Facebook’s staff feel like they are under siege.

Every few days there seems to be a fresh accusation or leak that paints the social network in the worst possible light and calls into question whether it poses a threat to its members, wider society and even democracy itself.

The latest barrage came in the form of a tranche of “confidential” internal emails published online by MPs, who have been smarting that chief executive Mark Zuckerberg refused to testify before them.

As Damian Collins, the chair of the Parliamentary committee responsible, put it, if they could not get “straight answers” from Mr Zuckerberg then at least the emails could reveal how his firm treats users’ data and protects its “dominant position”.

Mr Collins claimed the documents prove that the social network continued giving some favoured apps access to users’ friends’ data after a cut-off point that was supposed to protect its members’ privacy.

He added that the emails showed the firm had also sought to make it difficult for users to know about privacy changes, and had surreptitiously studied smartphone users’ habits to identify and tackle rival apps.

Overnight on Wednesday, Facebook has published a blow-by-blow response to these and other allegations.

The main thrust of its defence is that the emails had been “cherry-picked” to paint a “false” picture of what really happened.

But does its counter-attack stand up?

White lists

One of the key apparent gotchas from the documents was Facebook’s repeated references to “whitelisting” – the process under which it grants special access to users and their friends’ data to some third parties but not others.

The context for this was that in April 2014, Facebook announced that it planned to restrict developers from being able to tap into information about users’ friends as part of a policy referred to as “putting people first”.

Until that point, any developer could build products that made use of Facebook users’ friends’ birthdates, photos, genders, status updates, likes and location check-ins.

While such access was to be cut off, Facebook said it would still allow apps to see who was on a user’s friends list and their relevant profile pictures.

However, if developers wanted this to include friends who were not using the same app, they now needed to make a request and pass a review.

New apps needed to apply immediately, and existing ones were given a year’s grace.

But Mr Collins said the emails demonstrated that some firms “maintained full access to friends’ data” after the 2015 deadline.

The documents certainly show several apps sought extended rights – although it is not always clear what the final outcome was.

But Facebook says it only gave “short-term” extensions to the wide range of information about friends and did so in cases when apps needed more time to adapt.

“It’s common to help partners transition their apps during platform changes to prevent their apps from crashing or causing disruptive experiences for users,” it explained.

In fact, Facebook already gave Congress a list in July of about 60 organisations to whom it granted this privilege, and said at the time that in most cases it was limited to an extra six months,

The names excluded some of the bigger brands referenced in the emails, including Netflix, Airbnb and Lyft.

The inference is that if they were indeed granted special long-term rights, it was only to access complete lists of friends’ names and profile images.

But since Facebook does not disclose which developers have these extra rights, it is impossible to know how widely they are offered.

Value of friends’ data

Facebook has long maintained that it has “never sold people’s data”.

Rather it said the bulk of its profits come from asking advertisers what kinds of audience they want to target, and then directing their promotions at users who match.

But Mr Collins said the emails also demonstrated that Facebook had repeatedly discussed ways to make money from providing access to friends’ data.

Mark Zuckerberg himself wrote the following in 2012: “I’m getting more on board with locking down some parts of platform, including friends’ data… Without limiting distribution or access to friends who use this app, I don’t think we have any way to get developers to pay us at all besides offering payments and ad networks.”

Facebook’s retort is that it explored many ways to build its business, but ultimately what counts is that it never charged developers for this kind of service.

“We ultimately settled on a model where developers did not need to purchase advertising… and we continued to provide the developer platform for free,” it said.

But another email from Mr Zuckerberg in the haul makes it clear that his reasoning for doing so was a belief that the more apps that developers built, the more information people would share about themselves, which in turn would help Facebook make money.

And some users may be worried that it was this profit motive rather than concerns for their privacy that determined the outcome.

Android permissions

Another standout discovery was the fact that Facebook’s team had no illusions that an update to its Android app – which gave Facebook access to users’ call and text message records – risked a media backlash.

“This is a pretty high-risk thing to do from a PR perspective,” wrote one executive, adding that it could lead to articles saying “Facebook uses new Android update to pry into your private life in ever more terrifying ways”.

In the conversation that followed, staff discussed testing a method that would require users to click a button to share the data but avoid them being shown an “Android permissions dialogue at all”.

Mr Collins claims the result was that the firm made it as “hard as possible” for users to be aware of the privacy change.

Facebook’s defence is that the change was still “opt in” rather than done by default, and that users benefited from better suggestions about who they could call via its apps.

“This was a discussion about how our decision to launch this opt-in feature would interact with the Android operating system’s own permission screens,” added the firm.

“This was not a discussion about avoiding asking people for permission.”

It previously defended its conduct in March after users had spotted saved call logs in archives of their Facebook activity and did not recall giving the social network permission to gather them.

Whether you accept its explanation or not, it does not look good that executives were clearly worried that journalists might “dig into” what the update was doing in the first place.

The risk is that this adds to the impression that while Facebook wants its members to trust it with their information, the firm has an aversion to having its own behaviour scrutinised.

Surveying rivals

Part of the way through the hundreds of text-heavy pages is a selection of graphs.

They show how Facebook tracked the fortunes of social media rivals including WhatsApp – which it went on to buy – and Twitter’s viral video service Vine – which it decided to block from accessing some data.

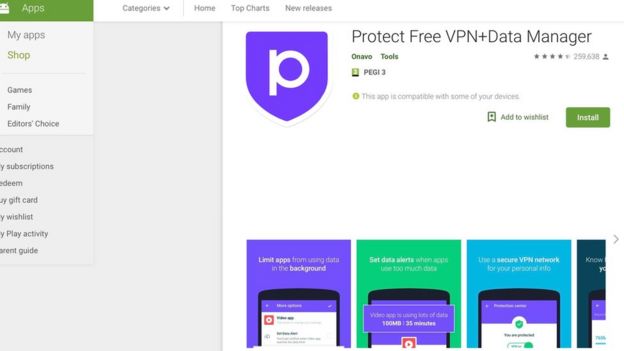

This tracking was done via Onavo, an Israeli analytics company that Facebook acquired in 2013 – which provided a free virtual private network app.

VPNs are typically installed by users wanting an extra layer of privacy.

Mr Collins accused Facebook of carrying out its surveys without customers’ knowledge.

Its reply was that the app contained a screen that stated that it collected “information about app usage” and detailed how it would be used.

It is true that the app’s privacy policy stated that it might share information with “affiliates” including Facebook.

But it is questionable how many of its millions of users bothered to read beyond the top-billed promise to “keep you and your data safe”.

In any case, if Facebook is not hiding anything it is curious that, even now, on Google Play the app continues to list its developer as being Onavo rather than its parent company, and only mentions Facebook’s role if users click on a “read more” link.

It is also noteworthy that Apple banned the app earlier this year from its App Store for being too intrusive.

Targeting competitors

You do not get to be one of the world’s biggest companies just by playing nice.

So, Mr Collins’ accusation that Facebook had taken “aggressive positions” against rivals is probably unsurprising.

Even so, it is interesting the degree to which Mr Zuckerberg is involved.

“We maintain a small list of strategic competitors that Mark personally reviewed,” disclosed one memo.

“Apps produced by the companies on this list are subject to a number of restrictions… any usage beyond that specified is not permitted without Mark-level sign-off.”

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESAs the case of Vine demonstrated, he is willing to take a tough line.

When asked if Facebook should cut off Vine’s access to friends’ data on the day of its launch in 2013 – ahead of the later wider crackdown – his reply was brief.

“Yup, go for it.”

Facebook suggests such behaviour is normal.

“At that time we made the decision to restrict apps built on top of our platform that replicated our core functionality,” it said in its response.

“These kind of restrictions are common across the tech industry with different platforms having their own variant including YouTube, Twitter, Snap and Apple.”

But it added that it now believes the policy is “out-of-date” so is removing it.

Too late for Vine, which shut in January 2017.

And Facebook’s problem is that politicians now have another reason for new regulations to limit anti-competitive behaviour by the tech giants.

Digital rights campaigners also have new reasons to gripe.

“Time and again, Facebook proves itself untrustworthy and incapable of building the world it claims it wants to see,” Dr Gus Hosein, from Privacy International, told the BBC.

“They show a pattern, fostered by market dominance, of deceptive and exploitative behaviour, which must be stopped.”