South Africa’s ban on alcohol during the coronavirus pandemic has prompted the BBC’s Vumani Mkhize to reflect on why he and his country have such a toxic relationship with drink.

I was a 17-year-old in my penultimate year at school when I had my first blind-drunk experience, which led to my expulsion in 2002.

I was returning to Ixopo High School in KwaZulu-Natal province, which is surrounded by undulating green hills so famously described by anti-apartheid writer Alan Paton in the seminal novel Cry, the Beloved Country.

Paton was actually a teacher there the 1920s and a handwritten first page of his novel hung in the school library. It made me want to emulate him – to have pages from a book I would write on the library’s walls. But that was before I got distracted.

Disembarking from the minibus taxi after the school holidays, my best friend and I took off our ties and blazers and headed straight to the town’s nearest bottle store where we bought two quarts of beer and a half-bottle of vodka.

The shop assistant had no qualms about selling alcohol to two wet-behind-the-ears boys, which says a lot about how negligent some establishments can be when it comes to serving underage children.

We drank behind an abandoned building – and I loved the feeling immediately, even if I wasn’t so enamoured with the taste.

By the time we dragged ourselves up the hill to the boarding school, it was dark and the gates were closed. The headmaster was summoned; our fate sealed.

I wish this had been the last such incident, but in the years to come I had many more blackouts and unseemly experiences.

But I felt no shame – I wore the blackouts as a misguided badge of honour, shared amongst friends while boasting how many cases of beer I drank in a weekend.

Apartheid-era drinking ban

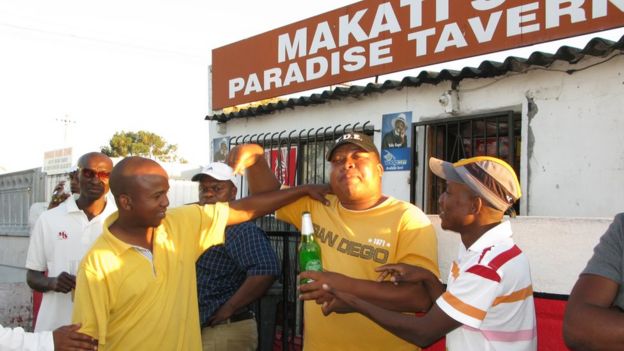

In the broader South African context my experience is not unique and I’m sure countless people will have more harrowing stories to tell.

The paradox when it comes to South Africa’s drinking culture is that while the majority of adults abstain, those that drink, do so heavily.

The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies the majority of drinkers in the country as binge drinkers.

This means around 59% of alcohol consumers drink more than 60g of pure alcohol on at least one occasion a month – that is six alcoholic drinks, four more than the daily recommended amount for men.

South African Medical Research Council’s Charles Parry, who has spent more than two decades researching the country’s fraught relationship with alcohol, believes there’s an inextricable link between our drinking culture and our past.![]() “There was a period of time when alcohol was not available to black South Africans,” Prof Parry tells me about the days before white-minority rule ended in 1994.

“There was a period of time when alcohol was not available to black South Africans,” Prof Parry tells me about the days before white-minority rule ended in 1994.

This led to drinkers going to illegal bars, with many black people seeing it as an act of defiance against the apartheid regime.

In the Cape Winelands, coloured (mixed-race) labourers were often paid in alcohol in what was called “the dop system”. Although long since abolished, the harmful legacy of that system is still pervasive in many coloured communities across the Western Cape.

While restrictions on alcohol in the past were largely based on racist policies, current restrictions are a matter of life and death.