How Ghana’s economy became a cautionary tale for Africa

In the centre of Accra lies a deserted construction site that is a symbol both of Ghana’s ambitions and its afflictions. Here is where the National Cathedral of Ghana is set to be built — the passion project of the country’s president, envisioned as a national landmark and a centre of religion to rival Westminster Abbey and Abu Dhabi’s Grand Mosque.

Sitting on a tree-lined street just off the major thoroughfare of Independence Avenue, the multimillion-dollar development was proposed in 2017, the year Ghana celebrated 60 years free from British rule. Once completed, it will be a 5,000-seat place of worship to accommodate formal events such as presidential inaugurations and state funerals. But six years on, President Nana Akufo-Addo’s legacy-defining grand vision has stalled — while the economy he presides over is in tatters and citizens struggle under the weight of crushing inflation. The building project is a cautionary tale not only for Ghana but for many countries in Africa that overspent on infrastructure and now face the bill.

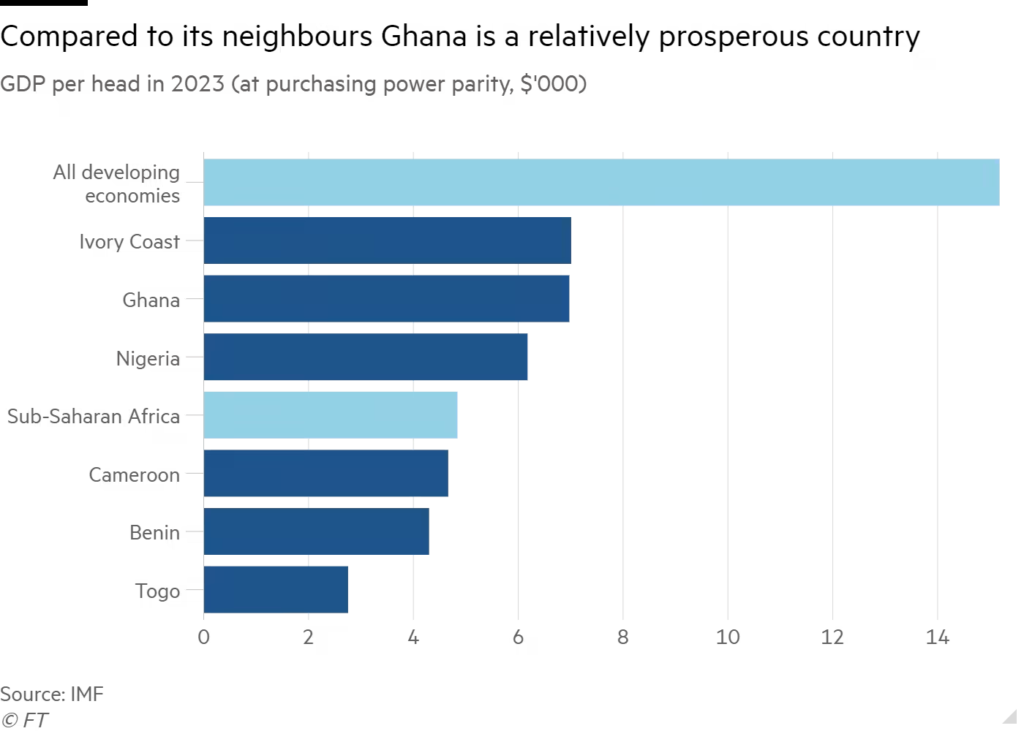

Ghana has long been considered a success story and a model for African development. It is a major producer of gold and cocoa and has one of the region’s highest gross domestic product per head. A robust democracy since the early 1990s, it has a relatively well-run government that provides decent levels of public service, including free education. The global African diaspora seeking a connection with their ancestral land regard it as a must-visit destination.

The current government, in particular, burnished an image of fiscal responsibility and technocratic nous, something that enabled it to tap commercial debt markets at decent rates of interest. That reputation now lies in ruins. Ghana had just agreed a $3bn bailout from the IMF when it defaulted on its debts last December, a fate that could soon befall 19 other countries on the continent, according to the fund. Like Ghana, many have borrowed heavily to fund projects — whether railways, roads, ports or airports — that have failed to generate enough income to pay back debts, particularly in an environment of high interest rates and a strong dollar. To further complicate matters, the threat of insecurity is now on Ghana’s doorstep due to unrest in Burkina Faso, its neighbour to the north, the new epicentre of the jihadist upheaval in the Sahel, the semi-arid strip south of the Sahara.

Yet despite this uncertain outlook, the president remains committed to building a cathedral to serve the country’s 33mn population, 71 per cent of whom are Christians. “The National Cathedral is an act of thanksgiving to the Almighty for his blessings, favour, grace and mercies on our nation,” Akufo-Addo said in January after visiting the site and pledging 100,000 cedis ($8,500) of his own money towards the build.

Many in Ghana are questioning his priorities. About 87 per cent of Ghanaians think their country is heading in the wrong direction, according to data from the Accra-based polling company Afrobarometer. They blame the government and protests have broken out in the past year over the high cost of living.

But instead of being an emblem of unity, for some in Ghana it has become representative of all that has gone wrong here in the past few years — a mothballed site nicknamed, derisively, the “world’s most expensive crater”.

Pain of inflation In Accra’s sprawling Makola market, shopper Tracy Aloko has more immediate concerns than national monuments as she looks wistfully at the bag of tomatoes she has just bought. The same quantity cost about 20 cedis in January, she says. Now, shaking her head, she complains that the same bag costs 50 cedis. And this is a good deal — another vendor just tried to sell her the same amount for 60 cedis. “It’s like hell,” Aloko says, rattling off household items whose prices had skyrocketed in recent months.

Not only are tomatoes, the building blocks of Ghanaian soups and stews, more expensive, but so is gari, the granulated cassava flour that is a food staple across West Africa. She used to buy food in bulk, she says, but has had to cut back due to the “increase in everything”. Ama Mary, the market woman who sold the tomatoes to Aloko, says the cost of the produce has partly shot up due to the Islamist crisis in Burkina, from where Ghana imports a sizeable amount of its tomatoes annually. Ordinary people such as Aloko and Mary are on the frontline of Ghana’s economic crisis, and struggling to adapt to record levels of inflation. Although it has dipped from the two-decade high of 54 per cent in December, inflation remains at 41.2 per cent.

“Life is hard for everybody in Ghana. Everybody is feeling the pinch,” says John Asafu-Adjaye, a senior fellow at the Accra-based African Center for Economic Transformation (ACET) think-tank. “But the ones feeling it the most are those in the low socio-economic groups.” The daily minimum wage was increased by almost 10 per cent to ¢14.88 at the beginning of the year but it is only a tiny reprieve in the face of astronomical price rises. The government says Ghana’s economic misfortune has been caused by the dual external shocks of Covid-19, which ground the economy to a halt, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which sent global food and energy prices soaring.

These were the “malevolent forces” that Akufo-Addo said were hurting his country. Ernest Addison, governor of the Bank of Ghana, the country’s central bank, says the decision of the three big rating agencies to downgrade Ghana to junk status made the economic situation “more complicated” in 2022 as prices climbed steadily. “All the external forces were against us, with Russia-Ukraine, the cost of imported food going up and on the exchange rate we had no access to foreign capital,” Addison says. But analysts say this account only tells half the story.

James Dzansi, chief Ghana economist at the International Growth Centre, an Oxford university and London School of Economics-backed global think-tank, argues Ghana was “walking on thin ice but not sinking” before the pandemic hit. The government borrowed heavily to insulate the economy from the effects of the pandemic and may have avoided a recession as a result. But the country’s debt as a percentage of GDP went from 62.7 per cent in 2020 to more than 100 per cent last year, according to finance minister Ken Ofori-Atta. Debt servicing now takes up about 70 per cent of government revenue. Despite this growing debt load, the ruling New Patriotic Party resorted to a habit in 2020 that Dzansi says bedevils politics in Ghana: overspending in an election year.

The administration stopped charging for mains water and brought in cheaper tariffs on electricity. Analysts say the policy could have been most effective if it targeted those most in need of assistance in a difficult year; instead, it was widely available to everyone, including city-dwelling urbanites who did not require support. “The government saw an opportunity in leveraging the Covid pandemic to engage in reckless expenditure in view of the 2020 election,” Dzansi says.

“You warm the temperature and the thin ice broke.” Perils of cheap money Much of the Ghanaian government’s spending took place in a world of low-interest rates. Ghana gorged on cheap money, raising almost $17bn in eurobonds that the Ministry of Finance frequently said were oversubscribed for nine straight years. But as central banks began raising rates to control inflation — the Bank of Ghana has raised rates by 1,250 basis points since March 2022 — Ghana found itself shut out of international debt markets as concerns grew over its ability to repay what it owed.

The government has since been forced to rely heavily on a domestic capital market, where interest rates are as high as 40 per cent, and central bank financing of 37.9bn cedis ($3.2bn) in 2022. Some of the money being injected into the economy by the central bank may have helped to fuel inflation, says Henry Telli, an economist at the International Growth Centre. Telli says Ghana’s government should have “consolidated” in 2021 by applying “very strong brakes on government spending” the year after the election and should have asked the IMF for help sooner than it did. “Politically, the IMF may not be popular but it is an economic tool,” Telli adds. “It’s available to use when you need a different strategy.”

Ghana did eventually seek relief from the IMF in 2022 as it became apparent that its economy needed outside assistance. Months before, finance minister Ofori-Atta had insisted that no such help was required. By July, after criticism from the opposition and protests in the capital, Ofori-Atta’s position had softened and Ghana began talks with the Washington-based lender for its 17th programme since independence.

“We have our own issues with the IMF but we saw that the country needed external help,” says Mensah Thompson of Asepa, an anti-corruption group that helped organise protests calling on the Ghanaian government to seek aid. “It felt like the people in charge could no longer manage things.” Ghana speedily reached a staff-level agreement with the IMF for a $3bn loan in December, pending approval from the fund’s board if Ghana meets some conditions it has set out. First, Ghana has had to restructure its domestic debt, the first time such a request has been made.

Now, it has to restructure its external debt of about $34bn, most of which it stopped paying in December. Ghana’s bilateral creditors have now formed a committee led by France and China to begin debt restructuring talks, the Paris Club of bilateral creditors has said, clearing the way for the IMF’s board to approve the country’s rescue package. Additionally, Ghana has to stop central bank financing to plug the government’s revenue shortfalls. Addison, the central bank governor, told the Financial Times this month a “zero financing” agreement had been signed with the finance ministry. The government must also increase revenue generation. To achieve this, it introduced new company and income taxes, higher excise duties on goods including tobacco products and alcoholic drinks, and raised VAT by 2.5 points to 15 per cent. Cleaning house The new taxes are already proving controversial. Joseph Obeng, president of the Ghana Union of Traders Association, a trade body, calls them “obnoxious”, adding that they will further increase the cost of doing business. He asks why the government is targeting the few who pay formal taxes and not widening the tax net to bring in more people in the informal sector, which is estimated to make up at least 80 per cent of the economy. At around 13.4 per cent, Ghana’s tax-to-GDP ratio is below the African average of 16 per cent and the government’s own target of 20 per cent by this year. The IMF deal, when approved, could help restore investor confidence in Ghana and slow currency fluctuations that have raised the cost of imports, says Asafu-Adjaye, of the ACET think-tank. But he cautions that it could take time before ordinary citizens feel its impact on the cost of living. Analysts say they hope this economic crisis and the impending IMF programme will spur radical reforms in Ghana. There is a need to plug leakages that deny the government crucial revenues. A report by the auditor-general Johnson Akuamoah Asiedu says Ghana missed out on almost $3bn in revenues in 2021 due to what he described as “irregularities [representing] trade debtors, staff debtors and outstanding loans and cash locked up in non-performing investments”.

But most importantly, there is a consensus among experts that the size of Ghana’s government must shrink. At the outset of Akufo-Addo’s presidency in 2017, he defended his decision to appoint 110 ministers as a “necessary investment to make for the rapid transformation of this country”. At present, there are about 90 ministers, some of whom have two or three deputies. “It’s jobs for the boys,” says Asafu-Adjaye, pointing out that there are many ministries with significant crossover. Ghana has separate ministries for transport, railways development, roads and highways, and aviation, for example. The ministries of information and communications are separate entities.

Please use the sharing tools found via the share button at the top or side of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.comT&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email licensing@ft.com to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found here.

https://www.ft.com/content/bd67731c-cea0-4045-96d4-5fff001f1fd2

Beyond the size of government, corruption is a growing concern. The country was rocked last month when a 2021 report was leaked to the press alleging that government officials have frustrated the fight against illegal gold mining. The government denies the allegations but opposition MPs are calling for a bipartisan investigation.

Kweku Bamford, a young shopkeeper, says he has no faith that the $3bn from the IMF will be judiciously spent given what he says is the rampant corruption in the public sector, pointing to the auditor-general’s report that showed some of the funds mobilised for Covid support were mismanaged. “Ghana’s culture has changed,” he says. “Ghana is a corrupt country right now.”

This perception is reflected in how some Ghanaians see the costly, delayed cathedral — although not everyone has lost faith in it. Solomon Ntiamoah, a taxi driver on his way to attend an evening sermon at the capital’s Black Star Square, is “praying for the project to go on”.

Opoku-Mensah, the project director, still expects it to be completed by the end of next year. But unless Ghana can turn its economy around, Ntiamoah’s prayers are likely to go unanswered.