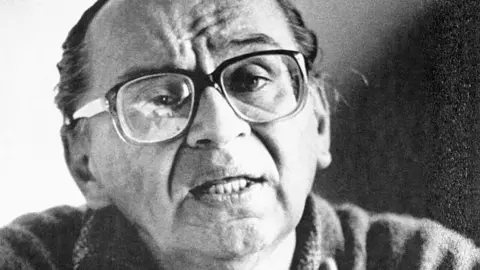

Liberation theology icon and champion of the poor Gutiérrez dies

A Peruvian priest who founded liberation theology, a movement advocating an active role for the Roman Catholic Church in fighting poverty and injustice but reviled by some as Marxist, has died.

Father Gustavo Gutiérrez was 96 when he passed away on Tuesday in his hometown of Lima.

A theologian who later became a Dominican friar, he revolutionised Church teachings with his 1971 book Theology of Liberation.

His progressive theories were embraced by many in his native Latin America but were also met with opposition and even disdain from more conservative voices within the Church.

He drew criticism from no other than Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, who later became Pope Benedict.

The cardinal feared that liberation theology’s “Marxist ideas” would foster rebellion and division, even labelling it as a “fundamental threat to the faith of the Church”.

Relations between the Vatican and Father Gutiérrez thawed somewhat after his fellow Latin American, Jorge Mario Bergoglio, became Pope.

Father Gutiérrez praised Pope Francis for speaking about “a poor Church for the poor” and in 2018, Pope Francis sent Father Gutiérrez a letter for his 90th birthday thanking him “for what you have contributed for the Church and humanity through your theological service and your preferential love for the poor and the discarded of society”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBefore becoming a priest, Gustavo Gutiérrez had studied medicine and literature in Peru, philosophy and psychology in Belgium, and theology in France.

During his time in Europe, he read the works of German philosopher Karl Marx.

His detractors often said his emphasis on helping the poor was Marxist and decried him as a communist.

Liberation theology became particularly controversial when priests who followed a radical strand of liberation theology joined revolutionary movements such as the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, who overthrew the dictatorial government of the Somoza family.

But Father Gutiérrez maintained that his teachings were far from revolutionary but rather squarely rooted in the Bible.

He said that upon his return from Europe to Peru, he had found that the Church was often “answering questions that weren’t being asked”, implying that the Church hierarchy had become too far removed from the troubles of its parishioners, especially in deprived and poor areas.

He argued that the clergy had a lot to learn from the faithful in the poorest parishes who, he said, demonstrated day after day how hope could spring amidst suffering.

In his book The hermeneutic of hope, he recalled how he had fought against a view prevalent among many faithful at the time that “we are born to suffer”.

“No one is born to suffer, but to be happy,” he wrote. “Poverty is a human construction; we have made these conditions.”

Described by his parishioners as a “humble man with a great capacity to make friends”, he combined his work as a theologian and lecturer at top universities with his work as a priest, officiating at weddings and holding retreats.

Félix Grández, a Peruvian sociologist who first met Father Gutiérrez at a spiritual retreat in 1978, said the priest radiated “a happiness which stemmed from doing good, from his dedication to the poor”.

Mr Grández told the BBC that one of the priest’s gifts was to distil theology into clear messages which appealed to the young, something he said he saw Father Gutiérrez do when he officiated at Mr Grández’s own wedding and again at that of his daughter.

“He was well known as a theologian but the way he connected with people was through talking about chess, traditional music, cinema, and his support for Alianza Lima football club.”

Another parishioner who was married by Father Gutiérrez said she felt “immense gratitude for his life and all that he has contributed to the Church”.