key sites in the receptor-binding domain of the spike protein, which is the “key” the virus uses to gain entry into cells. Some of these changes, especially a mutation called E484K, have been shown to reduce antibody recognition. In other words, the change could make people’s antibodies less effective at neutralizing the virus. This mutation is gaining attention because it may help the virus slip past immune protection from prior infection, as well as from some of the antibody therapeutics being used in the treatment and possibly vaccination, though scientists are still trying to test these hypotheses.

Scientists are racing to investigate the significance of these mutations as it relates to vaccine efficacy, but they believe that the current mRNA vaccines will continue to be effective against the known new variants. This is because vaccines such as those from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna were developed to create antibodies to multiple regions of the virus’s spike protein.

“A single mutation is never enough to get away from a vaccine. When you get vaccinated, your body produces like a thousand different antibodies … so maybe that single mutation might cause you to lose one or two or five of those antibodies. They won’t work as well anymore.

“They’ll bind weakly and fall off, or they don’t recognize the virus at all, but you’re going to have others that are working just fine,” said Jacob Glanville, founder and CEO of Centivax, a computational immuno-engineering group that focuses on making antibody therapeutics and vaccines.

Glanville’s company is currently working on the development of two different types of antibody therapeutic therapies against COVID-19. He told Yahoo News that the mutations in the receptor-binding domain of the spike protein are more concerning for some of the current antibody drugs than they are for vaccines.

“That’s a concern for antibody therapeutics because if the antibodies are trying to block that interaction, they’re going to be right on the spot where the mutations are,” he added.

As immunity rises in the population, either by vaccination or infection, the virus will naturally continue to change. But scientists are confident that as the virus adapts, we will also be able to adapt, by modifying our vaccines. Fortunately, that process so far seems to be relatively easy.

“They would slightly modify the genetic sequence. So it would be the same vaccine. It would just be slightly different genetic information. It’s literally using RNA, which you can alter, and it’s a very clean, simple molecule, so they can process it relatively quickly.” Glanville told Yahoo News.

It remains unclear whether these updated vaccines will require new clinical trials, as they did this year, but Glanville said the process that has been put in place to update new flu vaccines every year may give us a clue as to how that could work with COVID-19 vaccines.

“There are a series of expedited processes that have been set in place for decades. … Every year [scientists and vaccine developers] say, ‘Listen, the new flu is going to pop up. It’s different enough that we need a new version, but it’s basically the same flu shot. We’re just tweaking it.’ And so that allows them to do this extra-fast approach of being able to estimate what they should probably put in that vaccine to provide people the best possible coverage … but because you’re producing basically the same vaccine, but with some modifications, you don’t have to go through all those phase trials.”

He added, however, that it is too soon to know exactly how this will pan out with COVID-19 vaccines, especially because they are new, but he has confidence that the technology behind the vaccines will make things relatively straightforward.

“I think the things that are going to slow you down are not so much the technologies at this point; it’s going to be the regulatory hurdles,” Glanville said. “There’s going to be a calculated balance, and it may depend on nation to nation on what level of expedited updating to the vaccines that they’re willing to tolerate.”