Facebook Sees WhatsApp As Its Future, Antitrust Suit or Not

On the final day of November, Facebook Inc. announced it had bought a customer service software startup most people had never heard of, in a deal valuing the company at more than $1 billion.

Although it was the third-largest acquisition in Facebook’s history, slightly more than it paid for Instagram in 2012, the deal drew very little notice. In Washington, where regulators are actively pursuing antitrust lawsuits against Facebook and politicians condemn almost every move the company makes, the purchase of Kustomer Inc. was met with crickets.

But if the deal’s significance isn’t clear now, it could be soon. Acquiring Kustomer is the latest in a series of expensive bets related to Facebook’s $19 billion purchase of WhatsApp in 2014. Earlier this year it invested in Jio Platforms, an Indian internet giant that WhatsApp plans to partner with on commerce. While not an acquisition, the $5.7 billion Jio investment was Facebook’s second-largest financial deal ever. Taken together, the moves add up to an investment in private messaging of about $26 billion.

Facebook has been under the microscope for its impact on U.S. politics and its outsize role in the economy. On Dec. 9, state and federal officials filed sweeping antitrust lawsuits against Facebook, saying it has acquired smaller companies to head off competitive threats, and seeking to unwind some of those purchases.

One of the deals mentioned was Facebook’s purchase of WhatsApp—the world’s largest messaging service, with more than 2 billion monthly users. While the app makes relatively little money now, Facebook sees private messaging as the foundation for its next big business, presenting it with one of its biggest challenges, even if the antitrust scrutiny doesn’t complicate matters.

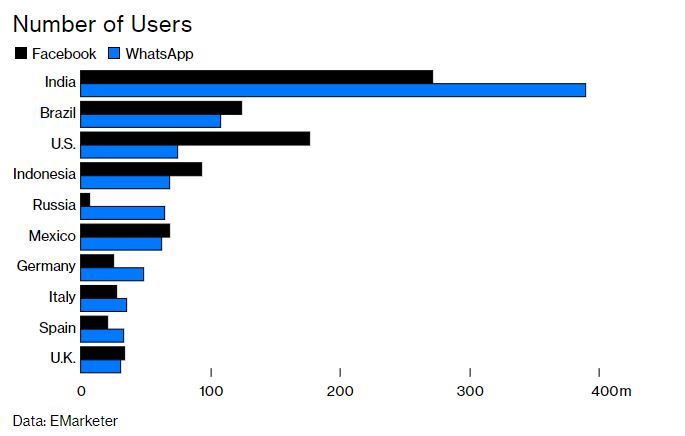

WhatsApp doesn’t loom especially large in Facebook’s home market, but it’s huge almost everywhere else—especially in India, where it says it has more than 400 million unique users a month.

Chief Executive Officer Mark Zuckerberg sees potential to transform that user base into a profit center by enticing retailers to sell goods and services inside WhatsApp, or use the app to handle customer service issues that might otherwise require an email or phone call.

For Facebook, a company that makes 99% of its revenue from advertising, WhatsApp presents a chance to diversify its business and protect itself from erosion in enthusiasm for its core social networking apps.

Eventually, Facebook believes, it can control the entire exchange between a brand and its customer, starting with an ad on Facebook or Instagram and leading to an interaction or product sale on WhatsApp or Messenger. “Instagram and Facebook are the storefront,” says WhatsApp Chief Operating Officer Matt Idema. “WhatsApp is the cash register.”

Early in 2019, Zuckerberg wrote a 3,200-word blog post outlining a strategy to make all of Facebook’s other products look more like WhatsApp. “I believe the future of communication will increasingly shift to private, encrypted services,” he wrote at the time. “This is the future I hope we will help bring about.”

The two companies were an odd couple from the start. WhatsApp’s founders, Jan Koum and Brian Acton, launched it in 2009 as a free alternative to SMS text messages. Koum, who’d grown up in Soviet-controlled Ukraine before attending San Jose State University, was uniquely sensitive to concerns about privacy.

“The walls had ears,” he once said of his childhood. By the time of the Facebook acquisition, WhatsApp was working on end-to-end encryption, a technology that makes it impossible for the company to read user messages, even if a judge asks it to.

WhatsApp’s mantra before the acquisition was “No Ads! No Games! No Gimmicks!” Facebook had built an advertising empire based on persuading users to make as much of their lives public as possible.

The company not only had access to their posts and conversations, it also relied on that data to train its algorithms and determine what things people should see—and to allow advertisers to target their messages to specific audiences, a business model at the center of much of the political controversy surrounding Facebook.

Koum was obsessed with reliability and would later say he’d deliberately tried to slow WhatsApp’s growth to avoid technical challenges. The approach was the exact opposite of the one favored by his new boss, who’d given Facebook the unofficial motto “Move Fast and Break Things.”

When Koum sold the company to Facebook, WhatsApp had 450 million users and just 55 employees. Its only source of revenue was a $1 annual subscription fee. As part of the deal, Koum got a seat on Facebook’s board and a pledge from Zuckerberg that the company could continue to operate independently, free from ads.

Zuckerberg’s promise stuck, at least for the first few years. When WhatsApp employees moved to the main Facebook campus, a few years after the deal closed, they were able to keep the bigger desks they’d enjoyed when they were independent.

The parent company even installed larger doors on the restroom stalls in the WhatsApp area, giving them a little additional privacy. It became a symbol of the clashing cultures: Even WhatsApp’s bathrooms had to be end-to-end encrypted, some Facebook employees joked.

But by mid-2016, Zuckerberg wanted the app to make money. Koum and Acton suggested charging businesses a small fee to send messages to their customers on the app, but top Facebook executives said that business wouldn’t be big enough and pushed WhatsApp to sell advertising instead, according to people familiar with the company.

Facebook also ordered WhatsApp to change its terms of service to allow Facebook to use people’s phone numbers to link their accounts on the two services. The stated purpose was to offer Facebook users better friend suggestions, but the move also opened up the possibility of using a person’s Facebook details to show them targeted ads on WhatsApp.

Koum and Acton fought back. At one point, when Zuckerberg asked them to replicate Snapchat’s Stories feature inside WhatsApp, they used the assignment as an excuse to delay working on other ideas to generate revenue, former employees say. Not long after, they resigned.

Acton, who left in 2017, invested $50 million to help start the Signal Foundation, a nonprofit that runs a competing encrypted messaging app. He also posted a message on Twitter that left little doubt about his feelings. “It is time,” he wrote, and then added a hashtag: “#deleteFacebook.”

Ironically, Facebook eventually came around to a plan resembling Koum and Acton’s. WhatsApp is now run by Will Cathcart, a top Zuckerberg product lieutenant, who says his focus is on commerce and business services rather than ads. Facebook’s other messaging app, Messenger, has sold ads since 2017, but it’s never grown into a big business.

Facebook has said it may eventually sell ads in WhatsApp as well. But the only way WhatsApp makes money today is by charging businesses to send messages to customers in lieu of email or phone calls. “You gotta kinda pick, and pick the things that feel like they’re working as well as they can within the product already and build on them,” Cathcart says.

That means embracing such users as Mehal Kejriwal, an Indian dairy farmer and an enthusiastic WhatsApp user. Based outside Bangalore, Kejriwal’s company, Happy Milk, uses a Fitbit-style wearable for cows to track everything from how many steps each one takes to how long they sit.

Kejriwal relies on a business version of WhatsApp that now has 50 million monthly users, including 15 million in India alone, to run most of her business. She guesses that 90% of her communication with customers happens inside the app.

Happy Milk uses WhatsApp to send out business announcements, handle customer service issues, and even verify the legitimacy of its fresh, organic products. “They say you need three things to survive: food, shelter, and clothes,” she says. “But in India you need four things: food, shelter, clothes, and WhatsApp.”

Facebook sees Kejriwal’s business as an example of how it can make money from private messaging. It has even featured Happy Milk on its business blog. The model is especially attractive in markets such as Brazil, India, and Indonesia, where WhatsApp is already the standard communication tool for most people, and where advertising is less lucrative than in the U.S. or Europe.

WhatsApp plans to allow companies to list products for sale, gather orders through direct messages, and eventually accept payment for those orders. It’s possible a customer might first find Happy Milk through an ad on Facebook or Instagram, then make a purchase inside WhatsApp, a chance for Facebook to make money twice.

Right now, Kejriwal takes payments online through Google Pay or Paytm, a local payments competitor. But those methods require users to download a separate app. Putting payments into WhatsApp, which most people already have, will “remove a big roadblock,” she says.

Giving businesses and consumers a single place to handle all aspects of a transaction is tantalizing to Facebook, both as a new line of revenue and as a way to keep it relevant.

“If I’m Zuckerberg and I’m going to bed every night, what keeps me up? To me it would be that one day people wake up and they don’t want to use Facebook anymore,” says Mark Shmulik, an analyst with Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. Features such as shopping and customer service can give people a reason to open the app daily, he says. “They’ve been laying the groundwork here for a while.”

That doesn’t mean it’ll work. WhatsApp is leaning into an existing user behavior—more than 175 million people already message a business on WhatsApp every day, most of them outside the U.S., the company says. But that also means most of WhatsApp’s 2 billion users don’t yet do this, and Facebook is betting many will eventually adopt behaviors such as using the messaging app for payments.

It would also require regulatory approval in most jurisdictions, which has proven a challenge.

Earlier this year in Brazil, WhatsApp’s second-largest market after India, regulators ordered the service to pull its new payments offering just a week after it had premiered, demanding that Visa Inc. and Mastercard Inc. stop supporting the feature until it was properly reviewed for security issues and anticompetitive practices. In India, two years after the company started testing the feature, it’s still available only to a limited subset of users.

Still, executives say they’re encouraged by this progress. China’s WeChat, which allows users to buy everything from airline tickets to groceries, has proven that messaging services can successfully double as digital storefronts. WeChat dominates mainland China but has struggled outside the country, providing WhatsApp with an opening.

“There’s no doubt that India is a huge opportunity,” Zuckerberg said in July, adding that he was already looking at other countries. Who knows? The idea may even one day take hold in the U.S.

Cathcart likes to tell a slightly embarrassing story to illustrate how deeply private digital messaging has penetrated people’s lives. After the birth of his first daughter, Naomi, he discovered that he and his wife disagreed on how to pronounce her name, which they’d agreed on months earlier.

Even today, he calls her “NAY-omi”; his wife, “NY-omi.” “It took us a good month to figure out how we’d made that mistake,” he recalls. “And the realization was, every conversation about what to call her had been typed.”

WhatsApp isn’t Facebook’s only private messaging service. Many Instagram users rely heavily on its direct messaging function, and Facebook Messenger has 1.3 billion users. Facebook has experimented with some of the same commerce and customer service ideas in these apps as well.

Last year, Zuckerberg announced plans to integrate the messaging features inside all three apps, a massive technical challenge that would allow a user on one app to send messages to users on any of the others. While Facebook has discussed the shift in terms of user experience, it may also be harder to break the company up if its services are so intertwined.

Zuckerberg also plans to bring WhatsApp’s level of encryption to Instagram and Messenger, a part of his strategy to address concerns about Facebook’s previous privacy violations.

A shift from social media to private messaging would allow Facebook to trade some of its thorniest problems for new ones. If the company eventually makes a significant amount of revenue from service fees related to e-commerce, it won’t rely so much on gathering personal data.

If users are communicating privately via encrypted channels, it also reduces the burden on Facebook to moderate content, since it won’t even see what people are talking about. But encrypted messaging comes with its own set of controversies, since it makes it more complicated to police its service for criminal or other problematic activities.

WhatsApp has already experienced the dark side of this trade-off. In India and elsewhere, rumors falsely accusing people of crimes or inciting communal violence have spread in private groups, some with hundreds of members. In May 2017 four people were murdered in Jharkhand, India, after warnings about suspected kidnappers circulated on WhatsApp.

Two dozen people in the country were lynched in a matter of months in mid-2018 because of similar rumors spreading on social media, according to NPR. WhatsApp has since redesigned the app to make it harder to forward messages to other users, as a way to keep it from spreading panic.

Zuckerberg has said encryption’s drawbacks can be addressed. But his embrace of private messaging has been controversial at times within Facebook. Chris Cox, the company’s top-ranking product executive and Zuckerberg’s best friend, left the company in 2019 after more than a decade, in part because he worried about the negative impacts of encryption, a person familiar with the company said at the time. Cox, who spent a year and a half advising left-leaning political groups, has since returned.

Cathcart says encryption is vital to WhatsApp’s success. If the messaging service becomes a place where users do everything from debate baby names to buy milk, they need to feel secure doing so.

“People have reached a point where they communicate over messaging as if it’s face-to-face,” Cathcart says. “It would be so bad if someone found a way to read the messages someone sent, because everyone says something that’s sensitive.”