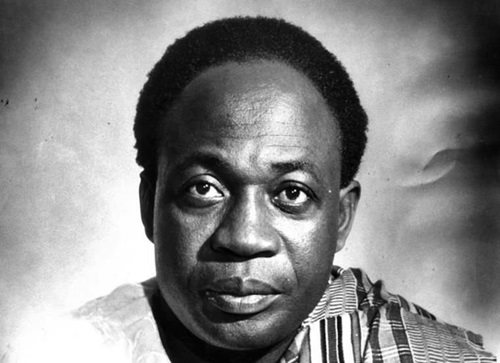

Kwame Nkrumah’s dream for Ghana was ambitious, yet its impact raises questions about whether it ultimately derailed the nation’s future.

From my study in Melbourne, I contemplate the legacy of Ghana’s first president.

The debate over the true founder stirs memories of my homeland’s journey. Each March 6, watching grainy footage of Nkrumah proclaiming Ghana’s independence –“At long last, the battle has ended! And thus, Ghana, your beloved country, is free forever!” – evokes pride and reflection on what might have been.

Today’s Ghana, seen through news and family conversations, still grapples with Nkrumah’s legacy, as his dreams, achievements and errors continue to shape the nation.

Historic

Nkrumah’s accomplishments were historic. He led Ghana to independence, and his pan-African vision inspired liberation movements across the continent.

His belief that “the independence of Ghana is meaningless unless it is linked with the total liberation of Africa” resonated beyond Ghana’s borders.

Reflecting on Ghana’s economic trajectory, I wonder how different things might have been if Nkrumah had chosen a more balanced approach.

A mixed economy, blending state planning with market dynamics, might have provided the stability needed for sustainable growth.

The abandoned factories from Nkrumah’s era, remind me of both the aspirations and limitations of his economic vision. However, cracks appeared in its execution.

Nkrumah’s embrace of socialism led to economic policies that haunted Ghana for years.

The state-controlled economy intended to rapidly industrialise the nation; it created inefficiencies and stifled entrepreneurial spirit.

Nkrumah’s industrialisation efforts, symbolised by projects such as the Akosombo Dam, aimed to transform Ghana from a raw material exporter into a diversified, modern economy. Yet, the emphasis on large-scale, state-run enterprises came at a significant cost.

The agricultural sector, Ghana’s economic backbone, was neglected, leading to declines in cocoa production and food shortages. Government control over agricultural pricing and marketing discouraged farmers, compounding production issues.

Moreover, the import substitution industrialisation (ISI) strategy, while initially fostering new industries, proved problematic.

Many industries were inefficient and reliant on imported inputs. This approach, coupled with expansionary fiscal policies, led to balance of payments issues and mounting external debt. Nationalising foreign-owned companies, though aimed at economic independence, deterred foreign investment, depriving Ghana of much-needed capital and expertise. State-owned enterprises became a burden rather than engines of growth.

Dire straits

By the time of Nkrumah’s ousting in 1966, Ghana’s economy was in dire straits. Foreign exchange reserves were depleted, inflation soared and national debt deepened.These economic challenges necessitated painful structural adjustment programmes in the 1980s and beyond.

However, placing all of Ghana’s economic woes on Nkrumah would be simplistic and unfair. His policies must be seen in the context of an era when state-led industrialisation was viewed as the fastest path to development. Some of his projects, such as the Akosombo Dam, have provided long-term benefits.

Politically, Nkrumah’s legacy is complex. His shift from independence hero to authoritarian leader serves as a cautionary tale in African politics. The Preventive Detention Act, allowing imprisonment of political opponents without trial, casts a long shadow over his democratic credentials.

Yet, labelling Nkrumah merely a dictator oversimplifies his actions, which were driven by a genuine belief that only through centralised control could Ghana achieve rapid development. This tension between visionary leadership and authoritarianism is one that Ghana, like many African nations, continues to navigate.

Reflecting from Australia, I see parallels with other post-colonial nations. Transforming a colonial economy into one serving a newly independent state is a challenge many countries have struggled with.

Ghana has learned hard lessons from its past, and its shift toward a market-oriented economy in recent decades has brought significant growth. Yet, the debate over the state’s role in the economy continues, echoing Nkrumah’s era.

The debate over Nkrumah’s legacy reflects Ghana’s broader struggle with its identity and future. Nkrumah’s supporters favour a state-led approach, while those recognising the Big Six lean toward market-oriented policies.

This polarisation oversimplifies Ghana’s complex history. Nation-building was a collective effort. To honour Nkrumah and others as Ghana faces new challenges, we must apply their courage and lessons.

Ghana has the potential to lead in African democracy, innovation, and development, but this demands critical engagement with our history and harnessing our people’s resilience and creativity.

The writer is an Associate Research and Teaching Fellow,

RMIT – Melbourne and Southern Cross University, Australia.