Carving dignified role for chiefs in Ghana’s local governance (2)

The disagreement over the introduction of multiparty local governance still leaves open the question of specific modes of integration of Ghana’s traditional rulers into the local government system. Several options for integration have been proposed.

The 1992 Constitution does not automatically reserve seats in local government for chiefs. Article 242 (d) provides that not more than 30 per cent of members of the assembly should be appointed by the President in consultation with traditional authorities and other interest groups in the district. Most traditional rulers agree that they are never consulted. In practical terms, this means chiefs have no significant role in local government in the Fourth Republic.

Institutional representation

The National House of Chiefs (NHC) has consistently demanded institutional representation for chiefs as was the practice during the colonial government. Institutional representation entails actually reserving a proportion of the seats in local government for chiefs or traditional rulers without the necessity of contesting elections. The practice which was introduced by the colonial government continued after independence until it was abolished after the promulgation of Ghana’s First Republican Constitution in 1960. From 1961 onwards, chiefs were not entitled to a place in local government. The removal from power of the Nkrumah/CPP government, however, facilitated the re-introduction of institutional representation for chiefs. The 1969 Constitution reserved one-third of local council seats for traditional rulers exactly as was the practice in pre-independence period. In the Fourth Republic, the main demand of chiefs is for the 30 per cent of the seats set aside for government appointees to be reserved exclusively for chiefs. (CRC 2011, National House of Chiefs 2019).

Institutional representation for traditional rulers in local government originated in the colonial era and is very popular with chiefs. However, when chiefs and other citizens are put together in a debating chamber, the inevitable risk is that the chiefs could potentially lose the traditional reverence accorded them by their people, who in traditional terms are the “subjects” who should owe allegiance to them. When the multi-party local government is introduced after all the necessary constitutional amendment is passed, there could be the additional risk of chiefs being accused of partisanship, should their contributions in assembly debates get close to any party’s positions. In the end, the colonial origin of the idea of reserving seats for chiefs in local government could evoke feelings of public resentment in an independent and democratic republic of Ghana.

Alternate proposals

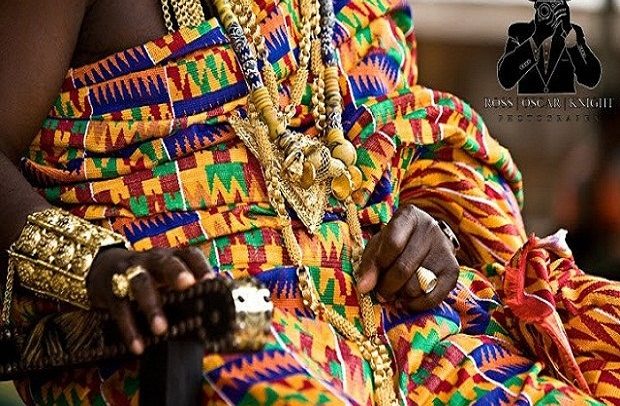

Chiefs and traditional rulers in general play crucial roles in the social, cultural, indigenous governance and development aspects of society that it is not prudent to leave them out of modern democratic governance. All aspects of community life revolve around the chiefs, a factor that accounts for the decision of the British Colonial authorities to construct a local government system around the chieftaincy institution.

In recognition of the central role of chiefs in the lives of their people, their position in a reformed local governance system must be substantive, pragmatic, functional, honourable and respectful. Direct institutional representation in a reformed local governance system, which is inclusive of parties, could expose chiefs to the risk of partisanship in debates. Any suspicion of partisanship on the part of chiefs could have the potential of eroding the reverence accorded the institution in society; hence, the alternate proposal for a Council of Local Development and Governance for each assembly.

Council for Local Development and Governance (CFLDAG)

It is proposed that a Council for Local Development and Governance, a structure backed by legislation, be created for every assembly. The council, comprising mainly of chiefs and queen mothers, will also have one or two local professionals, lawyers, doctors, engineers, accountants etc. as members. The council’s primary function would be to support and guide the assembly i.e., chief executives and assembly members in their development roles and take the lead in all conflict resolution. The council will be particularly supportive in land acquisition for district development and bring traditional wisdom to bear on the development of the districts.

The council should be fully funded by the budget of the assembly and membership will be determined by the traditional councils within the districts.

Benefits of CFLDAG

I. The CFLDAG will offer traditional authorities dignified, honourable, substantive and pragmatic pathway to effective participation in local development and governance.

II. The risk of direct participation in assembly debates and the potential charge of partisanship will be significantly minimised.

III. The CFLDAG will serve as an immediate and ready source of help and support for resolution of conflicts e.g., between MMDCEs and MPs, between MMDCEs and presiding members etc.

We conclude, therefore, that no reform of Ghana’s local governance would be complete without a clear definition of an honourable pathway for chiefs to play a substantive role. The dangers of direct institutional representation are clear to all and sundry. A Council for Local Development would afford the chiefs of Ghana a golden opportunity to contribute to local development and governance. As we say in many Ghanaian languages, we cannot tie a knot by passing the thumb. Our chiefs are our thumb in local governance, therefore, we should not by pass them.