Can Ukraine face another year of war?

Ukraine is losing the battle on the ground. Many of its soldiers are tired and exhausted after three years of fighting. The question – can the country endure another year of war?

Their forces are still resisting Russian advances in the east. But they’re almost surrounded near the town of Kurakhove – scene to some of the most intense fighting in recent weeks.

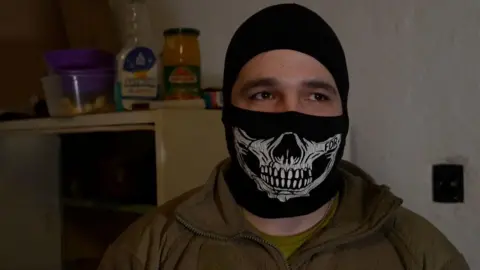

The Black Pack, a mortar unit, is trying to prevent their encirclement around Kurakhove. The Russian are closing in on three sides.

We meet the team at a safe house, getting a rest from the fighting. They’re not your average soldiers. They include a vegan chef, a mechanic, a web developer and an artist. A group of friends with non-conformist views. Some call themselves anarchists. They all volunteered to fight.

Surt, their 31-year-old commander, joined the army soon after Russia’s full scale invasion. He tells me at the start he thought the war would last three years. Now, he says, he’s mentally preparing himself for another ten years of fighting.

They all know that Donald Trump wants to bring an end to the war. Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelensky and Russia’s president have indicated they’re prepared for talks too, but the idea of workable deal seems hard to imagine.

So far, it is just talk about talks.

Surt is not dismissive of Trump’s goal.

“He is quite an ambitious person and I think he will try to do it,” he says. But he worries about the outcome of any negotiations.

“We are realists, we understand there will be no justice for Ukraine – many will have to swallow the fact that their homes are destroyed by rockets and shells, that their loved ones were killed, and this will be hard.”

When I ask him whether he’d prefer to negotiate or to keep on fighting – Surt replies emphatically: “Keep fighting.”

It’s a view reflected by most of the unit. Serhiy, the vegan chef, believes negotiations would just temporarily freeze the war – “and the conflict will return in a year or two.”

He admits the current situation is “not good” for Ukraine. But he too is ready to carry on fighting. Being killed, he says, “is just an occupational hazard.”

Davyd, the artist, thinks Trump is worryingly unpredictable. “He could be either very good or very bad for Ukraine,” he says.

The unit spends a week on the front and the next resting. But even when they’re resting they continue to train, because, they say, it keeps them motivated.

In a freezing field they go through the drills for firing their mortars. The team have recently been joined by Denys, who voluntarily left the safety of his home in Germany.

“I asked myself the question – could I live in a world where Ukraine doesn’t exist?” he says. He reluctantly admits it now appears to be losing, but adds: “If you don’t try then you will most certainly lose. At least I’ll die trying to win instead of just lying down and taking it”.

But, unlike the others, Denys says he thinks Ukraine should at least consider a ceasefire. He thinks Ukraine’s casualties are higher than those officially admitted – more than 400,000 killed and injured. Mobilising more of the population, he believes, wouldn’t solve the problem.

“I just think a lot of the motivated soldiers are either lost or they’re pretty damn exhausted – and so for me it’s not that we want a ceasefire, but we can’t go on for many more years” he says.

Dnipro, Ukraine’s third largest city, reflects that sense of war weariness too. It’s regularly targeted by Russian missiles and drones. The air-raid sirens wail intermittently, day and night. When they’re silent, Ukrainians try to find some sense of normality in these abnormal times – including by going to the theatre.

At an afternoon performance of a humorous play, called The Kaidash Family, there are still reminders of the war – a minute’s silence to remember the fallen, followed by Ukraine’s national anthem.

But some in the audience admit they’re also hoping for a longer-lasting release. Ludmyla tells me “unfortunately there are fewer of us. We’re getting some help, but it’s not enough – that’s why we have to sit down and negotiate.”

Kseniia says: “There’s no easy answer. A lot of our soldiers have been killed. They fought for something – for our territories. But I want the war to end”.

Opinion polls too suggest there’s increasing support for negotiations.

Some of the strongest calls for a ceasefire come from those who’ve been forced to flee the fighting. In a shelter near the theatre, in former student accommodation, a group of four elderly women reminisce about the homes they’ve left behind.

Eighty-seven-year-old Valentyna says they arrived with nothing, but have been provided with shoes, clothes and food. She says they’ve been treated well. “It’s good to be a guest, but its better to be at home.”

Her home is now in Russian-occupied territory. All four women want negotiations for peace. But Mariia, 89, says she doesn’t know how either side will be able to “look into the eyes of each other after the sheer hell they’ve committed”.

She adds: “It’s already clear no one will win militarily, that is why we need negotiations.”

If there are negotiations these women could end up having to sacrifice the most – as Ukraine may have to sacrifice land for peace.