Meeting chiefs of the Nzema area this week, Ghanaian President, Akufo-Addo, pledged to amicably resolve the increasingly protracted impasse between one of the country’s local oil companies, Springfield, and a consortium made up of Italian oil major, ENI and its Swiss partner, Vitol.

Attempts by the Government of Ghana to force a “merger” of the separate petroleum discoveries of Springfield, on the one hand, and Eni and Vitol, on the other hand; split the equity of the merged “unit” anew among the companies; and have them jointly produce oil from the combined field is in stark contrast to the voluntary agreement that led to a similar “merger” (or technically, “unitization”) of the country’s most successful oil field to date, Jubilee.

In the case of Jubilee, the oil companies involved (Tullow, Kosmos, Anadarko and others) agreed that the discoveries they had separately made on the concessions separately leased from Ghana were indeed connected in such a manner that it would make sense for the discoveries to be unitized and produced as a single oil field.

In response to the Government’s attempt to impose a formula for a forced unitisation of the fields, Eni-Vitol have decided to trigger the dispute arbitration clause in their lease agreement with the Government. A showdown at the London Court of International Arbitration between Ghana and the Swiss-Italian investors is now imminent.

Usual Justifications for Unitisation

The benefits from unitization are usually spread among the producing oil companies/investors, the Government and the host country.

Because petroleum (oil, gas and other economically valuable derivatives) is often trapped underground or under the seabed (all of Ghana’s commercial discoveries so far are “offshore”, under the seabed) in fluid forms, the “accumulation” can shuffle around the rock formations in which it is trapped.

Concessions are often given out without a full picture of how the petroleum is distributed under the seabed, though with every seismic mapping done by investors the country knows better how to carve out the concession blocks for block lessees to minimize such “straddling” of petroleum reservoirs.

When investors enter into contracts with Ghana to lease a block under the sea (under international law, Ghana controls its coastal seabed, or continental shelf, up to an extent of 200 nautical miles or more into the high seas), they do so with the hope that any “pool” of petroleum they discover in any section of the block that they can drill profitably will be theirs to own and exploit.

They will usually also have the right to invite investors to share the costs and profits (i.e. “to participate”) resulting from the eventual harvest of hydrocarbon riches (of course, by law and through negotiation, the Government is entitled to about 10% more or less of any such discovery, usually exercised through the Ghana National Petroleum Corporation – GNPC – or one of its even more commercial subsidiaries, such as Explorco or Gosco).

If it turns out that the pool of oil extends to adjacent blocks, then there is the possibility that the oil in one block can be “suctioned out” by the oil companies who own the adjacent blocks faster or in larger quantities, draining the pool or reservoir to the detriment of the slower or more cautious block owner. To prevent such a fate, each block owner is incentivized to drill as aggressively as they can (so-called “competitive drilling”) leading to suboptimal decisions in many ways.

Because effective drilling requires careful management of the pressure in the reservoir, one has to position production wells carefully in order to apply just the right amount of force on the right points in the overall “geological structure” or “stratigraphic trap” in which the petroleum has accumulated. A common reservoir thus require a central design.

Often, additional measures are needed to engineer the pressure dynamics, such as injection of water and gas at specific points to build up pressure for the petroleum fluids to flow up the production wells through “risers” into production facilities (such as so-called “FPSOs” or “submersible rigs”) on the sea surface. Siting these expensive but non-producing “injector wells” properly often requires that the field engineer takes into account where the production wells are also placed. Without a central field engineer, individual block owners would usually favour more production wells on their side than injector wells that optimizes pressure across the entire reservoir.

All of these suboptimal decisions – competitive drilling, poor siting of wells, underinvesting in secondary recovery infrastructure like injectors, etc – impact the long-term performance of the oil field. Investors, as a collective, may lose out because of duplicative spending on competing wells and injectors. Government loses out on revenue because most capex costs by investors are tax deductible. And the society loses out since in the medium term less oil and less oil revenue are generated for socioeconomic returns (jobs, social spending, contracts for value chain companies etc).

Unitisation is However Not Always the Only Option

It is important to bear in mind however that some of the problems that unitization usually sets out to solve can be addressed through other regulatory means. For example, every well that is sunk in a block usually needs prior regulatory approval. In fact, some operators in Ghanaian waters claim that the total number of approvals needed to get a new oil field going exceed two thousand. The regulator has a say in well spacing decisions through its ability to coordinate the outcomes of multiple “plans of development” for oil fields submitted by different companies in adjacent contract areas.

Companies can also embark on what is known as “pooling” whereby they co-invest in oil wells with regulatory approval in order to minimize the duplicative spending of drilling unnecessary adjacent wells. With horizontal drilling and sidetracking techniques getting more sophisticated by the day, such commercial solutions are even more viable today than they were in the past. The broad term for these other alternatives to unitization is “joint development”.

As a last resort, regulators can even cap production output to prevent excessive drainage of the reservoir. In the present case of Eni, the initial production forecast of 45,000 barrels of oil a day has been significantly exceeded (peak production is now at 57,300 barrels) because this is allowed.

The above caveats notwithstanding, unitization is usually a preferred mode for maximizing recovery when legal and regulatory certainty is required.

Why the Eni – Springfield Impasse then?

Given the potential benefits to investors and block owners/lessees of unitization and the usually voluntary nature of the practice (some jurisdictions like Texas don’t even have a statutory pooling or compulsory unitization regime), why has the Eni-Springfield matter become so acrimonious?

It is clear from the title of this explainer which way my sentiments turn. I think GNPC is the problem. But to make the case properly, it is important to trace the long genesis of the two oil discoveries that the Government of Ghana wants developed as a single unit.

The Eni – Vitol Sankofa Discovery

In March 2006, the Government of Ghana signed an agreement with Heliconia Energy, for the Offshore Cape Three Points block. As is customary in this space, Heliconia flipped the block to Vitol, the parent of its own Bermuda holding company, Atlantic.

In 2009, Vitol struck gas in the area of the block which became the Sankofa oil field. As is customary in this industry, Vitol sold a piece of the block to Eni, in the process sharing the financial risk and enabling an injection of further capital to develop the block towards production. With further exploration, oil was also discovered in the area in 2012.

Three years later, the World Bank provided political risk guarantees totaling $700 million (believed to be the largest ever such commitment by the Bretton Woods institutions to a capital project). Further loans from the IFC and other parties to Vitol and Eni underwrote a program of investment leading to oil production in 2017 and gas production in 2018. The World Bank estimated total project costs at $7.7 billion (of which it was responsible for mobilising about $1.27 billion). Eni, on its part, has reported total expenditure to date of $6 billion, and a revised project life-cycle capital expenditure of $10 billion.

The Eni consortium companies see themselves as deserving credit for having brought the biggest single overseas investment to Ghana to develop a risky and highly complex asset.

The Springfield Afina Discovery

In the same 2015 that the Eni consortium began drilling operations following the earlier approval of the plan of development by the Government in 2014, the Springfield upstream story began in earnest.

Two years earlier, in December 2013, Kosmos Energy had to give up a part of the West Cape Three Points block because under Ghanaian law a company is time-bound to explore for oil and develop any quantity found, or it must relinquish parts of the block on which it has not hit commercially exploitable oil.

The 1.37 square kilometers of seabed given up by Kosmos in this fashion was split into two new blocks and companies invited to bid for both. About 12 companies expressed interest, Springfield being one. In April of 2014, Springfield was thus allowed access to the GNPC data room to evaluate the cumulated data on the block gathered by previous lessees.

Springfield came to GNPC with the Taleveras Group, a company part-owned by Nigerian tycoon, Igho Sanomi. In June 2014, Taleveras was introduced as the technical partner that will operate any blocks awarded the consortium. Unfortunately, soon thereafter, Taleveras began to experience serious financial challenges, culminating in a string of legal actions around the world. Not surprisingly, the Evaluation Committee disqualified it as the Technical Operator for lack of relevant experience and financial capacity, and decided to limit Springfield’s bid to block 2 alone.

Hence, in October 2014, Springfield introduced a new Technical Operator, Vaalco Energy, a small, Houston-based, Gabon focused oil junior. Vaalco had some requisite experience (it was Hunt’s partner during a small seismic campaign in Ghana as far back as 1999) and was thus acceptable to the Committee. But just before the Committee could complete its evaluation, Vaalco also decided to pull out as the Technical Operator.

Here is where Springfield’s exceptional tenacity comes into the picture. They convinced the Committee and the Ministry of Energy to award them the block nonetheless pending the onboarding of a Technical Operator. The Committee agreed and in turn convinced Parliament to ratify Springfield’s Petroleum Agreement with the Government, but with a caveat. Springfield was asked to find a Technical Operator within a year. The Ghanaian model contract gives an oil company 7 years to find oil anyway, with room for extension under certain conditions.

Springfield succeeded in convincing the Ministry of Energy and the GNPC to allow it to continue to explore the block without a Technical Operator on the basis that oilfield services contractors, like Schlumberger, will more or less play that role despite the lack of official designation. Furthermore, it had set up a technical services company itself called Fairfax and also intended to form a joint venture with Aker Solutions, the Norwegian equipment player, to explore capacity development for exploration and production.

After a 3D seismic mapping exercise involving the giant Ramfom Titan in 2017, it secured the necessary regulatory approvals for drilling. Now primed, Springfield secured a rig to drill two wells in August 2019. The initial plan was to mirror a discovery in the adjacent ENI block (discussed above) called Beech by targeting a well named Oak-1x before targeting the Afina-1x well. Somehow, the campaign was reduced to just one well, Afina, and after 64 days of drilling, the targeted depth was reached in November 2019.

False starts notwithstanding, just before Christmas 2019, Springfield announced with massive fanfare the discovery of 1.5 billion barrels of oil in its budding Afina field.

No doubt that Springfield sees itself as a highly tenacious, groundbreaking, visionary African oil pioneer that will stop at nothing to realise its dream to become the first African operator of a massive ultra deepwater block.

Legal & Engineering Best Practices

After a new oil find, Ghanaian law requires oil companies to “appraise” it. This is such a critical point in this story that it merits quoting the relevant portion of the law. Appraisal is defined as:

“operations or activities carried out …following a Discovery of Petroleum for the purpose of delineating the accumulations of Petroleum to which that Discovery relates in terms of thickness and lateral extent and estimating the quantity of recoverable Petroleum therein, and all operations or activities to resolve uncertainties required for determination of a Commercial Discovery”.

It is worth noting the boldened portion of the definition above as a major part of the dispute arbitration commenced by Eni-Vitol may well turn on the meaning of this sentence.

More so because the famous Article 8 of the model Petroleum Agreement sets conditions for unitization hinged on this basic prerequisite (various relevant extracts):

“As soon as possible after the analysis of the test results of such Discovery is complete, and in any event not later than one hundred (100) days from the date of such Discovery, Contractor shall by a further notice in writing to the Minister, the Petroleum Commission, and GNPC, indicate whether in the opinion of Contractor the Discovery merits Appraisal.

“Where the Contractor does not make the indication required by Article 8.2 within the period indicated or indicates that the Discovery does not merit Appraisal, Contractor shall, subject to Article 8.19, relinquish the Discovery Area associated with the Discovery.

“In the event a field extends beyond the boundaries of the Contract Area, the Minister may require the Contractor to exploit said field in association with the third party holding the rights and obligations under a petroleum agreement covering the said field (or GNPC as the case may be). The exploitation in association with said third party or GNPC shall be pursuant to good unitization and engineering principles and in accordance with International Best Oil Field Practice.

“Where Contractor indicates that the Discovery merits Appraisal, Contractor shall within 180 days from the date of such Discovery (or, in the case of the Existing Discoveries, within nine months from the Effective Date) notify the Minister and submit to the Petroleum Commission for approval and to the Minister for information purposes a Proposed Appraisal Programme to be carried out by Contractor in respect of such Discovery.”

Here too, the boldened text – “good unitisation principles & international Best Oil Field Practice”, is the fulcrum around which the arbitration about to commence in London will turn.

Is Afina a commercial discovery? Are the directives by the Minister for the ENI consortium and Springfield to compulsory unitise their separate finds on grounds of “straddling” following International Best Oil Field Practice? Can a find that has not yet been established as commercial through appraisal be made part of any other arrangement considering the language of the provision?

Obviously, it would be imprudent to make categorical pronouncements now that the matter is in arbitration. But we can explore certain critical aspects to gauge whether things should even have been allowed to go this far.

The Fracas Begins

The complications arose a few months after Springfield’s announcement in December 2019 that it had made a massive find containing 1.5 billion barrels of oil. A field containing that amount of oil is, with virtual certainty, a commercial discovery.

Whilst the determination of whether an oil find is commercial is driven by multiple factors such as the prevailing oil price, the complexity of the reservoir (which will impact costs) and the distance to production facilities or need for totally new infrastructure, volumes and the certainty of recovering those volumes are by far the most commercially sensitive parameter.

Springfield’s initial estimate of 1.5 billion barrels was followed by a claim that the find it had made is in fact connected to the Sankofa East field in the ENI consortium’s block (Springfield would later reveal that it had suspected this from geophysical analysis since 2018).

Following a formal application by Springfield for unitization, the Minister of Energy, on 9th April 2020, issued a directive pursuant to Section 50 of the 2018 petroleum regulations requiring Eni and Springfield to unify their finds.

The interesting thing about Section 50 is that it does not elaborate on the preconditions of commerciality mentioned in the Model Petroleum Agreement nor does it touch on the role of appraisal in establishing the equity split (or “unit interest”). It primarily focuses on the Minister’s powers to issue model contracts specifically for unitisation.

Eni insisted that both appraisal and commerciality were critical factors in any unitization process and refused to budge. So, on July 29, 2020, the Chief Director of the Ministry of Energy wrote a second letter to the two companies lamenting their refusal to share data and the general lack of cooperation.

Springfield says that it persistently pursued ENI for a meeting with scant results. Vitol, the other main half of the ENI Consortium, responded to the Ministry that Springfield had already proceeded to the High Court in an attempt to enforce the order to unitise.

On 19th August 2020, the Minister again wrote to the ENI consortium that it is engaging an independent third party to review the claims of the two parties and will impose the findings once they were ready.

Meanwhile, the parties had so far failed to sign a confidentiality agreement for data exchange to commence. Consequently, on 14th October 2020, the Minister imposed conditions for the unitization. Eni and Vitol continued to insist that as far as they were concerned the basis for unitization had not been established by sound engineering principles and data.

It is critical at this juncture to establish that whilst the Minister’s 14th October order imposing terms for the unitization was based on a 6th October technical report by the GNPC, his 9th April order appears to have been triggered primarily by the Springfield application without any comprehensive technical evaluation of the latter’s claims.

Readers would notice that the October 14, order was merely laying out terms, including crucial determinations about unit interest (how much equity two parties – ENI+Vitol and Springfield – stood to gain in the unitized field), for a directive that had already been made.

It will weigh heavily on the minds of the arbitrators that the substantive 9th April directive itself was made before an independent technical evaluation of the claims of Springfield in its application for unitization to the Ministry claiming that its Afina find was connected to ENI’s Sankofa East field.

The Arbitrators are also likely to ponder if GNPC, an entity with commercial interest in the fields in contention could be considered an “independent third party” to provide a technical assessment that could rewrite the commercial rights and entitlements of its partners.

With those important observations in the background, we can now turn to the 6th October technical report from the GNPC based on which Ghana decided to divvy up a future combined Sankofa-Afina field between Eni-Vitol and Springfield, with Springfield getting a majority of 54.5%.

Illustrative Chart of the Equity Split Imposed by Government on the Future Combined Field

| Block Owner/Lessee | OCTP Participation (%) | WCTP-2 (New Discoveries)* Participation (%) | Total Unit Interest (Sankofa-Afina Merged Unit) |

| ENI | 44.44 | ~17.5% | |

| Vitol | 35.56 | ~14% | |

| GNPC | 14 | 11 | 10% |

| Explorco | 5 | 5 | 4% |

| Springfield | 84 | 54.5% |

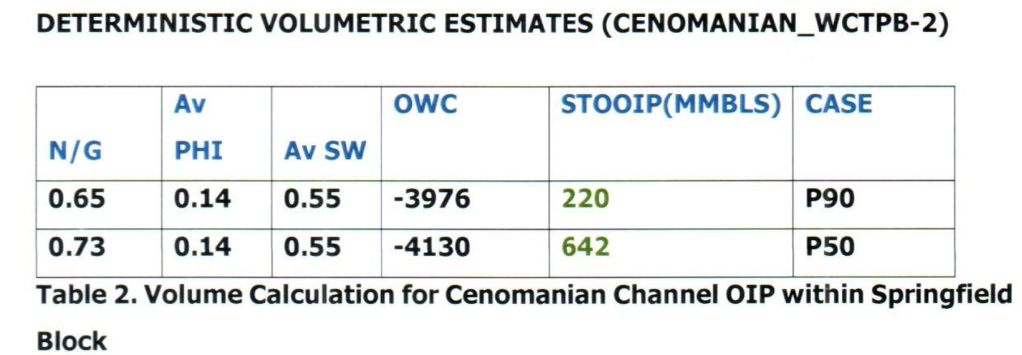

The GNPC report asserts in its executive summary that the two finds – Eni-Vitol’s Sankofa East and Springfield’s Afina – are indeed connected (both emanate from a common reservoir straddling their separate blocks). It also states that based on analysis the P90 case (the lower bound of estimates or the quantity that has at least a 90% probability of being produced or exceeded) for how much oil is in the Springfield side of the common reservoir is 290 million barrels, whilst the mean case puts the oil in place at 642 million barrels (revised upwards from the 506 million barrels estimated from earlier 3D seismic analysis).

Extract from the fateful GNPC 6th October Report

The important matter here is the applicability of the International Good Oilfield Practice (IGOP) requirement in Ghana’s petroleum regime as indicated in earlier sections. The classification of reserves by probabilistic scenarios like P10, P50 and P90 is not an arbitrary process.

It follows well laid down IGOP guidelines in the Society of Petroleum Engineers framework for classification. Such guidelines are of course are the types of doctrines and principles constituting the bedrock of Lex Petrolea, or international petroleum law, the domain of norms governing the ongoing Eni-Vitol – Government of Ghana dispute arbitration currently underway in London.

The key issue in reserves classification, as a matter of global practice, is the narrowing of uncertainties and unrisking. In this discussion, we have witnessed a progressive narrowing of Springfield’s initial communication of P50 reserves of 1.5 billion barrels of oil in place to GNPC’s estimate of 642 million barrels in place.

Eni’s corresponding P50 number of 535 million barrels in place, on the other hand, has gone up from an earlier estimate of 450 million barrels of oil equivalent (BOE) in 2013 to 535 million BOE after 20 wells drilled and consistent production of more than 3 years.

The question that will weigh on the minds of the arbitrators is whether GNPC’s approach to P90 and P50 classifications are solidly grounded seeing the wide uncertainty ranges on display.

All this while, due to the disagreements over confidentiality, Eni had not actually received the information based on which these determinations by GNPC and the Ministry were being made. Finally, on 23rd March 2021, the Minister decided to instruct the Petroleum Commission to hand over the data on Springfield’s Afina to Eni under a confidentiality agreement signed with the Commission (as opposed to Springfield).

On 26th April 2021, Eni and Vitol (for simplicity sake, we shall sometimes refer to the Consortium simply as “Eni” going forward) concluded its analysis of the data and submitted a report containing a startling claim to the Ministry: in its view, Springfield’s Afina find is so small it may not even be commercial after all (i.e. it may not be economically profitable to be produced).

Because Ghanaian law does not require finds made in two adjacent blocks to be directly connected before a finding can be made that they are best produced as one field, the technical debate till then had focused on whether there was even any merit in the investigation into whether Afina and Sankofa were really linked geologically. The dimension of non-commerciality now took center-stage and shook up the premises of the debate.

Eni’s analytical posture in the 26th April report starts with a sketch of the geology of the border between the two adjacent blocks. Per this analysis, the closer one moves westward from the Sankofa East area to the Afina find area, the poorer the petrophysical properties became reducing to an extent the likelihood of the presence of a continuous geological structure.

Accordingly, Afina, compared to Sankofa East, has much greater mud contamination in its hydrocarbon columns. Thus, whilst the rocks in both fields may be of similar origin and could have matured through time by means of similar geological processes, the evidence, says Eni, does not confirm that the two reservoirs are actually connected.

In line with these arguments, Eni then brought up the issue of why the Afina well has so far not been tested. After all, the flow rate would have helped further reduce the uncertainties involved. Bearing in mind that on average 5 wells are drilled to establish commerciality in many similar contexts, to use one untested well as the basis for firm estimates is pushing the envelope.

A more technical argument related to why certain production activities on the Eni side were not impacting on pressure observations on the Afina side. But by far the most aggressive claim in Eni’s 26th April report was the assertion that rather than the GNPC estimate of 642 million barrels of oil in place in the P50 case, a more reliable estimate would be 94 million barrels, which under present conditions may not even be worth developing for production.

If Eni really believes this, it is completely ridiculous for anyone to have assumed on the Government of Ghana side that any amicable solution could be found whilst compulsory unitisation was still on the table. Below is a very crude calculation that nevertheless illustrates the commercial impracticality of expecting either Springfield or Eni to play ball along conventional unitization lines.

For reasons of simplicity, the calculation looks at the nominal value (without accounting for inflation or the time value of money) of the oil in the two adjacent fields. It also ignores production costs in both the status quo scenario and the scenario in which the unitization proceeds. Whilst it far from an NPV+ calculation, it still serves the purposes of illustration fairly well because it is strictly from Eni’s view, and thus assumes no savings from unitization.

Eni’s Oil-in-Place Nominal Valuation Scenario

| Block Owner/Lessee | Total Unit Interest (Sankofa-Afina Merged Unit) | Nominal Economic Value of Interest Post-Unitisation | Economic Value of Interest Pre-Unitisation | Economic Impact of Unitisation |

| Eni | ~17.5% | $5.162 Billion | $11.11 Billion | -$5.948 Billion |

| Vitol | ~14% | $4.13 Billion | $8.89 Billion | -$4.76 Billion |

| GNPC | 10% | $2.95 Billion | $2.95 Billion | 0 |

| Explorco | 4% | $1.18 Billion | $2.43 Billion | -1.25 Billion |

| Springfield | 54.4% | $16.07 Billion | $3.78 Billion | +12.29 Billion |

From Eni’s standpoint the unitization is heavily tilted towards Springfield and offers it nothing besides nearly $6 billion in asset losses. Together with Vitol, it stands to lose nearly $11 billion should the unitization proceeds. While Ghana would like to couch the forced unitisation as a technical regulatory matter, the prospect of large financial losses invokes some comparisons with expropriation, a well travelled area in the growing body of Lex Petrolea.

In the same vein, Springfield stands to gain more than $12 billion in this scenario. Since none of the current unitisation models on the table contain a scenario in which Springfield is worse off, it stands to reason that Springfield will stand its ground. Its position is perfectly logical.

GNPC, the House of Supreme Incompetence

The conduct of the private companies is completely understandable from a cursory review of the scenarios above.

If GNPC’s view is correct and Springfield’s Afina has 642 million barrels, Springfield gets its just share from the initial tract participation (i.e. the equity split of 54.5% – 44.5% in its favour) but if Eni’s more pessimistic view turns out to be right, Springfield gets a $12 billion windfall.

Whilst the Minister’s terms includes the standard “redetermination” provision, whereby these equity splits/unit interests could be revised in light of new data, within an 18-month timeline, the order falls far short of international best practice in how redetermination of international tract participation is to be managed.

First, a Preliminary Unitisation Agreement would normally be constructed very differently from the outright Unit and Unit Operating Agreement the Minister sought to impose through his order. Such an agreement will seek to establish the full extent of the common reservoir in order to determine the Initial Tract Participation (ITP). The ITP would not be imposed as a fait accompli prior to any Preliminary Agreements on the approach to embarking on the road to unitisation.

Second, a cost sharing provision would be necessary at the preliminary level to cover the additional costs of reservoir modeling. Under no circumstances, judging from the picture that emerges from a scan of dozens of relevant case studies in IHS’ commercial PEPS databases, can a pre-unitisation agreement (PUA) even be entered into without preliminary agreements on joint data collection, which in this case would include some appraisal work. It is the PUA that sketches both the “unit interval” and the initial unit interests for subsequent confirmation. Not arbitrary reports by National Oil Companies aiming to short-circuit the path to a Unit & Unit Operating Agreement (UUOA).

It is also the PUA that establishes the working groups within the context of mutual trust and confidence to enter serious discussions for final unitization. One of the key tasks facing such a working group (for example, a Pre-Unitisation Operating Committee) is the thorny issue of historic capex that would have contributed to the overall commerciality of the combined field. In this case, we have one field that has already incurred costs in excess of $6 billion. The Minister’s directive by focusing purely on historic production numbers without addressing historic capital expenditure showed considerable misunderstanding of the issues at stake.

Another source of confusion is the lack of clarity on the role of truly independent experts in the redetermination process. We can dismiss out of hand the notion of a National Oil Company serving as both participating interest holder and an independent expert offering mediation services in a fraught matter such as this.

In a situation, such as this one, where the Joint Database of production and appraisal data reflects activities to prove reserves by one party and almost none by the other party, one wonders why a uniform redetermination provision makes sense. And what if a redetermination in 18 months results in a drastic reallocation of historic production numbers from the deemed majority holder to the minority holder? Are both parties equally placed to take the financial hits? The degree of complexity introduced by trying to unitise an already producing field with one that has not even been appraised requires a level of sophistication in designing preliminary frameworks that was wholly absent in the Minister’s proposed terms.

Ghana’s refusal to stick to these common global practices, egged on by the GNPC, was bound to lead all parties to the current impasse.

But why heap most of the blame on GNPC?

Much of the justification for blaming GNPC is best illustrated by its 24th May 2021 response to Eni’s assessment of Springfield’s Afina data. The tone of this rather shoddy piece of work was not merely cavalier and perfunctory, but also unanalytical.

Confronting the issue of why a well test has not been conducted at Afina, GNPC airily dismisses the point by citing “value for money”. In what world does testing a well in a field declared as suitable to be combined with another world for joint production not “value for money” when any data so collected would go to improve the eventual common reservoir model?

On the extremely critical issue of how much oil is in the Afina find, GNPC beat about the bush with speculations about possible differences in areas used in computation. No effort is made to actually address any discrepancy that could have resulted from such speculated geometric causes. They then quickly retreat to the ridiculous mantra that producing best estimates of oil in place is a “post-unitisation” matter. That is to say, the parties should just give up their rights on the say-so of the Minister and the calculations can come later.

Having been blatantly caught out for discrepancies in their use of inferences about the oil and water contact dynamics and compositions in the hydrocarbon column, GNPC barefacedly mumbles something about using data from other nearby structures to approximate the drivers of the volumetric figures. It is absolutely elementary in reservoir estimation to be confident about “fluid contacts” data. The dismissive approach GNPC took to this issue alone would absolutely have strongly reinforced perceptions of unprofessionalism and bias.

As a further sign of incompetence, GNPC does not include in any of its technical evaluations to the Minister the actual implication of unitization for Ghana’s own fiscal situation. As the crude nominal valuation analysis above shows, it is entirely possible for Ghana to lose money (due to the relative differences in participating interest in the pre-unitisation tracts) – maybe up to 25% – if Eni’s numbers turn out to be correct. In these circumstances, why would a National Oil Company breezily argue that sound estimation of commerciality is irrelevant in an assessment of unitization?

The only sound and professional thing for GNPC to have done when the Minister referred the matter for advice was to lay out the requisite preparatory work needed ahead of a pre-unitisation agreement. As the organization relied upon by the government for technical insight into the petroleum business, it was GNPC’s duty to know and to advise that a rush towards a Unit and Unit Operating Agreement was completely immature when the global best practice is to establish a preliminary framework within which issues of commerciality and optimal recovery can be thrashed out in an atmosphere of mutual trust and confidence.

By persistently pushing the thesis that all commercial determinations must happen “post-unitisation”, GNPC proves itself to be a wholly provincial, unsophisticated, and even oafish National Oil Company that cannot be relied upon to guide our political leaders to make right decisions for harnessing our national energy resource endowment.

The conduct of GNPC invokes comparison with that of Pemex, Mexico’s National Oil Company, which has led to a similar international dispute about the operatorship of the Zama field. A similar approach of disregarding international best practices has led to a Pemex that has been ranked as the world’s most indebted oil company, perpetually struggling to fund its capital expenditures.

It is clear that Ghana must follow the footsteps of Brazil and India and establish a technical agency for hydrocarbons (like Brazil’s ANP) that is focused on providing technical policy leadership in the petroleum sector (not merely exercising regulatory oversight like the Petroleum Commission) instead of one suffering from the schizophrenia of combining commercial hubris with technical policy savvy.

Of course, the culture and mandate of the Petroleum Commission can also be transformed for it to take over from the GNPC the role of providing technically sound, professional unbiased, purely national interest-driven, policy advice to the Government.

If this does not happen soon, GNPC’s reckless conduct will not only end up embarrassing the country, it will one day cost all of us billions of dollars we can ill afford.