Norway to approve controversial deep-sea mining

Norway is likely to become the first country in the world to move forward with the controversial practice of commercial-scale deep-sea mining.

The plan, up before a parliamentary vote on Tuesday, will accelerate the hunt for precious metals which are in high demand for green technologies.

Environmental scientists have warned it could be devastating for marine life.

The vote concerns Norwegian waters, but agreement on mining in international waters could also be reached this year.

The vote is expected to pass without hindrance after it secured cross-party backing at the end of 2023.

The Norwegian government said it was being cautious and would only begin issuing licences once further environmental studies were carried out.

The deep sea hosts potato-sized rocks called nodules and crusts which contain minerals such as lithium, scandium and cobalt, critical for clean technologies, including in batteries.

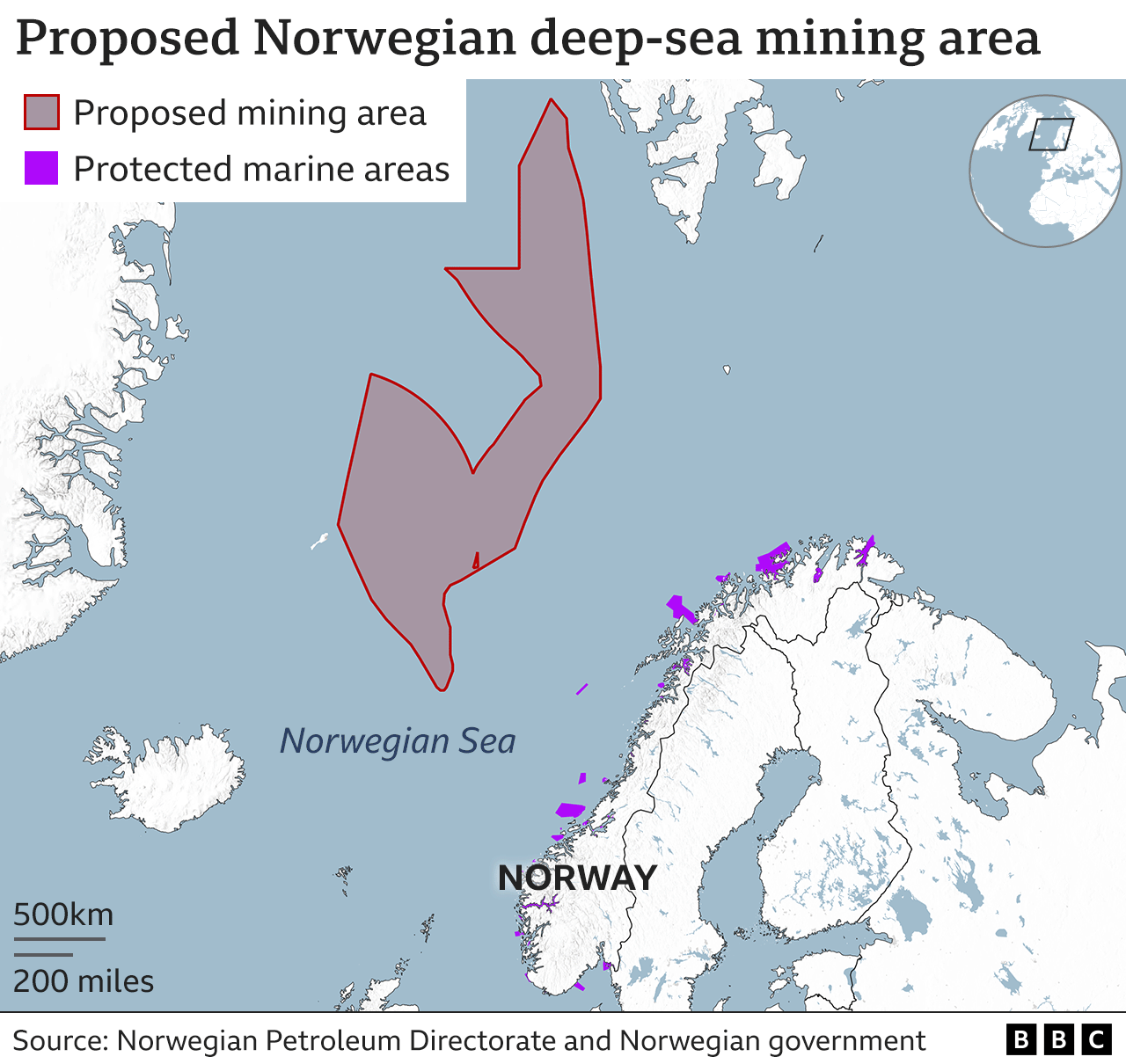

Norway’s proposal will open up 280,000 sq km (108,000 sq miles) of its national waters for companies to apply to mine these sources – an area bigger than the size of the UK.

Although these minerals are available on land, they are concentrated in a few countries, increasing the risk to supply. For example, the Democratic Republic of Congo, which holds some of the largest reserves of cobalt, faces conflict in parts of the country.

Walter Sognnes, co-founder of Norwegian mining company Loke Minerals, which plans to apply for a licence once the proposal is passed, recognised that more needs to be done to understand the deep ocean before mining begins.

He told the BBC: “We will have a relatively long period of exploration and mapping activity to close the knowledge gap on the environmental impact.”

Martin Webeler, oceans campaigner and researcher at the Environmental Justice Foundation, said it would be “catastrophic” for the ocean habitat.

“The Norwegian government always highlighted that they want to implement the highest environmental standards,” he said. “That is hypocritical whilst you are throwing away all the scientific advice.”

He said that mining companies should focus on preventing environmental damage in current operations, rather than opening up a whole new industry.

Image caption,

The proposal puts the country at odds with the EU and the UK, which have called for a temporary ban on the practice because of concerns about environmental damage.

Techniques to harvest the minerals from the sea floor could generate significant noise and light pollution, as well as damage to the habitat of organisms relying on the nodules, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

In November, in an unusual move, 120 EU lawmakers wrote an open letter calling on the Norwegian parliament to reject the project because of “the risk of such activity to marine biodiversity and the acceleration of climate change”. The letter also said the impact assessment conducted by Norway had too many knowledge gaps.

As well as external criticism, the Norwegian government has also faced pushback from its own experts. The Norway Institute of Marine Research (IMR) said that the government had made assumptions from a small area of research and applied it to the whole area planned for drilling. It estimates a further five to 10 years of research into impacts on species is needed.

The Norwegian government will not immediately allow companies to start drilling. They will have to submit proposals, including environmental assessments, for a licence which will then be approved on a case-by-case basis by parliament.

Marianne Sivertsen Næss, chair of The Standing Committee on Energy and the Environment, which considered the original plan, told the BBC that the Norwegian government was taking a “precautionary approach to mineral activities”.

She said: “We do not currently have the knowledge needed to extract minerals from the seabed in the manner required. The government’s proposal to open an area for activity enables private players to explore and acquire knowledge and data from the areas in question. Opening up areas is not the same as approving extraction of seabed minerals.”

Mr Sognnes, of Loke Minerals, added that the government’s plan would bring in much-needed investment from the private sector for research of deep marine environments.

“Develop[ing] knowledge on the deep ocean is very costly, you need to operate robots and these are very expensive and unfortunately the universities have limited access to these kind of tools,” he said. He estimated that any actual extraction would not begin until the early 2030s.

Campaigners argue that more investment should go into recycling and reusing the existing minerals we have mined on land. The Environmental Justice Foundation estimates in a report that 16,000 tonnes of cobalt per year, about 10% of annual production, could be recovered through improved collection and recycling of mobile phones.

While Norway’s proposal concerns its national waters, negotiations continue on whether licences could be issued for international seas.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) – a UN-affiliated body – will meet this year to try to finalise rules, with a final vote expected in 2025. More than 30 countries are in favour of a ban, but countries such as China are keen to see the ISA press on.