A novel UK satellite has returned its first pictures of heat variations across the surface of the Earth.

HotSat-1 carries the highest resolution commercial thermal sensor in orbit, enabling it to trace hot and cold features as small as 3.5m across.

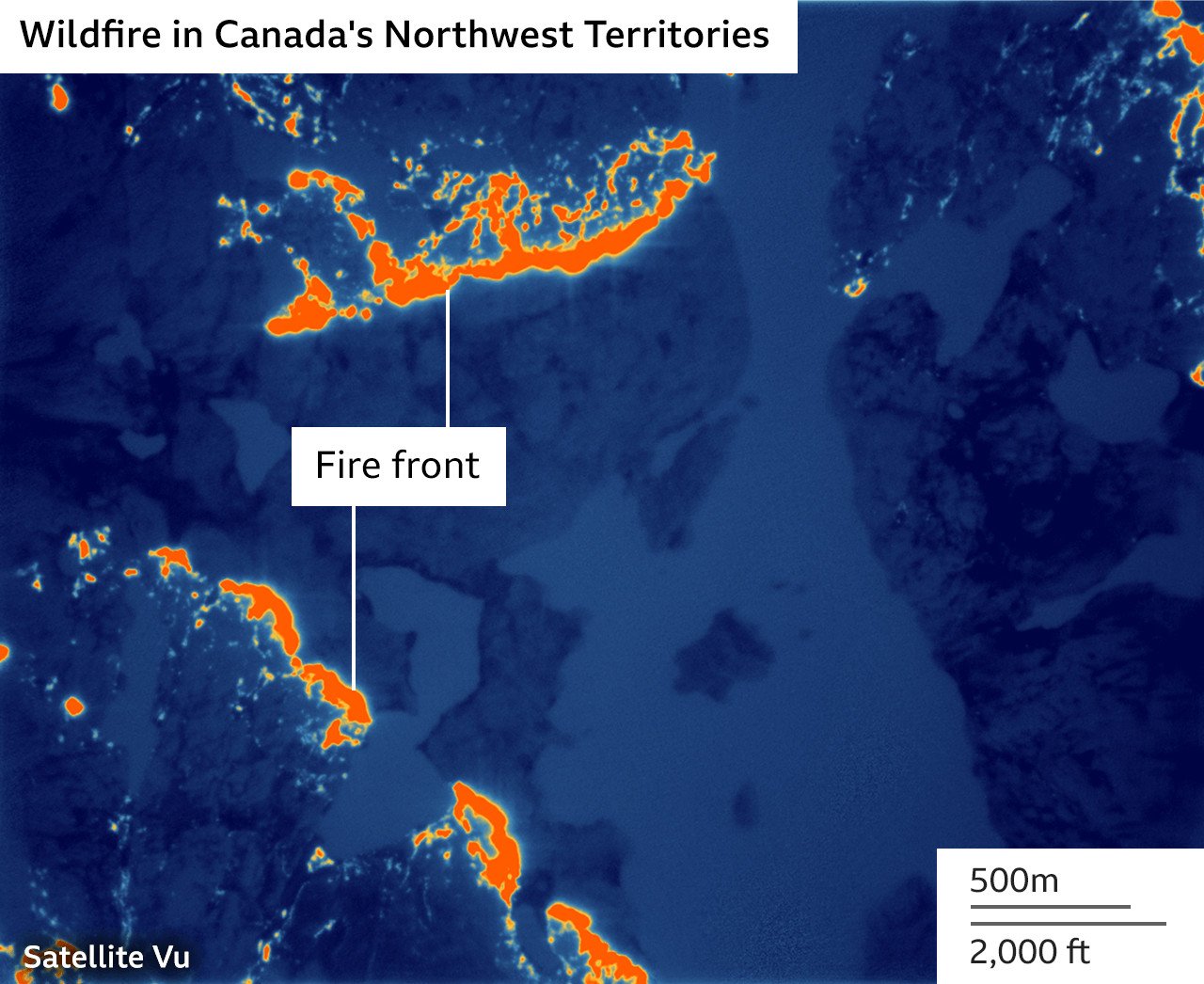

In the initial imagery, a Chicago train is observed moving through the night and the flame fronts of Canadian wildfires are precisely mapped.

London operator SatVu plans to launch seven additional spacecraft.

This will increase the volume of data it can acquire but also reduce the time between passes over particular locations, meaning changes in a scene can be detected more rapidly.

HotSat-1, with its mid-wave infrared camera, was assembled by Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd (SSTL) in Guildford and launched in June on a SpaceX rocket flying out of California.

“At that point ‘we get the keys’, so to speak, and we’ll then be able to task the satellite ourselves and get the data down for our customers,” Tobias Reinicke, the chief technology officer at SatVu, told BBC News.

HotSat-1’s heat maps – still imagery and short videos – should have wide application, but especially in climate-related matters.

They’ll permit urban planners, for example, to see roof tops and walls. This will enable them to understand the temperature profiles of individual buildings, offices and factories. It’s information that can identify infrastructure that’s wasting energy and is in need of better insulation.

“We’ve got 28 million homes in the UK, most of which are quite poorly insulated,” commented Prof Emily Shuckburgh.

“Being able to identify those buildings with this sort of information, prioritising them for better insulation and then assessing the quality of that is really, really important,” the director of Cambridge Zero, the University of Cambridge’s climate change initiative, said.

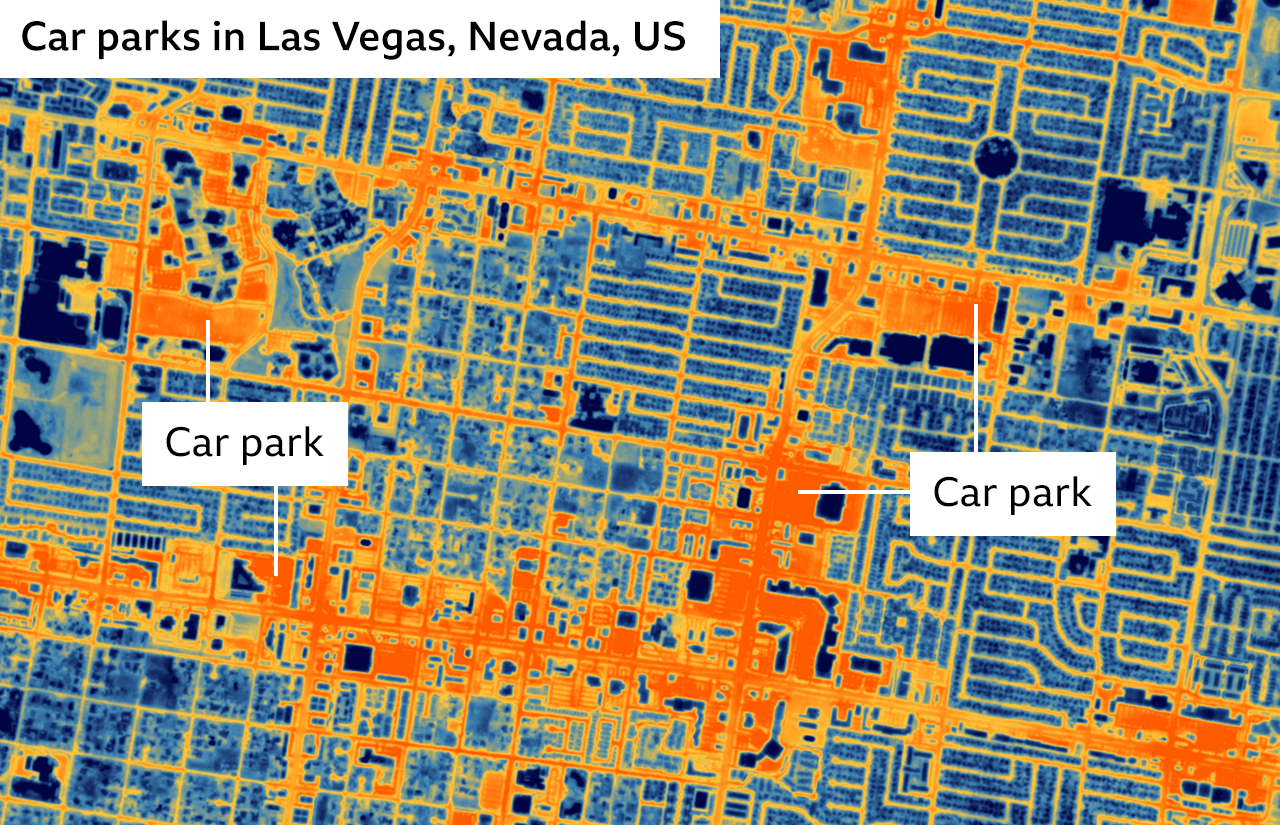

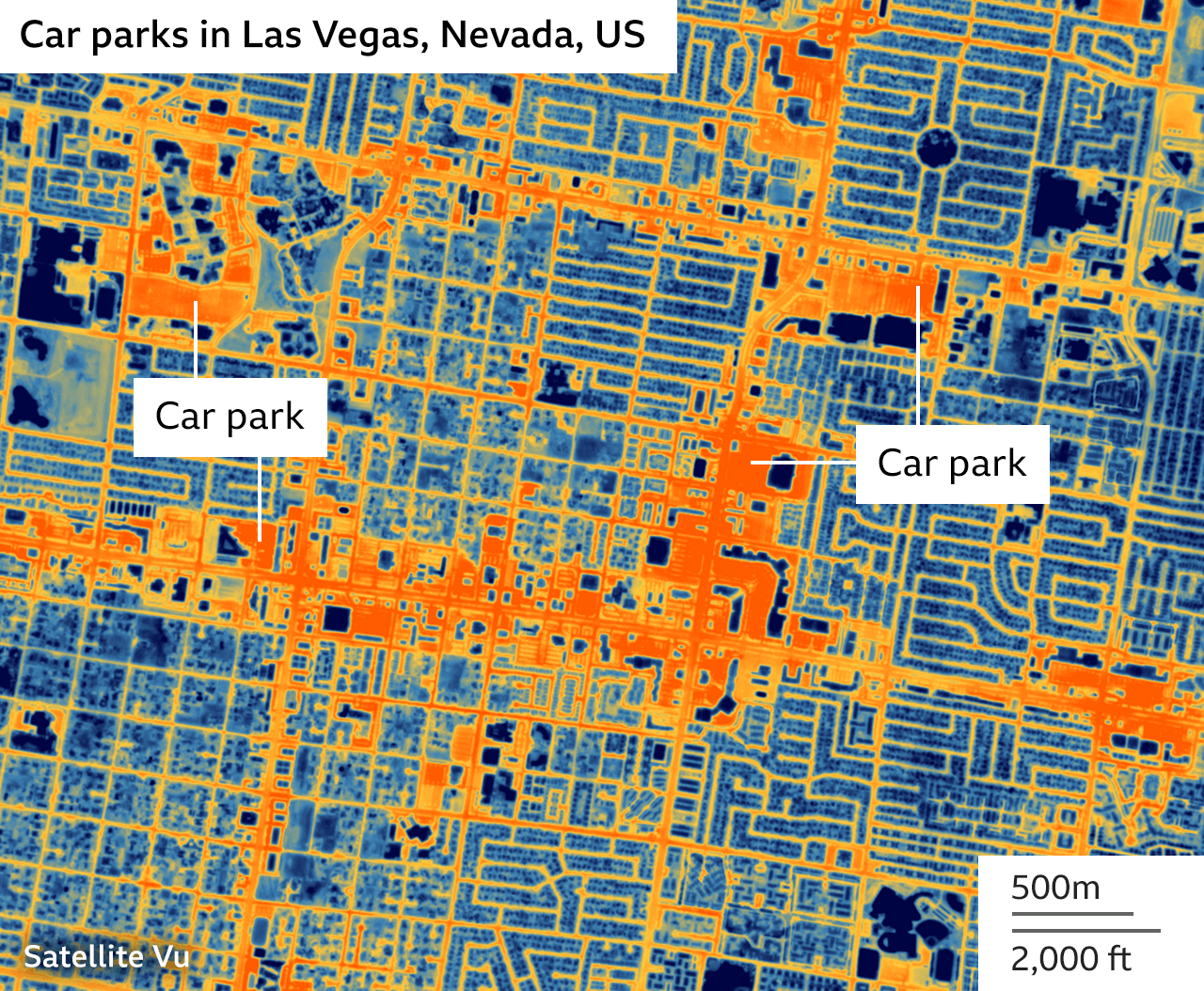

Alternatively, the maps will show the “heat islands”, such as large, open car parks, which add to the heat stress in cities and will need to be cooled, perhaps with a line of trees.

The data is also sure to provide intelligence to the financial and insurance sectors – and even the military – by revealing how temperatures in a scene change over time. It’s possible, for example, to get a sense of the volume and type of output from a factory just from its heat signature.

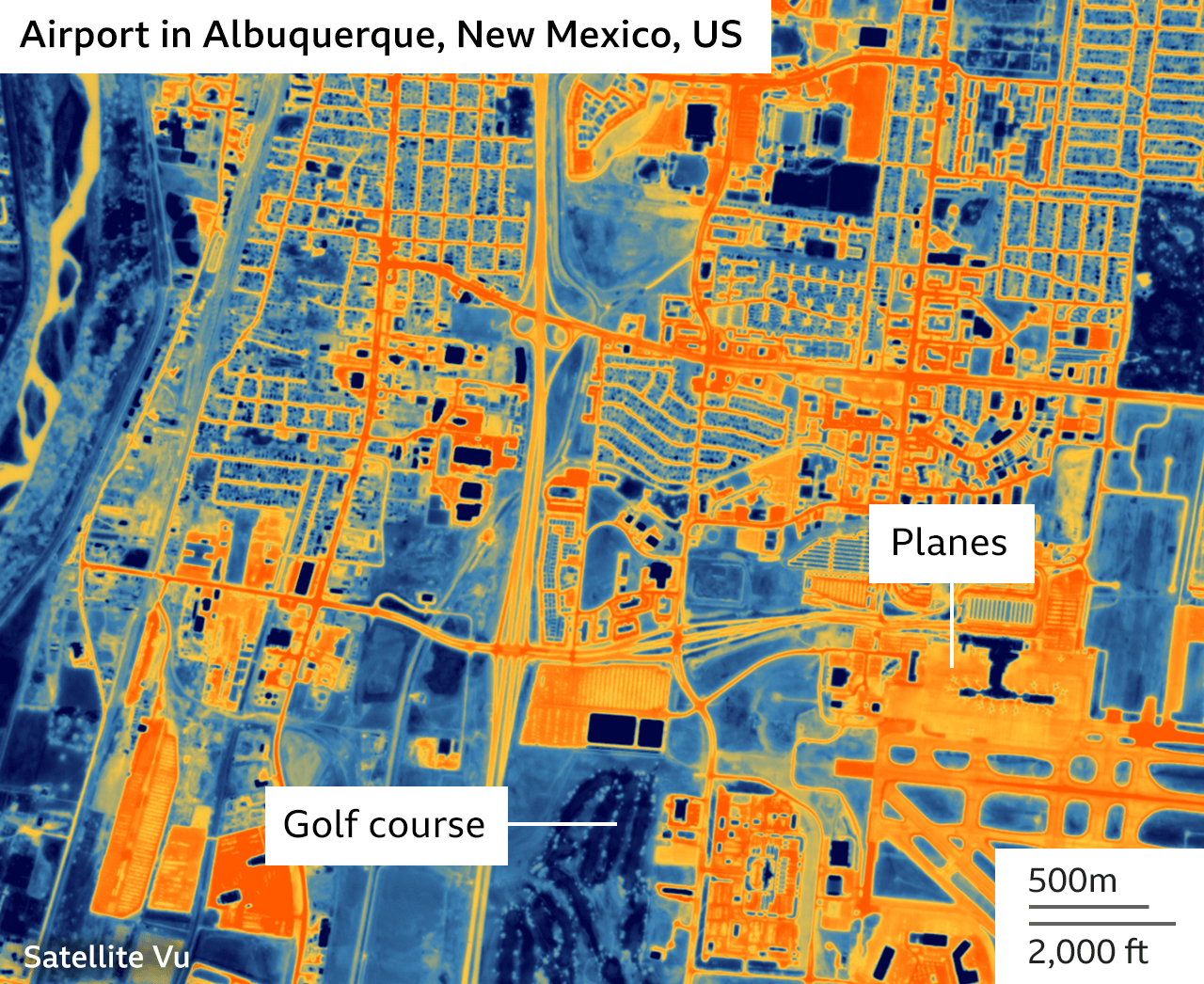

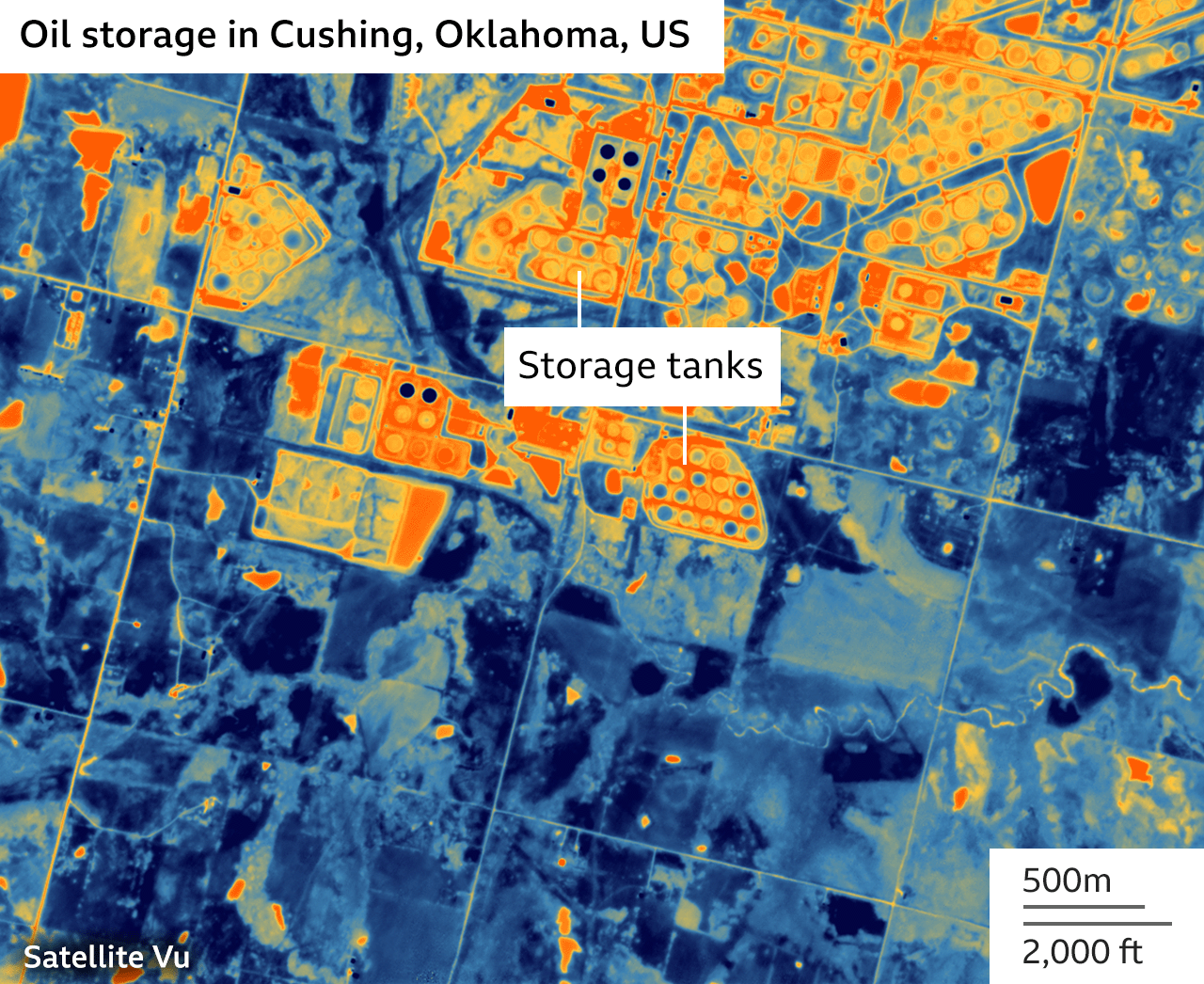

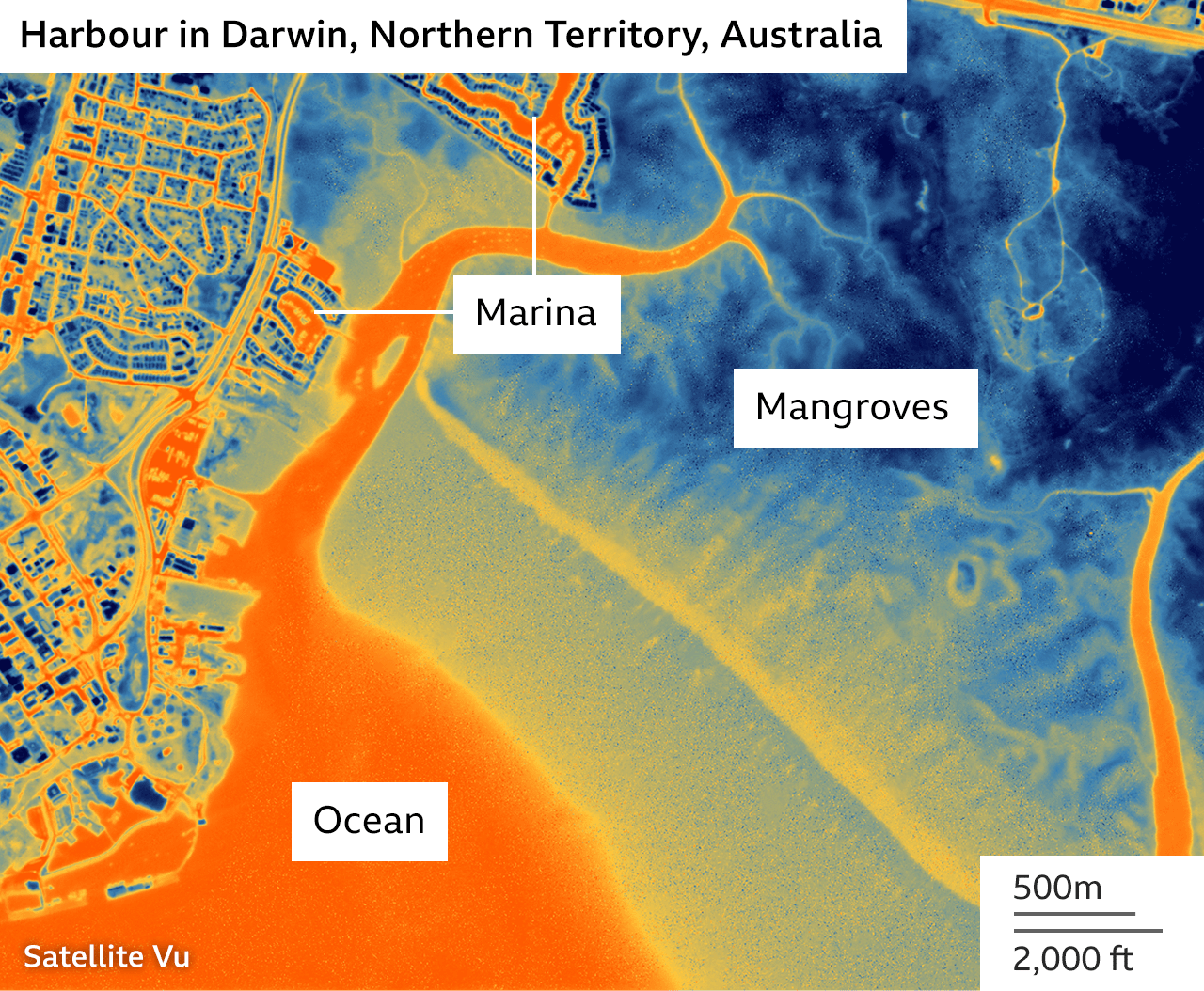

In the imagery on this page – the redder the colour, the warmer the surface; the bluer the colour, the cooler it is.

Las Vegas, Nevada, US: See how the tarmac and concrete in roads and parking zones builds heat during the day to then slowly release it at night. This retained energy will make hot nights even more uncomfortable for residents.

Albuquerque, New Mexico, US: Look at the airport. You can count the number of planes around the terminal. A standard optical satellite, which views the ground in light similar to what our eyes sense, cannot see this night-time detail.

Cushing, Oklahoma, US: Companies wanting to know how much oil is moving through storage depots will fly remote-sensing drones to gather intelligence. But regular satellite overflights can gather this data far more efficiently and be global in view.

Northwest Territories, Canada: This image acquired on 27 July shows the active fronts of wildfires. A video of the scene could be used to help predict the speed of fire progression and the potential paths of impact.

SatVu had pre-launch commitments worth £100m from users who plan to use the thermal data – both within the UK and internationally.

About 60 entities are part of an early access programme and will now get to play with imagery to determine whether it meets their requirements.

The technology in HotSat-1 was funded with R&D money from the UK and European space agencies (UKSA & Esa).

Independent remote-sensing expert Dr Simon Proud commented: “The prospects of HotSat-1 for urban planning and agriculture are exciting. But we need to assess how accurate the data is, especially during the day when the satellite sees sunlight on top of the actual temperature.

“It’s also key to have stable measurements over time – essential for monitoring the success of interventions like adding roof insulation to a house or trees to a car park,” the RAL Space and National Centre for Earth Observation scientist told BBC News.