Bright Simons writes: 17 Notes in Ghana’s 17th IMF Tune

News on Republic day (1st July 1960 was when Ghana ditched Queen Elizabeth II as Head of State) that Ghana is to return to the IMF for the 17th time in its history hit some nationalists and pan-Africanists very hard.

Members of the country’s ruling party who have bought wholesale into the government’s “Ghana Beyond Aid” mantra were also stunned.

For weeks, dark jokes about “Ghana Beyond Aid” transmuting into “Ghana Beyond Help” have been circulating in financial circles. The country’s vaunted “homegrown solutions” seemed incapable of stemming inflation or the slide in the national currency, the Cedi. No remedy seemed to be working.

Even the eLevy tax on digital financial services that the government burnt precious political goodwill foisting on a highly hostile public appeared to be performing at only 10% of expected yield.

The truth however is that many of the reactions to an IMF program are driven by notions of IMF behaviour that have long evolved. The IMF of today is not the IMF of the 1980s. If anything at all, it is the constant linking of IMF programs with abject economic management failure by the ruling party that has made going to the IMF such a doomsday scenario. A more nuanced analysis of modern IMF mechanics can be found in my previous essay.

In this brief follow-up essay, I outline seventeen (17) key points for this 17th attempt to salvage the Ghanaian economy through an IMF program.

1. Ghana waited too long to go to the IMF

Because of this delay, the twin debt-and-protracted-deficit crisis has become structural. Ghana is thus likely to qualify only for medium-term programs such as the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) or Extended Credit Facility (ECF). Both medium-term facilities come with higher conditionality than short-term and standby arrangements. In better circumstances Ghana could have qualified for a Flexible Credit Line (FCL) or a Precautionary or Liquidity Line (PLL). Were the problem strictly due to short-term shocks such as the Ukraine War and/or COVID-19 as the government insists, the IMF could also have offered a Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI) or a Rapid Credit Facility (RCF). Due to reckless overconfidence however the fiscal situation has deteriorated to a point where only an EFF or ECF is likely to be available.

2. IMF doesn’t like basket cases

Like every Lender, the IMF had rather not be dealing with a basket case. Ghana has for three years now been pretending that it is taking reforms seriously and that it has strong policies to address the issues that took it to the IMF in 2015. Instead, it has done very little to address weak institutions, poor spending choices and low public revenue growth. The wage bill continues to grow by nearly 15% year on year despite lip service to containment. The country has masked these weaknesses with lavish borrowing from yield-hungry local and international lenders. Evidence shows that countries with structural debt-and-deficit problems face more protracted negotiations with the IMF than those dealing with simpler balance-of-payments challenges.

3. Ghana has to brace up for the DSSI+ (Debt Service Suspension Initiative & its successors)

Between May 2020 and December 2021, the Bretton Woods institutions led a G20 process to offer temporary debt relief to countries struggling with their debt service load. Additionally, countries that qualified for the DSSI (it required a preliminary IMF program) were entitled to receive further support. 43 countries, many with far less onerous debt burdens than Ghana, benefitted from $5.7 billion in relief. Mysteriously, the Finance Ministry refused to allow Ghana to participate citing likely interference with the country’s commercial borrowing plans. Now that the DSSI window has closed, the government will be compelled to consider the G20 Common Framework. Chad, Ethiopia and Zambia recently asked for support under the Common Framework. The IMF’s attitude has been that these countries must apply the framework to structural reforms and not just debt service suspension or relief. Ghana may have to confront similar treatment soon.

4. The Hurdle of a “Staff Agreement”

Because of the Finance Ministry’s dismissive tone, the country has yet to prepare the all-important “Letter of Intent”, in which it must detail all the policy actions it intends to take to realise the goals of any IMF program.

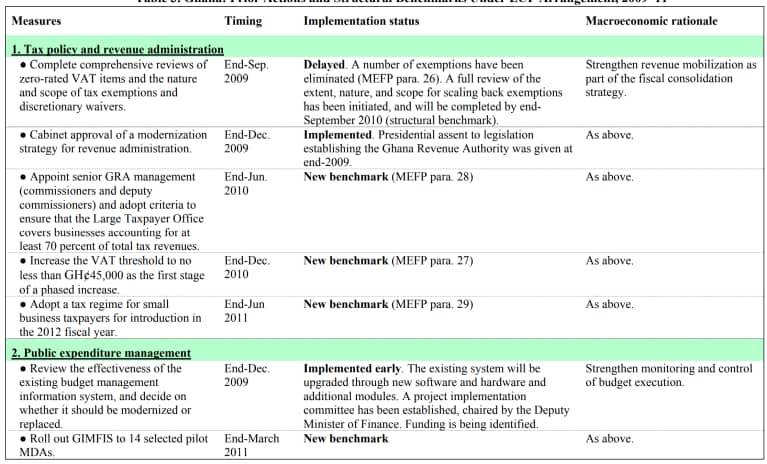

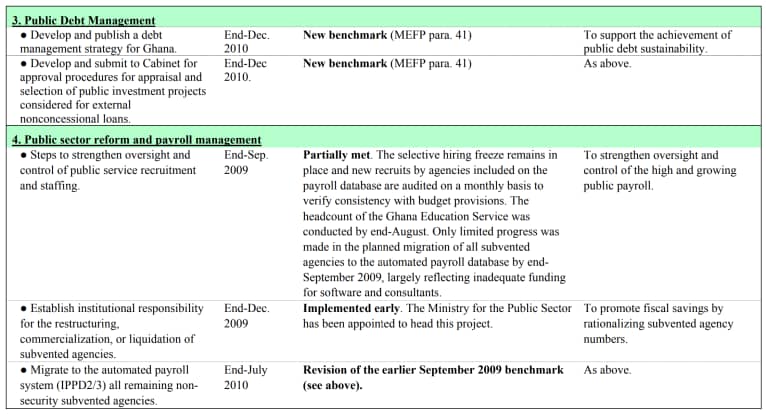

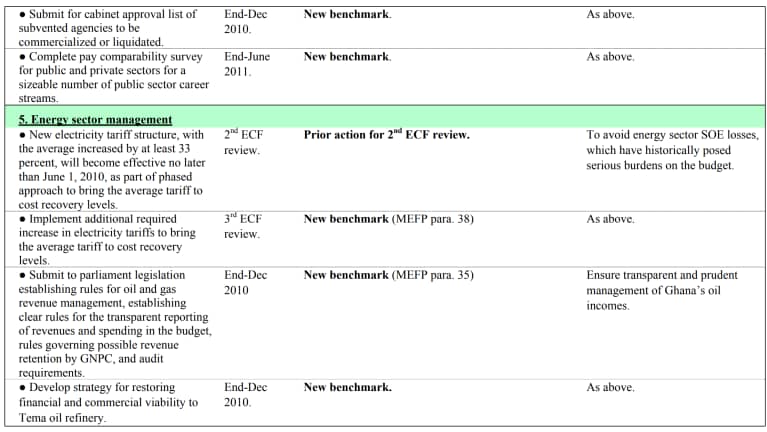

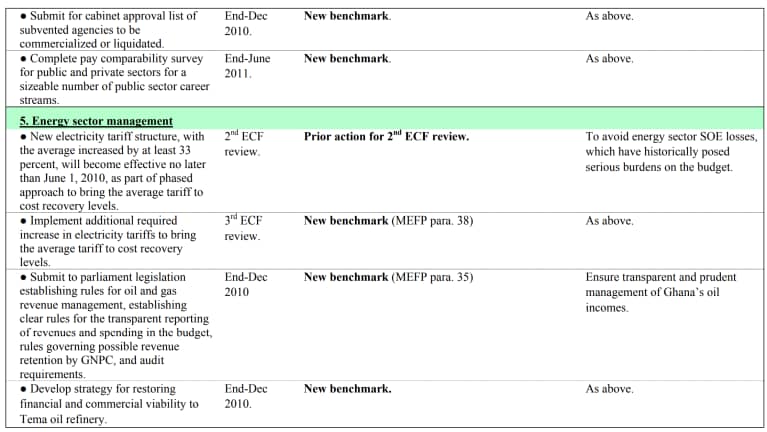

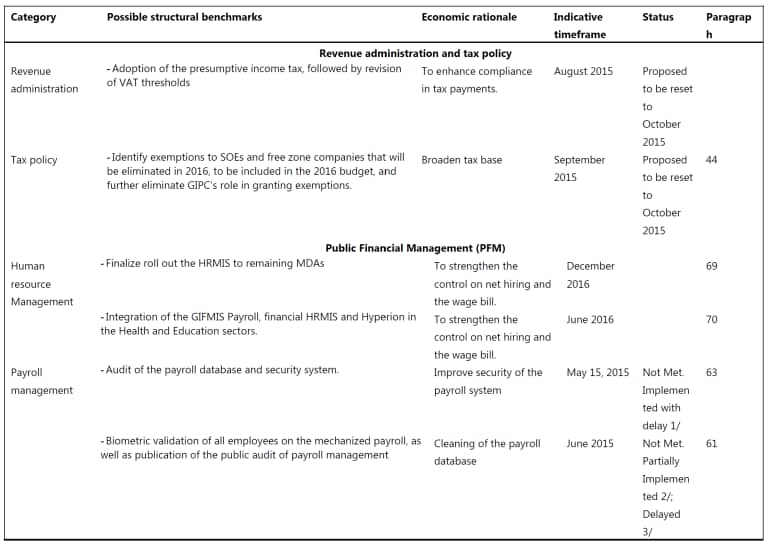

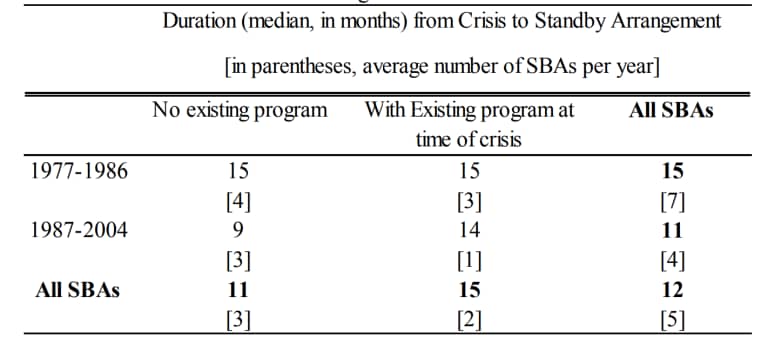

Below are the actions Ghana pledged to take during the 2009 to 2011 IMF (ECF) program timeline:

Note that the famous “hiring freeze” was already an element of domestic policy before the IMF got into the picture. It was government of Ghana which saw a slowdown in hiring as a means of “strengthening” the public service and embarked on it. When the time came to present a plan to the IMF in order to get their money and stamp of approval, the government said it would improve its implementation of the plan (because, as usual, the plan had up to then merely been on paper). It was not something the IMF sat in Washington DC to contrive and stuff down the government’s throat.

Readers also have noticed the government’s pledge to fix Tema Oil Refinery. It didn’t happen. Clearly, even with the IMF looking over its shoulder, the Ghanaian government routinely does not get done what it sets out to do.

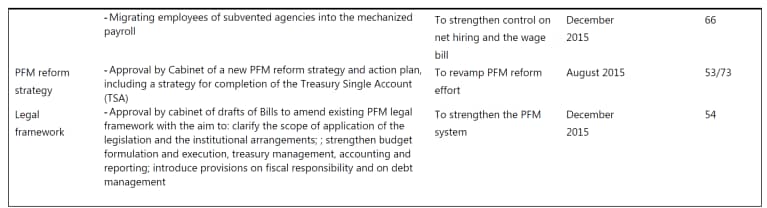

Below are the highlights of the 2015 program agreement as well.

Readers could not have missed the provision in the 2015 program to conduct an asset review of the banks. Most readers would recognise the important role played by the results of that review in the eventual effort to finally tackle the serious insolvency plaguing parts of the Ghanaian banking industry. One has to wonder why it has to take an IMF program for the authorities to deal with clear and obvious dangers.

A similar letter of intent now has to be prepared to commence the IMF dance. It would be reviewed jointly by the IMF’s country team, other analysts in Washington DC and the government’s own negotiators. The final details will make their way into a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), which will in turn detail the agreed performance targets for certain important macroeconomic phenomena as well as ceilings and floors for certain borrowing and spending activities of the government. Furthermore, the MOU will detail the disbursement schedule of any approved funds and what will trigger release. In past engagements with Ghana, IMF programs have nearly lost credibility because agreed targets and timelines have not been met as agreed. Because the MOUs also entitle the IMF to receive periodic data updates about a host of things, failure to report accurately and timeously can also cause friction. In 2018, when the last IMF program was in force, the government lied about its external arrears and was forced to write a humiliating apology.

In short, getting to the MOU stage (often called a “Staff Agreement”) entails clear commitments by the government to corrective actions that can address the scale of the challenge facing Ghana. It goes without saying that the bigger the challenges the bigger the commitments to reform the government must make and thus the higher the likelihood that IMF respondents might feel that promised actions do not go far enough.

5. Even a Staff Agreement is not the end of the road

Even after hammering out the terms of an MOU, the Board of the IMF still has to approve. Even after a program agreement is in force, disbursements may need further board approval. Kenya for instance is still waiting for board approval after IMF staff signed off on a disbursement in April. The IMF board, like all boards meet at scheduled intervals to address tabled matters.

6. Ghana needs a shorter-term remedy besides IMF

There have been reports in the banking industry of the government writing to lenders and holders of guarantees to provide extensions to timelines for due payments. The liquidity crunch facing the government is now so intense that this IMF announcement appears to have been made principally to give comfort to dithering prospective short-term lenders. The government has been chasing syndicated loans from commercial banks for a while now. Some of these banks have begun getting cold feet. Some have quietly told the government that an IMF agreement would make lending more palatable. This sudden u-turn in favour of IMF program is thus an attempt to seduce commercial borrowers. It would be wise for the government not to underestimate the markets and start looking for alternatives in cuts to discretionary spending. Equally daunting is how the government can sustain domestic debt servicing in the short-term without central bank financing. Current liabilities falling due this quarter significantly outstrip revenues. Analysts insist it is crunch time.

7. The more broken an economy the longer the IMF negotiations

Once a country waits till it is desperate before reaching out to the IMF, its situation takes on a character that cannot easily be fixed by medium-term liquidity improvements or even by restored access to the capital markets. Ghana has a credibility issue right now. It is not clear if it genuinely wants to reform its fiscal culture or merely wants a quick fix to restore access to the capital markets so that it can restart its borrowing spree. Recent IMF negotiations with countries like Sri Lanka shows a serious cynicism on the part of the Fund about these kinds of quick fix strategies because of its impact on the credibility of the IMF itself.

8. Ghana should be prepared for the possibility of protracted negotiations

Whilst the IMF has given a lot of hints that it would want to do a deal with Ghana, appetite for a deal is not enough. Even when an agreement is in hand implementation can be bogged down by policy and program disagreements, as has been the situation with Ethiopia since approval of a $1.5 billion program by the IMF Board in 2019. Similar issues have disrupted the $6 billion Pakistani program. It is noteworthy that Zambia continues to have program initiation challenges despite talks with the Fund dating from 2016.

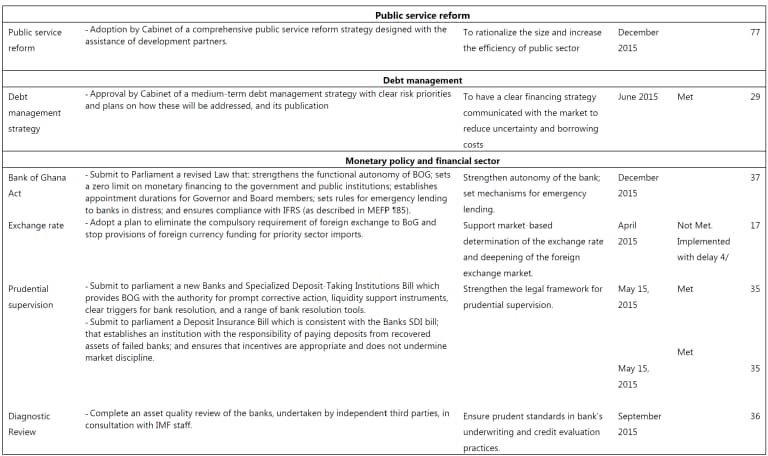

Researchers have tracked the time it takes the IMF, historically, to intervene in an ongoing financial or economic crisis. They have come up with an average of several months even for the relatively more straightforward standby agreements. Ghana’s year-long dilly-dallying fits this pattern.

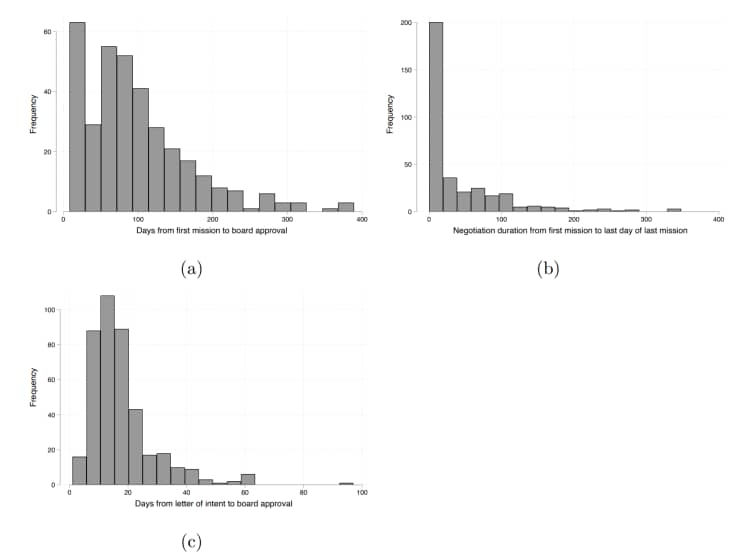

Once a Letter of Intent has been submitted by an IMF member state however (usually based on informal understandings reached with country staff), the decision speed improves considerably. Lauren Ferry and Alexandra Zeitz have computed an average of 115 days from commencement of negotiations to approval but a mere 20 days from the submission of a formal request to approval by the IMF Executive Board.

Most researchers report a strong correlation between the strength of a country’s United States (US) and European Union (EU) relationship and the speed of approval. Ghanaian foreign policy analysts generally rate current US – Ghana relations to be relatively less robust but fine enough. EU relations, on the hand, have been generally stable over a long stretch.

9. A Staff Agreement requires Ghana to accept facts it keeps resisting

A factor likely to influence the smoothness of Ghana’s IMF program initiation is the alignment between the Fund’s view of the Ghanaian fiscal situation and the Finance Ministry’s. One can glean from the routine country visit reports (the so-called “Article IV consultations” underpinning the IMF’s global surveillance mandate) some inklings of divergence between the IMF and the Ghanaian government on the right way to measure Ghana’s true debt position and deficit trajectory, especially in relation to the treatment of so-called “arrears”. Any decision to leave the negotiations solely to the same Finance Ministry mandarins who refuse to grasp the full scale of public liabilities could easily complicate the negotiations. The President should ensure representation from other ministerial and Jubilee House quarters.

10. Clarity on non-concessional funding

One of the biggest stumbling blocks ahead in the upcoming IMF journey is the government’s continued wish to source expensive loans to maintain its dead-end course for as long as possible. The interest rates on these loans are crazily high. The IMF is likely to take a very dim view of them.

11. All the more reason to stem the bleeding now

If showing good faith to the IMF might require a moratorium of sorts on securing ridiculously expensive loans at a time when the government is in desperate need of hard currency to service its international payments obligations, then now is the time to take a hard look at cash sieves like Kelni GVG which continue to bleed Ghana of millions of dollars every month for very little demonstrated return. To date, not a single independent report (not one commissioned by vendors or government agencies directly involved) has established the true benefits of programs like large-scale medical drone delivery, telecom revenue monitoring, fuel marking schemes and assorted government-driven ICT initiatives.

12. A proper spending review is now required

It is apparent from provisional fiscal data that the promised 20% cut across all public expenditure announced by the Finance Ministry was more rhetoric than cold reality. Public spending is actually expected to keep rising over the next quarter. Such a drastic austerity program as promised could not have been implemented anyway without a proper spending review conducted by truly independent-minded people in government. Unless the government is willing to cut loose pet projects of favoured officials and their cronies, such a spending review cannot proceed in good faith.

13. A spending review will have to take down ALL VANITY PROJECTS and perennial wasteful spenders

Should the prospect of an IMF program prompt a genuine spending review, courage would be required to take a knife to vanity projects like the flopped Liquefied Natural Gas initiative of the Ghana National Petroleum Corporation and various bungled flagship projects like One Village One Dam and One Million Cedis per Constituency etc. When a campaign was waged by civil society activists against the decision by the Electoral Commission to throw away nearly $70 million of perfectly sound infrastructure (including thousands of laptops that were then just over a year old), the government studiously refused to listen. Hundreds of millions of dollars have been wasted in a similar fashion across the government in support of various harebrained schemes.

14. Clarity on debt restructuring gameplan

Whilst the IMF announcement may have prevented another rating downgrade in the near-term, any prolonged delay in securing an agreement may actually trigger a downgrade. In a similar vein, whilst the initial reaction of investors to the IMF u-turn announcement has been positive, much of the sentiment is connected to hopes of an orderly debt restructuring deal with very minimal haircuts (cushioned with multilateral resources). Debt restructuring deals are very tough and time-consuming. Failure to present a clear narrative about strategy could easily turn expectations of a medium-term turnaround to fear of fiscal attrition and a disorderly default.

15. IMF toolkit is limited in scope and must be primed

The IMF’s toolkit for pre-emptive restructurings as a means of averting sovereign defaults is only viable with large doses of maximal transparency, sound tactical choices on reprofiling debt (even learning some lessons from interesting episodes like Belize’s), and a return to overall fiscal discipline.

16. IMF will not fix systemic governance deficits

Repeating any treatment for the 17th time cannot be an occasion for celebration. An IMF program is merely an opportunity to attempt a reset of specific fiscal dials. It does not transform national governance culture wholesale on any level. The eventual transformation of Ghana’s economy to one of sustainable growth and widespread prosperity cannot be delegated to technical interventions by international organisations.

17. The fight is still on the homefront

It shall only come about as a product of the nation-building struggle. IMF will come and go. It is not a savior from poor economic leadership. But neither should it be treated as a convenient scapegoat for homebrewed failures. The fight for true economic liberation remains that of Ghanaian citizens alone.