Ghana’s central bank is caught between cutting interest rates to boost the economy and running the risk of weakening the currency, which could drive up inflation and spook investors ahead of December’s elections.

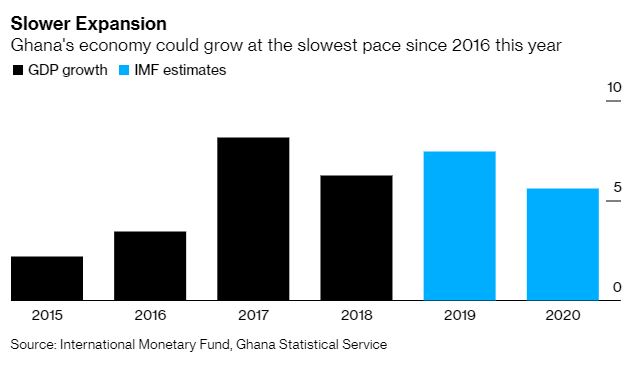

One the one hand, inflation ended the year slightly below the government’s projection and economic growth slowed in the third quarter, giving room for an interest rate cut. However, a repeat of the government missing its fiscal targets in previous elections years could fuel price growth and weigh on the currency, causing debt costs to soar.

Economists are divided on the central bank’s path forward. Of the eight economists in a Bloomberg survey, five forecast Governor Ernest Addison will keep the key rate at 16% on Friday, and three predict a 50 basis-point cut.

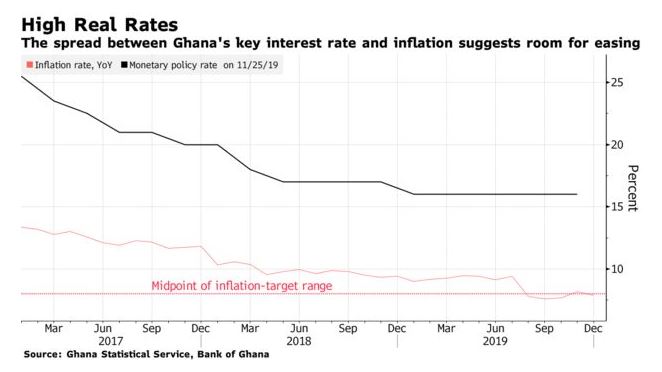

President Nana Akufo-Addo is seeking lower lending rates and told a gathering of bankers in 2018 that their refusal to pass on monetary easing was hindering growth. While the policy rate has already reduced by 950 basis points since Akufo-Addo came to power in January 2017, the upcoming election, in which he will seek a second term, may add more pressure for further cuts.

“The president wants to see interest rates down, but I believe he’s being well advised by the governor,” Peter Quartey, a director at the Accra-based Institute of Statistical, Social and Economic Research, said by phone. “Supposing a rate cut would enhance the chances of him being re-elected, I don’t think the monetary policy committee will bow to such external pressure.”

Ghana is targeting a budget deficit of 4.7% of gross domestic product this year, from 4.5% recorded in 2019, but it may prove difficult because growth is forecast to slow, revenue collection has trailed targets since 2016 and Akufo-Addo wants to deliver on projects promised to voters. This could fuel inflation to close to 10% by the end of the year, Yvonne Mhango, a sub-Saharan Africa economist at Renaissance Capital, said by phone from Johannesburg.

“Due to the elections, the contingent fiscal overruns mean the risks to the currency from cutting are even higher than last year,” she said.

The cedi dropped almost 8% against the dollar in the month after the MPC unexpectedly cut by 100 basis point last January. Foreign investors’ share of outstanding government debt maturing in at least two years fell to 38% by November, down from 60% in 2017.

A possible increase in bailouts to failed banks by 22% to 20 billion cedis ($3.6 billion), plans to raise capital spending by more than half and liabilities falling due in the energy sector are sources of risk for the budget in 2020.

“In this context, monetary policy will have to adopt a more prudent stance to help contain upside inflation risks,” Leslie Dwight Mensah, an economist at the Accra-based Institute for Fiscal Studies, said by phone. “If they were to succumb to any political pressure they know that the market will punish them.”

Credit Growth

Still, the uptake of credit is slow. The rate of growth in private credit extension has exceeded 20% in only two of the 36 months since the easing started. The spread between the key interest rate and inflation is close to an 18-month high and the cedi has made some gains since reaching a record low against the dollar in December.

“The recent currency strength gives the central bank a little bit of room to be able to cut,” according to Neville Mandimika, an economist at FirstRand Ltd.’s Johannesburg-based Rand Merchant Bank unit. “The current GDP growth is below potential rate. The central bank, given their mandate, should be able to support growth by lowering the rate and boosting credit appetite.”

Despite the cedi’s gains, it’s still 11% weaker than it was a year ago. While scope exists for the MPC to ease policy later this year, it may take a more cautious approach on Friday to encourage further progress on the currency, Societe Generale SA’s London-based strategist Phoenix Kalen said in an emailed note.