Increase investment in public basic education to improve standards

Africa Education Watch in partnership with the Coalition Against Privatisation and Commercialisation of Education, the All-Africa Students Union, the National Union of Ghana Students, with support from OXFAM International, is implementing the Education Spike Campaign aimed at promoting investment in public basic education to improve quality, as commercialisation adversely impacts on access, equity and standards in pre-tertiary education.

Background

Under Article 38 (2) of the 1992 Constitution of the Republic of Ghana, the government has an obligation to provide free quality basic education for all Ghanaian children, irrespective of gender, geography, religion, socio-economic status or one’s disability.

Ghana has over the past decade made gains in expanding access to Basic Education by increasing Primary School enrolment from 3,809,258 in 2010 to 4,511,268 in 2019 and Junior High School (JHS) enrolment from 1,301,940 in 2010 to 1,678,132 in 2019.

Yet, more than 400,000 children, approximately 1 in 4 pre-primary aged children are still not enrolled in kindergarten due to factors, including economic barriers.

We recognise that quality basic education has been skewed in favour of private schools to the detriment of public schools, a situation leading to an inevitable high demand for private education and low demand by the citizenry for public basic education.

This has over the years led to significant inertia by the state in expanding access to public basic education in urban and peri-urban areas, thereby slowing the construction of schools in these areas.

An analysis of the growth of school’s data over the past decade reveals that the number of public schools increased from 36,822 in 2010 to 42,010 in 2020, an increase of about 14 per cent.

Over the same period, private schools which numbered 18,380 in 2010 increased to 39,070 in 2020, an increase of about 112 per cent.

In municipalities like Adentan, a lower middle-class settlement, about 92 per cent of basic schools are private, with only 7.6 per cent offering free Compulsory Universal Basic Education, making it difficult for the urban poor to access education to fulfil their constitutional rights to education. As a result, over 400,000 Ghanaian children still lack education.

In addition, the lack of JHS in over 4,000 Public Primary Schools continues to affect transition and learning outcomes.

In districts like Zabzugu, about 70 per cent of primary schools do not have JHS to continue their education, a major reason why about 36 pupils/students drop out daily from basic schools.

The status-quo is the result of a gradual decline in basic education’s share of the education sector expenditure from 55.7 per cent in 2008 to 39.5 per cent in 2019, limiting investments, especially in infrastructure within the basic education sub-sector.

In 2017, Parliament passed the Earmarked Funds Capping and Realignment Act, 2017 (Act 947) which among others, capped the GETFund at 25 per cent.

The capping of the GETFund has worsened matters, leaving very little for Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) allocation in the education budget to finance infrastructure.

In 2019, only 6.7 per cent of the education sector expenditure went into CAPEX.

Again, in the entire 2019/20 academic year, only 100 primary schools were constructed across over 261 districts, limiting the ability of Ghanaian children to access primary education and exposing them to the economic realities of available private education.

Recommendations

We therefore call on Government to:

1. Increase basic education’s share of the education sector expenditure to 50 per cent.

2. Amend the capping of GETFund to at least 50 per cent and free resources for basic education infrastructure provision.

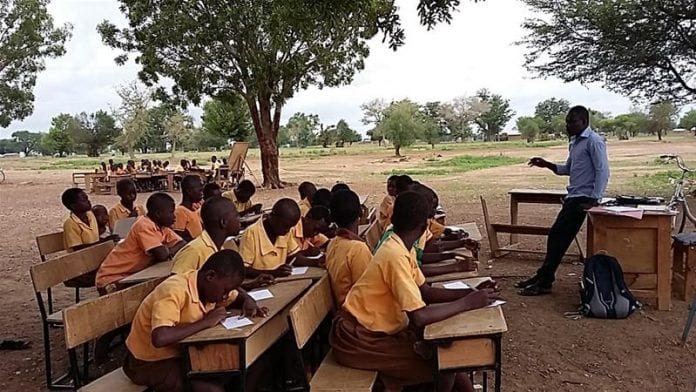

3. Explore other reliable funding to support the VALCO Trust Fund in constructing 5,403 schools under trees within the projected five-year period or less.

4. Explore cost efficient technologies in building schools to improve spending efficiency in the education infrastructure space.

5. Deploy trained teachers to all rural classrooms and strengthen supervision. This should be done by redistributing teachers in over-served schools to under-served ones, and posting new ones to achieve at least, a maximum of 1:35 Class-Pupil Teacher Ratio.

6. Secure funding to construct about 4,000 JHS in all primary schools without JHS within the next five years.

7. Acquire land and construct public schools in urban areas for citizens, especially the urban poor to access Free Quality Basic Education

8. Provide desks, teaching and learning materials in all public basic schools, especially those in rural communities.

9. Ensure timely disbursement of financial resources required to run these schools.

10. Explore the possibility of absorbing collapsed private schools into the public stream to enhance access and re-enrolment of students struggling to re-enter school due to their schools’ collapse because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

It is envisaged that the implementation of the above recommendations would enhance effective teaching and learning at the basic schools and ultimately improve the performance of students.

The writer is Executive Director of Eduwatch