‘I lost 15 relatives to COVID’

Former Namibian football star Marley Ngarizemo has lost 15 relatives including his father, brother, sister-in-law and an aunt since the third wave of Covid hit the southern African nation last month.

Another six currently are in hospital.

“You do not know whether the world is ending,” says the 42-year-old, who played for Namibia at the 2008 Africa Cup of Nations.

“You can compare it to a tsunami, you can compare this to a volcano, you can compare it to genocide. I don’t know. It’s like there is poison in the water, and every drop you take might have it, or might not have it.”

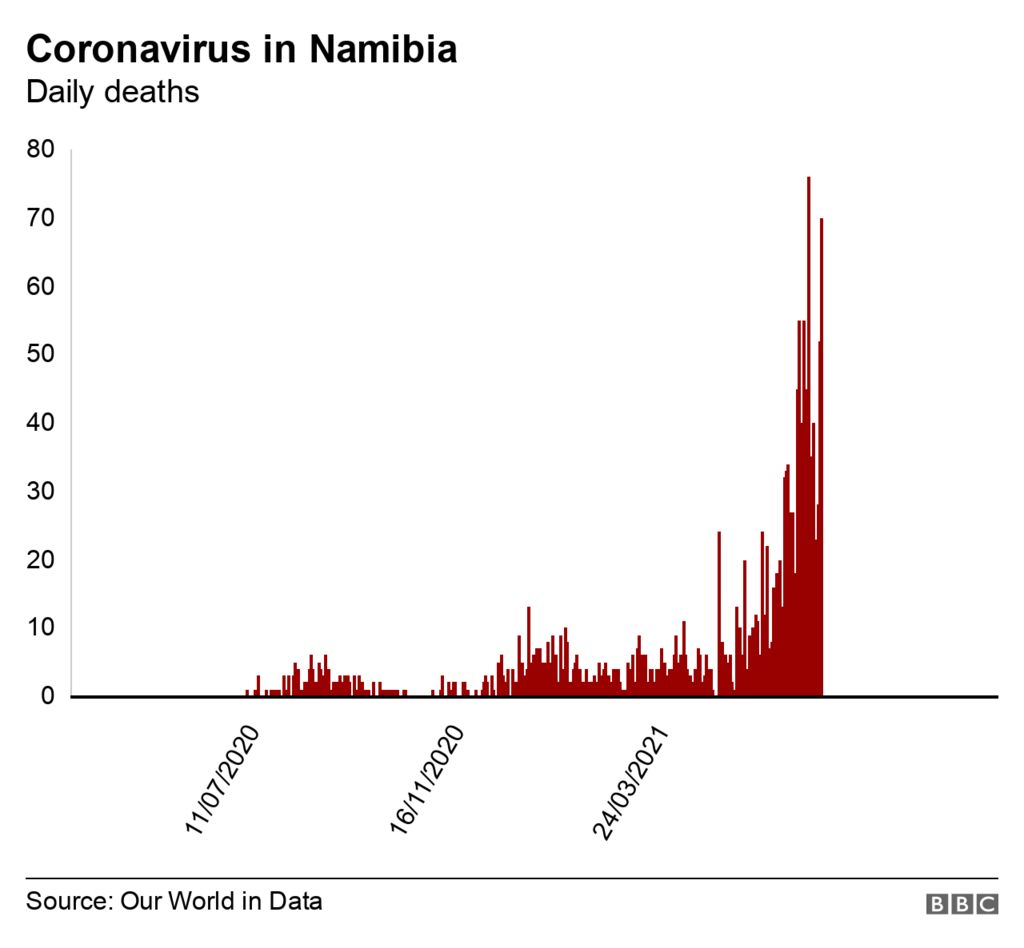

Namibia, which has a population of 2.5 million, currently has the world’s highest death rate, at 22 per million people, according to Our World in Data. Tunisia has the second-worst rate at 13 and Suriname the third at 10.

To help cope with the continuing rise in cases, the government has built makeshift hospitals to accommodate patients. But even with those, health facilities and healthcare workers cannot keep up.

Not only are the number of sick Namibians rising, but so are the number who need to be treated in hospital.

The new isolation centre at the main hospital in the capital, Windhoek, is an unassuming building.

It looks like it was dropped into the middle of the car park.

Oxygen shortage

Before they enter the ward, the nurses have to put on full protective equipment, with multiple layers of masks and gloves, and special boots.

It takes 15 minutes.

The nurses are constantly going through this procedure so that they are able to monitor the oxygen levels of patients, most of whom are sleeping or are in a semi-conscious state.

Donnovan Soresbeb says this wave has been physically and emotionally exhausting for him and his fellow nurses, adding that it was scary how quickly the condition of a patient could deteriorate.

“You lose patients that were okay a few minutes ago. You turn your back, and then they’re gone,” the nurse tells the BBC.

“Some are [staying] so long in hospital, that you kind of give up on them, and it is hard, but you keep hoping for the best.”

Hospitals across Namibia are at capacity and there is not enough oxygen for patients.

Doctors have described having to make decisions “for the greater good”, in which they take sick patients off oxygen to save the supply for a patient who is more likely to survive.

Mr Marley’s father was a victim of the lack of oxygen.

When he took a turn for the worse, doctors immediately put him on oxygen. But once his numbers improved, the oxygen was removed.

Less than 24 hours later, Mr Marley’s father had passed away.

Namibia was unprepared for the third wave, due to a perfect storm of government complacency, misinformation regarding vaccines and a deep case of fatigue with measures to control the spread of the virus.

Social media has been flooded with fake posts criticising the safety and efficacy of the vaccines.

Those who do want to get a vaccine, do not know if and when it will be available to them because of shortages, and the government has been changing its stance on how it should be distributed.

During a sombre address to the nation at the end of June, President Hage Geingob told Namibians that the worst was yet to come.

“Expert projections and simulation tools indicate that the rising incidence curve, during this third wave, is expected to peak around mid-August and may continue well until mid-September 2021,” he grimly stated while announcing a raft of lockdown measures.

“Only you and I can stop the further spread of this virus from ravaging our homes and communities,” he concluded.

Despite this appeal, many Namibians continue to disregard the rules.

Masks hang off one ear and rarely cover peoples’ mouths and noses.

Food markets, clothing stores, and restaurants will chase you down with hand sanitiser when you walk in, but they are not limiting the number of people who can enter.

Large gatherings of young people are still taking place in public spaces, in breach of regulations that supposedly restrict gatherings to 10.

One group of teenagers who regularly meet up in a Windhoek shopping mall said they were worried about passing on the disease to their elders, but they also want to socialise.

There are signs though that some are beginning to take things more seriously.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESFor example, initially people in the country’s Herero community, which makes up about 7% of the population, appeared to ignore warnings and continued with big traditional gatherings.

Then as some died, the funerals themselves became super-spreader events. But the recent passing of a paramount chief, Vekuii Rukoro, changed attitudes.

There is fear everywhere, says Herero elder Josua Musuuo.

“The whole nation is dying, this corona is finishing us. All the elderly are dying.

“So, everyone at the village homesteads and all these people sitting here are all in fear, fear of death, they are all waiting to die.”

As for Mr Ngarizemo, he believes that a lot of the deaths in his family could have been avoided had the government introduced tighter restrictions earlier, and communities had taken more personal responsibility.

“Imagine people have survived HIV and now people are just dying by this disease – left, right and centre – and no-one can manage it. It’s really tough, it is frightening.”