How elections impact the monies in your pocket

Every entrepreneur who depends on loans to operate is super edgy in election years.

So are investors and ordinary Ghanaians who are faced with a high-interest rate in almost all election years in the Fourth Republic.

For business people, this relationship is important to understand because it impacts their revenue before and after elections.

As the Bank of Ghana (BoG) announces its last Monetary Policy Rate (MPR), the primary determinant of interest rates, theghanareport.com examines the correlation.

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, the BoG cut the MPR from 16.0% to 14.5% in March 2020.

The apex bank has since gone ahead to hold it for four consecutive times, ending the year at the same rate.

The government has indicated rolling out GHC 10 billion cedis ($1.71 billion) of bonds to help finance the 2021 budget.

If the apex bank had cut the last MPR, it would have resulted in a lower interest rate, a disincentive for investors to subscribe for domestic and international bonds issued by government.

It means the government’s sources of funds to finance the 2021 budget would be adversely affected.

Governor of the Bank of Ghana, Dr Ernest Addison, said, “That could create serious complications for the economy.”

On the safer side, the apex bank chose to maintain the MPR once more.

Inflation, which is the rate at which prices of goods and services go up, is currently at 10.1% while Gross International Reserves USD 8.6 billion with an import cover of 4.1 months at the end of October 2020.

So, before we proceed, let’s understand MPR.

What is Monetary Policy Rate (MPR)?

MPR is the rate at which the Bank of Ghana lends money to commercial banks.

Consequently, this affects interest rates in the country and inflation.

The BoG had its operational independence after the Bank of Ghana Act, 2002 (Act 612).

Subsequently, the BoG added inflation management as one of its main objectives.

Through price stabilisation and other mechanisms, it can control inflation.

The apex bank achieves its inflation targets by implementing the MPR, which is determined by the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the central bank.

If inflation is going up, then it means there is excess money in the system than required for the purchase of goods and services.

An increase in the MPR will increase interest rates, making investment attractive for investors.

Individuals will be more encouraged to save and invest their monies at higher interest rates, and this would mop up excess money (liquidity) from the system.

Commercial banks will normally go to the central bank to borrow at a higher interest rate as a last resort.

If the banks decline to go for loans from the apex bank, there would be less loans for individuals and businesses.

So, one way of also mopping up excess liquidity is not to give out loans.

When the inflation is down, the BoG will loosen the MPR also to fulfil the mandate of stimulating growth.

More commercial banks are likely to borrow and also forward loans to businesses and the public.

Trend and findings

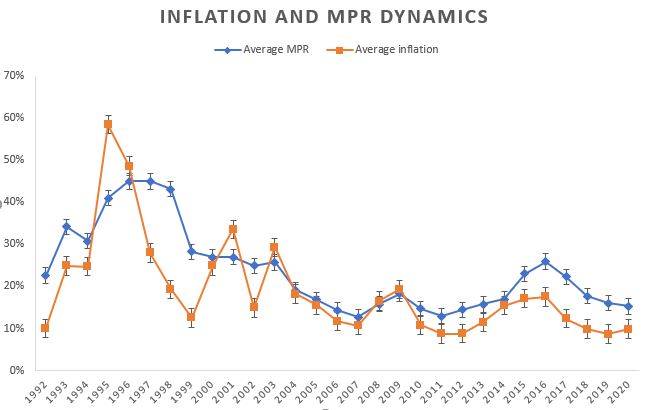

An analysis of historical data showed high inflation in elections years forcing a surge in MPR to keep it in check.

Out of six elections from 1996 to 2016, four have recorded an increase in MPR in election years.

1996, 2008, 2012, and 2016 witnessed an increase in MPR to control inflation.

“Usually, when we are approaching election we tend to overspend, and that stokes inflation, and because we are an inflation-targeting central bank, they would increase MPR anytime there is a risk to the inflation outlook,” Economic Analyst at Databank Group, Mr Courage Kwesi Boti, explained in an interview with the ghanareport.com.

In the first four years, an incumbent government is confident that Ghanaians would give them a second term, so the over expenditure is minimized, but normally “after eight years, that agitation to stay in power drives them to spend more,” he added.

The highest policy rate recorded in the Fourth Republic was 48.6% in 1996.

This was aimed at correcting the high inflation of 58.5% in 1995 and 48.6% in 1996.

Mahama vs Akufo-Addo: Who did better with MPR?

Even though political administrations normally appoint the BoG Governors, they have largely operated independently.

However, the governments have claimed credit when the BoG policies yield fruits.

“Inflation was already on a decline” when the Akufo-Addo-led NPP took office in 2016.

This was due to the IMF programme signed by Mahama’s NDC government, which necessitated prudent economic management to fulfil the conditionalities.

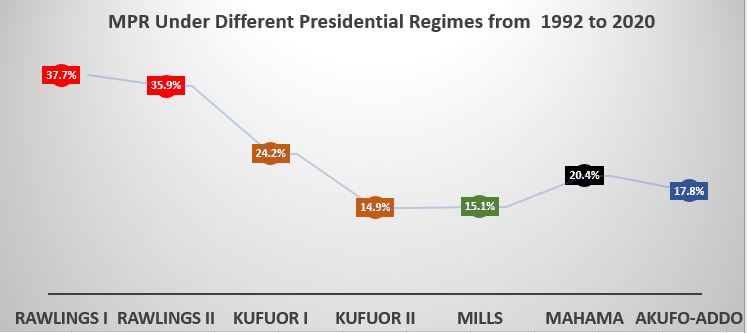

However, the current government is credited for slashing the MPR significantly from the previous government’s average of 24.0% to 17.8%.

2016 alone had an MPR as high as 25.9%.

Rebasing (reconstituting) the inflation basket in August 2019 considerably led to a decline into a single digit.

The Akufo-Addo-government kept reducing the MPR because inflation was down and shifted to stimulating growth, leading to a decline of interest rate from the banks.

As at October 2020, the Average Lending Rate was 21.26% under the current government.

At the same period in October 2016, Average Lending Rate was 32.1% under the previous government.

The MPR accounts for about 40% of the basket of indices that are used to calculate the Ghana Reference Rate (GRR), a benchmark rate that banks now use to set their lending rates.

It is, however, important to emphasise that due to huge Non-Performing Loans (NPLs) on the books of banks, reduction in interest rates tend to have a slow response to a cut in MPR.

With MPR determining how companies expand or contract, the output of the country is affected.

Mr Mahama’s tenure was marked by power crises that lasted more than a year.

Similarly, Akufo-Addo’s tenure has been rocked by the COVID-pandemic that has wiped out a chunk of economic gains, and there appears to be no end in sight.

Job losses & the collapse of many informal, micro and small businesses – many of which are owned by #women – have pushed many out of the financial system – @thebankofghana Governor Ernest Addison at the #afiGender #COVVID19Response webinar.#financialinclusion #SDGs @Sida pic.twitter.com/fAIDXcGqXu

— AFI (@NewsAFI) September 14, 2020

Figures from the World Bank showed that Ghana’s GDP growth rate in 2015 was 2.1% which climbed to 3.5% in 2016.

In 2019, it had surged to 6.5% but declined sharply in early 2020 due to the pandemic.

In October, the World Bank projected that Ghana would end 2020 with a growth rate of 1.7%.

Besides GDP, the BoG also uses an aggregate of indexes, grouped and called the Composite Index of Economic Activity (CIEA) to guide the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee.

According to the Monetary Policy Analysis Division of the BoG, the CIEA tracks the GDP very closely and is taken by the BoG as an excellent indicator of business confidence.

In the latest Summary of Economic and Financial Data for November 2020, the Real CIEA had defied the pandemic and risen to 10.5% in September.

Within the same period of September 2016 under the previous government, the CIEA was 3.4%.

Commenting on the growth, Mr Boti noted, “The more accommodative policy regime that coincided with the Akufo-Addo administration has actually stimulated the kind of growth we are seeing supported with government’s programmes, and the cautious stand also meant that they had contained inflation that is why we are not seeing a spike in inflation like previous times”.

He added: “Monetary regime now has supported the growth and sustained disinflation in the system”.

MPR under Rawlings, Kufuor and Mills

Former President Jerry John Rawlings’ era witnessed the highest policy rates as high as 37.7% whiles the lowest was under former President John Agyekum Kufuor (14.9%).

Mr Boti attributes the lowest monetary policy achieved to the Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) programme opted by the Kufuor government in 2001 from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The decision point to end the programme was in February 2002.

After offering monetary aid and cancelling a chunk of Ghana’s debt, the Bretton Wood institution attached conditionalities to ensure efficient management of the country’s economy.

The macroeconomic objectives of the programme dictated that government should have achieved “by 2004 a single-digit inflation rate (5 per cent), an acceleration of the real rate of economic growth (to at least 5 per cent), and the restoration of a prudent level of official foreign reserves (equivalent to about three months of imports)”.

The result was a drastic cut in inflation from 33.6% in 2001 to 10.7% by 2007 before exiting office.

“The government was at that time very disciplined, and that achieved the lower inflation we had,” Mr Boti intimated.

However, the latter part of Kufuor’s second term saw a bit of indiscipline resulting in a spike in inflation.

Election 2020 and 2021 forecast

In less than a month, Ghana will be heading to the polls.

There are fears of budget overruns and expenditure that could affect inflation.

COVID-19 concerns have also led parliament to suspend the Fiscal Responsibility Act, which permits the Finance Minister to limit expenditure to 5% of GDP.

The World Bank is expecting the fiscal deficit (excluding the energy sector and financial sector costs) to widen to 11.4% of GDP in 2020.

The apex bank is projecting single-digit inflation by the second quarter in 2021 and “if there would be any cuts at all, probably late in the third quarter” of 2021, Mr Boti noted.

If this occurs, the economist predicts a slash in MPR which “could come down to 11 or 12%”.

So in summary, the country has generally seen better economic stability and growth under the ruling government than any other…. These are based on facts and hard data but not all arguments are logical in politics so…

Lovely piece David. Very educative and informative.

More of such articles please.

This is very informative. And it is straight to the point for anyone who wants to understand. Thanks for this great piece.