Billionaire takes off for first ever private spacewalk

Billionaire Jared Isaacman has taken off in a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket for what he hopes will be the first ever privately funded spacewalk.

The mission, called Polaris Dawn, is the first of three funded by the founder of payments processing business Shift4.

He is onboard as commander alongside his close friend Scott ‘Kidd’ Poteet, who is a retired air force pilot, and two SpaceX engineers Anna Menon and Sarah Gillis.

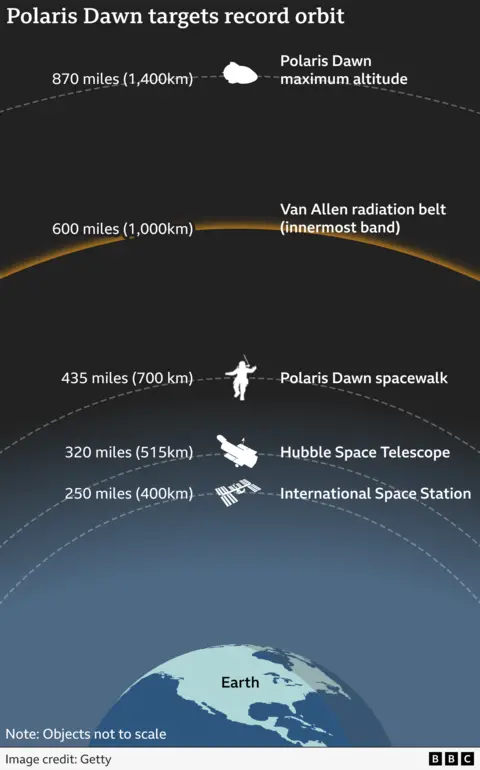

The spacecraft, called Resilience, will go into an orbit that will eventually take them up to 870 miles (1,400km) above the planet. No human has been that far since Nasa’s Apollo programme ended in the 1970s.

The astronauts will pass through a region of space known as the Van Allen belt, which has high levels of radiation, but the crew will be protected by the spacecraft and their newly upgraded spacesuits.

A few passes of the belt will expose them to the equivalent of three months of the radiation astronauts experience on the International Space Station, which is within acceptable limits. They aim to study the effects that a relatively short but safe exposure has on the human body.

The crew will spend their second day in space at their maximum altitude, conducting up to 40 experiments, including intersatellite laser communication between the Dragon Spacecraft and Space X’s Starlink satellite constellation.

If all goes to plan, on day three into the mission, Mr Isaacman and Sarah Gillis are expected to attempt the first ever privately funded spacewalk, which is scheduled to last two hours.

This will be while they are 700km in orbit. The astronauts will be testing new extravehicular activity (EVA) astronaut suits which, as their name suggests, have been upgraded from Space X’s intravehicular activity (IVA) suits for working outside of spacecraft.

The EVA suit incorporates a heads-up display in its helmet, which provides information about the suit while it is being used. The EVA suits are said to be comfortable and flexible enough to be worn during launch and landing, eliminating the need to have separate IVA suits.

In an interview given while she was training for the spacewalk Ms Gillis said that it was a necessary part of Space X’s plans to send people to other worlds.

“So far only countries have been able to perform a spacewalk. Space X has huge ambitions to get to Mars and make life multiplanetary. In order to get there, we need to start somewhere. And the first step is testing out the first iteration of the EVA spacesuit so that we can make spacewalks and future suit designs even better.”

It was a sentiment echoed by Mr Isaacman.

“Space X know they need EVA capability if they are going to realise their long-term dream of populating another planet someday.”

The aim is to make spacesuits less of a tailor-made garment, more able to accommodate a wider range of commercial astronaut shapes and sizes in order to reduce costs as human spaceflight becomes more commonplace.

Reuters

ReutersA unique aspect of the spacewalk is that the Dragon spacecraft, called Resilience, does not have an airlock, which is a sealed room between the doorway into the vacuum outside and the rest of the spacecraft.

Normally the airlock is depressurised before the astronauts step in and out, but in the case of Resilience, the entire craft will have to be depressurised and the non-spacewalking astronauts will have to be fully suited up.

The spacecraft has been adapted to withstand the vacuum. Extra nitrogen and oxygen tanks have been installed and all four astronauts will wear EVA suits, although only two will exit the spacecraft. The mission will therefore break the record for the most people in the vacuum of space at once.

The flight team has taken the challenge as an opportunity to do tests on the impact of decompression sickness, also known as the “bends” and the blurry vision astronauts can sometimes experience in space called spaceflight associated neuro-ocular syndrome.

Tests on the impact of radiation from the Van Allen belts as well as the spacewalk are intended to lay the ground for further high-altitude missions by the private sector possibly to the Moon or Mars.

SpaceX

SpaceXThere are an awful lot of firsts for the rookie crew to achieve. Isaacman has been in space only once before and the other three have never flown in space.

“There’s a feeling that there are a great many risks here,” according to Dr Adam Baker, a rocket propulsion specialist at Cranfield University.

“They have set themselves a lot of ambitious objectives and they have relatively limited spaceflight experience.”

“But in counter to that, they have spent several thousand hours simulating the mission. So, they are doing their best to mitigate the risks.”

If the mission is a success, some analysts believe that it will be the start of an explosion of ever greater and cheaper private sector missions taking more people further than government space agencies have.

But Dr Baker takes a more cautious approach.

“The record so far has been a huge amount of money spent by the private sector, lots of dribs and drabs of publicity, but much less than 100 additional people on top of the 500 or so government-funded astronauts travelling to space and back, and many of those only for very brief periods.

“Spaceflight is difficult, expensive and dangerous, so expecting to see large numbers of even just well-off members of the population, as opposed to the ultra-rich, flying into space soon, or expecting you might be among them, is unlikely.”

Reuters

ReutersSome find the idea of billionaires paying for themselves to go into space distasteful, and some eyebrows are being raised over a mission where the person paying for the trip is also the commander.

But this shouldn’t be brushed off as a vanity project, according to Dr Simeon Barber, a space scientist at the Open University, who develops scientific instruments on spacecrafts, almost entirely for government-funded projects.

“Isaacman is actually the most experienced astronaut of the crew – he alone has been to space before, on another self-funded mission with SpaceX, where he also took the position of Commander. In the context of the mission, he is the natural choice,” he told BBC News.

“More widely, the proceeds from selling this stellar class ticket to ride will remain on Earth – the money will buy materials and services, it will pay salaries and in turn will generate taxes. Not to mention the charitable funds the mission will raise.”

He says that many in the space sector believe the involvement of wealthy individuals to be a good thing.

“If they wish to venture off-planet, and one day to the Moon or even Mars, then that will create opportunities to do science along the way. And the more diverse the reasons there are to explore space, the more resilient the programme becomes.”