No speeches in front of cheering crowds. No joint public appearances between leaders. And a rumoured joint visit to a Germany-Turkey football match in Berlin that is not happening after all.

For a state visit, Friday’s visit by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to Germany is remarkably low key. He will meet German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier and then have dinner with the chancellor, Olaf Scholz.

Two meetings behind closed doors and a private dinner hardly speak of fanfare.

Apart from the intense security in the centre of the capital – the same level as precautions taken for US presidential visits — the German government hopes Mr Erdogan’s visit will pass with little notice.

That’s because this event couldn’t come at a worst time for Germany.

Relations between President Erdogan and successive German governments have been difficult for years, with spats between Berlin and Ankara regularly breaking out. When German government spokespeople mention the phrase “difficult partner” you know they’re talking about President Erdogan.

But the Hamas atrocities in Israel on 7 October, and Israel’s subsequent retaliation in Gaza, have left Germany and Turkey on opposite sides of the conflict.

Over the past month the Turkish president has become increasingly strident in his criticism of Israel.

He has refused to condemn the killings and hostage-taking by Hamas, referring to the group as “liberators”. Hamas is classed as a terrorist organisation by Western allies, including Germany.

He has also appeared to call into question the Jewish state’s existence by saying that Israel’s “own fascism” undermined its legitimacy.

Jewish leaders in Germany have accused Mr Erdogan of fuelling antisemitism with such comments and there have been calls for the German government to cancel the Turkish president’s visit.

For Germany, historical Nazi guilt for the Holocaust means that support for the state of Israel is non-negotiable and a key cornerstone of Berlin’s foreign policy. When asked in a news conference earlier this week about President Erdogan’s comments Chancellor Scholz called them “absurd”.

Both Olaf Scholz and former Chancellor Angela Merkel have repeatedly called Israel’s security Germany’s Staatsräson, or “reason of state”, a vague term German leaders use to express the idea of unwavering German support for Israel.

But as Israeli attacks on Gaza intensify, and the death toll rises, that principle is coming under strain.

After the initial shock of the Hamas attacks, German mainstream media is increasingly also portraying the humanitarian suffering in Gaza, leading to a growing unease about Israel’s actions.

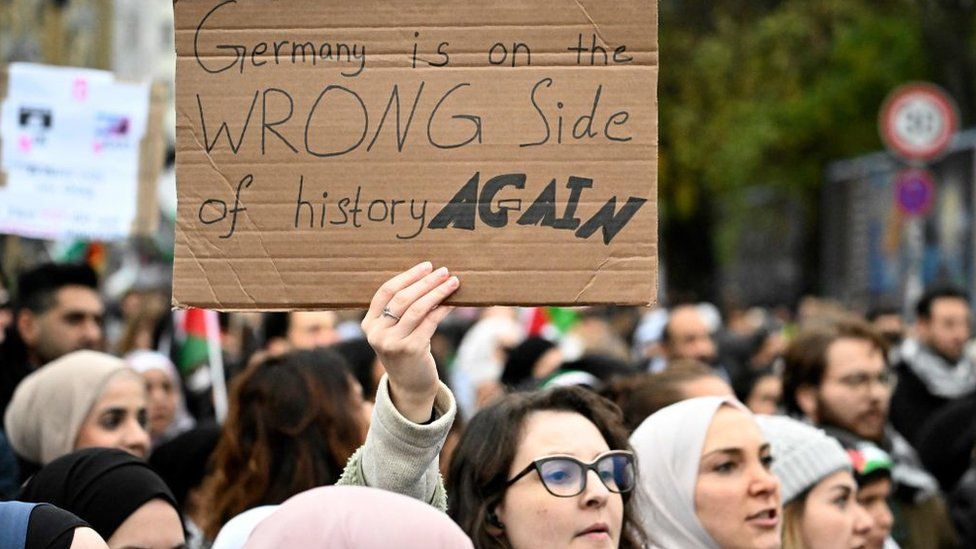

On German streets outrage at Israel’s actions is growing and pro-Palestinian demonstrations have been held most weekends since 7 October. Germany has large Arab diaspora communities with links to, or sympathy for, people in Gaza. Support for Palestinians is also traditionally a totemic issue for some German left-wing groups.

There are fears that any comments about the conflict by President Erdogan during his visit could inflame tensions.

But Germany and Turkey need each other. Germany is an important trade partner for Turkey. It also is home to the world’s largest Turkish diaspora community and is an electoral battleground for President Erdogan. He is popular with some German-Turks.

Around three million people of Turkish heritage live in Germany, with half of them still able to vote. In May a majority of Turkish voters in Germany who took part in the election put their cross by Mr Erdogan.

Berlin, meanwhile, needs Turkish help to control migration from the Middle East. Chancellor Scholz is hoping to revive a refugee pact with Turkey to send back asylum seekers and wants more Turkish support for the West in Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Behind closed doors on Friday those issues will be discussed. But the German government will be more nervous about what President Erdogan might say in public.

It was in May, after Mr Erdogan’s re-election as Turkish president, that Chancellor Scholz issued the invitation to Berlin. He probably now wishes he hadn’t.