Fringe acts pay price for thrill of performing in Edinburgh

The Fringe began on the edge of the first Edinburgh International Festival in 1947.

Eight companies, who felt the new festival underserved theatre, simply turned up and performed anyway.

Today the Edinburgh Festival Fringe has outgrown the international festival, offering 3,841 shows in 262 venues.

Seven hundred reviewers will attempt to separate the wheat from the chaff, while 1,300 arts industry professionals will scour the city for shows to take on tour, or make into television.

Baby Reindeer, Fleabag and Nanette all began life at the Fringe.

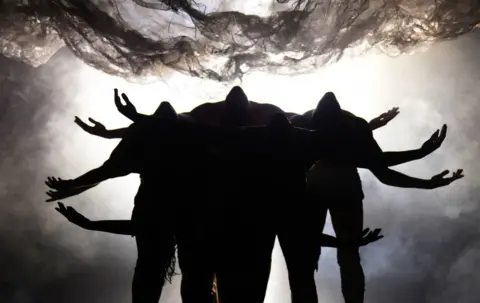

Acrobatic act A Simple Space, Gravity & Other Myths return to Edinburgh

With an estimated 52,000 performances between now and the end of August, the Fringe retains its title as the world’s largest arts festival, but those involved say it’s an increasingly fragile environment.

Barely recovered from the pandemic, performers face spiralling costs.

Accommodation in particular is said to have tripled since 2019, with a squeeze on many affordable options due to the change to short term let agreements.

“I think it’s been the hardest four years I’ve known,” says William Burdett Coutts of Assembly, who is marking his 45th year in Edinburgh.

“We create a great jamboree event which the public love. But underneath it there’s a lot of swan’s legs paddling very fast. “

But the thrill of performing at the world’s largest arts festival seems to outweigh any concerns about cost.

At Dance Base in the Grassmarket, 10-year-old Alfie is making his Fringe debut in ‘The Show for Young Men’, and 81-year-old Christine Thynne will make her solo debut in ‘These Mechanisms’.

“It’s quite terrifying but also exciting,” says Christine.

“I think I’ve been blessed with good genes when it comes to joints. I don’t have any arthritis and it allows me to try out new things with my show.”

“I feel really, really nervous, “ says Alfie.

“But this is not a practice. This is the Fringe.”

Alfie says the best thing about being part of the Fringe is the friends he has made.

And Christine has some advice for his debut: “Just enjoy it, and breathe as you go on.

“This is the start of your career. You will always remember this first time.”

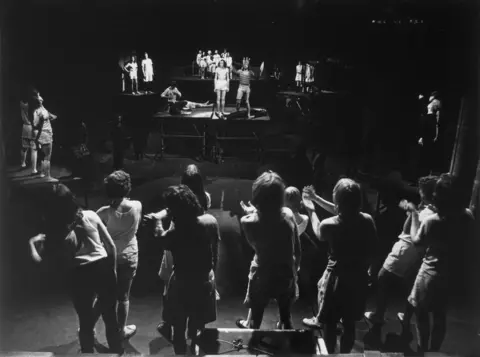

Strathclyde Theatre Group can vouch for that. Fifty years ago this summer they presented their show The Golden City at the Fringe.

“It took more than a year to create, an epic extravaganza,” says Donald Fraser, who was a lecturer at Strathclyde University.

“We found the story from 16th Century Munster and staged it in Glasgow Cathedral and then at the Fringe. “

The promenade production, with audience participation, was ambitious and groundbreaking.

It won them a Fringe First award but it also cost twice the anticipated bill of £3,000.

“Sums nowadays wouldn’t worry anyone,” says Trevor Griffiths, a retired professor of drama who was front of house for the production.

“But although the university was happy to see the English department making a name for itself, they weren’t happy about the additional costs.

“After the show, I was called in and asked to organise ways of fundraising to recoup the money.”

In 1974, the first year the Fringe outsold the international festival, tickets for the Golden City cost 60p each.

The show is celebrated in a new exhibition of photographs and memorabilia at Fringe Venue 91 – St Mary’s Cathedral in Palmerston Place.

A number of the original cast and crew gathered for the opening. Among them, Anita Gailey, then Miller.

“I was a townsperson but because the show had so many styles, I played lots of different roles.

“It began with a carnival, so we were limbo dancers and then there was a panto scene where I was Alice in Wonderland. I was always a shy person but that helped me.”

Anita became an actor but later retrained as a psychologist.

“My life has been very rich and I think the Golden City probably played a big part in that.”

“I can understand the attraction of the fringe,” says Donald, “although I preferred it when it wasn’t such a scrum. People stayed in other people’s flats, or drove from Glasgow.”

But Trevor Griffiths says it’s a reminder of what’s possible at the Fringe.

“We were just a bunch of 20-year-olds doing the best we could and it really changed many people’s lives.”

“It showed people they could really do something ambitious

“We all felt challenged in a good way. Many people went on to do great things afterwards, not just in theatre, but in all walks of life.”