Nuzo Onoh – the Queen of African horror who is terrified of ghosts

Known to her fans as the “Queen of African Horror”, British-Nigerian author Nuzo Onoh says her prestigious literary prize is a signal that African folk horror has finally become an internationally recognised genre.

“When I started writing, if you googled ‘African horror’, what you would get was Aids, war, famine. But now you’ll get books, films. They are part of the literary genre pool,” she tells the BBC’s Focus on Africa.

Onoh formally received the Bram Stoker Lifetime Achievement Award from the Horror Writers Association (HWA) in June. It described her as “a pioneer of the African horror literary genre [whose] writing showcases both the beauty and the horrific in the African culture”.

Previous winners of the award include household names in horror fiction like Stephen King, Anne Rice and British actor Christopher Lee, famous for playing Dracula in numerous films.

Born in Enugu in south-eastern Nigeria, Onoh comes from the Igbo community.

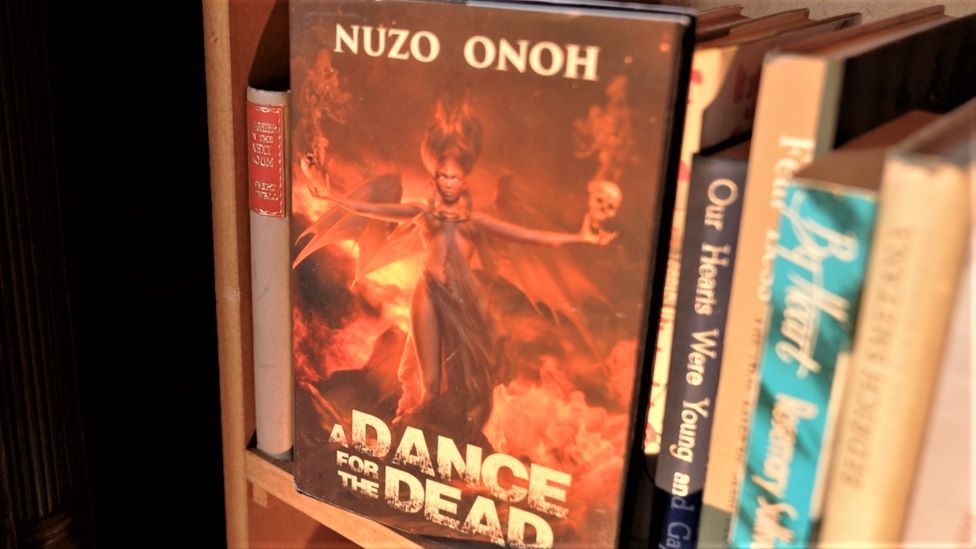

Her most recent book, A Dance for the Dead, draws heavily from Igbo culture and traditions.

It follows the journey to redemption of character Diké, first son of the fictional king of Ukari and heir to the throne.

Diké is tragically cast as an “Osu” – an outcast – after he is found in mysterious circumstances within the sacred shrine of the village god.

In Igbo tradition, Osus were people who ran into the shrines of deities to seek protection from threats from other community members.

Anyone who ran into such a shrine would no longer be troubled, but at the cost of becoming an Osu – someone who’d dedicate their whole life to worshipping the deity while at the same time being an outcast in their community.

Their new condition would prevent them and their offspring taking chieftaincy titles or marrying a freeborn.

“Outcasts exist in every society, when you think about the outcasts of racism, of classism here in the UK,” Onoh says.

“But some countries have taken things further. To create a caste of people that are excluded and made out to be inferior.”

Although Nigeria passed a law in 1956 that banned the practice of referring to people as Osu, some people still do it.

Up to today, a marriage can be cancelled at the last minute if one of the partners finds out that the other is an Osu, or a descendent of one.

“It’s a cultural thing,” Onoh says “in my village we had ones called ‘Ofu’, and those ones are slaves to man, not to gods. They are not allowed to go to the village stream and they can’t take titles.”

Her father, who served a short term as governor of Nigeria’s south-eastern Anambra State before being ousted in 1983 by then-military ruler Muhammadu Buhari, opposed the Osu practice.

In A Dance for the Dead, Onoh also condemns the discrimination of people living with albinism and the use of interclan violence.

The hero, Diké, has to withstand terrifying ordeals before being accepted in the realm of his ancestors.

He survives torture inflicted by creatures belonging to a persecuted community of people living with albinism and endures the vendetta of a clan that his dad – the king – formerly oppressed.

“Black people are discriminated against because of the colour of their dark skin [but] back home they are discriminated against because of the colour of their pale skin, and the worst part is that they fear for their life because their body parts are harvested,” Onoh says.

She also admits that she adds her own spin to traditional practices to spotlight the role of strong women.

In the novel, Diké is surprised to find out that the ancestors who helped him undo his curse are all women.

“It’s a creative licence. Growing up, the ancestors we would worship were all men. So, I decided to make them women this time,” she tells the BBC.

But promoting culture through the lens of the horror genre can also cause misunderstandings. She says some critics back home have described her work as “satanic”.

Her previous books – The Unclean, The Reluctant Dead and Dead Corpse – reveal Onoh’s profound interest in the relationship between the living and the dead.

But it’s not only about narrative fiction.

In 2017, she published a self-help book, Call Your Ancestors For Success and Happiness, where she gives practical advice on how to worship one’s ancestors, and departs from tradition by combining Igbo rituals and personal practice.

Onoh believes young Nigerians are increasingly interested in reconnecting with their traditions.

“I get emails from people asking me how do you do it? After the Black Lives Matter movement there seem to be this switch. You find a lot of young people now going back to the original traditional religion,” she says.

“It’s like this spiritual movement of everybody trying to reconnect once again with their roots through the ancestors.”

In one of the anecdotes, she tells how reflecting on a dream she had about her deceased mother saved her from a potentially lethal electrocution while mowing the garden.

Onoh also believes that the spirit of her mother is behind her recent award.

“It’s her blessing. The day that I was officially given the Bram Stoker award happened to be the same day my mother had died [seven years earlier]”.

Now in her early 60s, Onoh has developed an idiosyncratic relationship with the horror genre.

“I am terrified of ghosts and darkness. I still sleep with a bright light on. I can’t sleep without [it],” she says.

“As I grow older, I found that I struggle to watch horror films or read horror books,” Onoh says, while admitting that “it’s my natural thing to write horror. I don’t know why.”

She believes it’s a way to process the real-life horrors she witnessed growing up during the Biafran war between 1967 and 1970.

Conflict broke out after an Igbo general declared the breakaway state of Biafra. The military crushed the secessionist movement, with about a million people dying from famine, disease and fighting.

Onoh was a child refugee in various towns and villages until the war ended. Then as a teenager she moved to the UK to study in a Quaker boarding school for girls.

“When I write it’s like a form of exorcism,” she says. “We grew up during the Biafran war, surrounded by a lot of death. You sort of have this morbid fascination with everything horror,” she says.

Onoh’s forthcoming book, The Ghosts in the Moon, is an intergenerational tale looking at how traditional magic is passed down through women of the same family. It is due to be published next year.

She holds a Masters degree in Writing from the UK’s Warwick University, but says she doesn’t use much of the skills learnt on the course, favouring a non-structured and spontaneous approach.

“I don’t do plots. I don’t do structure. The characters come into my head and they start dictating, and I’m just writing,” Onoh says.