Afghanistan: Ex-Bagram inmates recount stories of abuse, torture

Hajimumin Hamza walks through a long, dark corridor and carefully inspects the area as if he has never seen it before. Today, the 36-year old bearded man in a black turban and a traditional two-piece garment is a guide to fellow Taliban fighters in the place whose name he would rather forget. His eyes stop at a solitary chair standing on the pathway.

“They used to tie us to this chair, our hands and feet, and then applied electric shocks. Sometimes they used it for beatings, too,” Hamza says, recounting the torture he underwent during his captivity in Bagram prison between 2017 and the onset of the fall of Kabul last month, when he managed to escape.

The United States set up the Parwan Detention Facility, known as Bagram, or Afghanistan’s Guantanamo, in late 2001 to house armed fighters after the Taliban launched a rebellion following its removal from power in a military invasion.

The facility located within the Bagram airbase in the Parwan province was meant to be temporary. But it turned out otherwise. It housed more than 5,000 prisoners until its doors were forced open, days before the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan on August 15.

Sultan, who was jailed at Bagram between 2014 and August 2021, says he lost his teeth during what came to be known as enhanced interrogation techniques that rights groups say amounted to torture and violated international law. The 42 year old, who does not share his surname, opens his mouth to demonstrate the damage.

The Geneva Convention

The group of Taliban members passes a large plaque located at the prison’s wall with the words of the Geneva Convention in English and Dari but nobody cares to read it.

“The following acts are and shall remain prohibited at any time and in any place whatsoever (…). Violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture,” it reads.

But they all know that in Bagram, none of these rules applied. As the former prisoners say, if you entered Bagram, there was no way out. And if you were not an enemy fighter before landing there, you would surely leave as one.

None of the thousands of inmates who passed through the site over the 20 years of the American war, received the status of prisoner of war.

In 2002, after the death of two Afghan prisoners in detention, the centre came under scrutiny and seven American soldiers faced charges. The abuses, however, continued and soon became part of the “Bagram handbook”.

Hamza remembers much more than the electric shocks. Hanging upside down for hours. Water and tear gas being poured on sleeping prisoners from the bars on a cell’s ceiling. Confinement in tiny, windowless, solitary cells for weeks or months with either no light or a bright bulb switched on 24/7.

‘Black jail’

According to the former inmates, none of those who experienced solitary confinement, the so-called “black jail”, whose existence the US has denied, left the cells psychologically healthy.

“There were a lot of different forms of torture, including sexual abuse. They used devices to make us less of a man,” Hamza says, without giving details. “It is psychologically hard for me to recall all that was happening. The torture was mostly done by Afghans, sometimes the Americans. But the orders came from the US.”

Hamza joined the Taliban at the age of 16 following the US invasion. In his eyes, the Americans were invaders occupying his land. He saw fighting against them as his duty as a Muslim and Afghan. He would be given training in bomb and IED-making after his classes at the agriculture department at the Kabul University.

He was detained in summer 2017 and first transferred to Safariad prison in Kabul. He then was sent to two other detention facilities before ending up in Bagram four months later. As he says, he was tortured in all the jails he passed through. In the end, he was sentenced to 25 years.

“Eighty-five per cent of people in Bagram were Taliban, the rest were Daesh [ISIL, or ISIS] members. When the American and Afghan forces conducted their operations and couldn’t find any Talibs, they would capture innocent people. Some of them were kept here for years before they were released due to lack of evidence,” Hamza says.

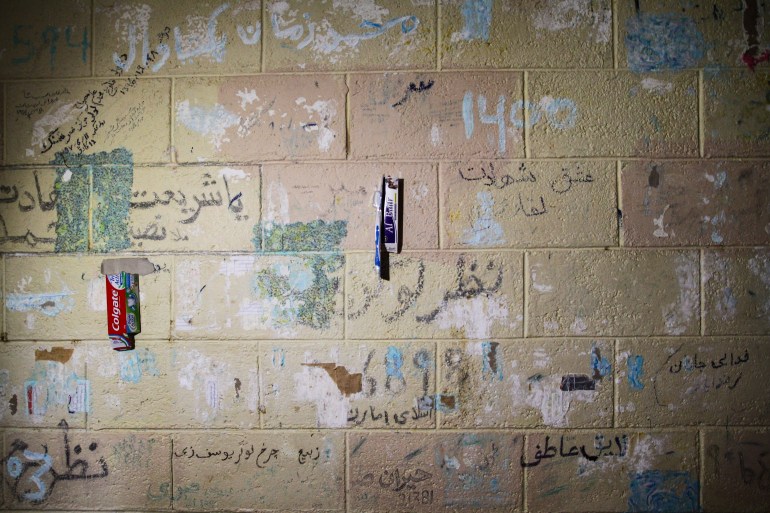

The former prisoners, along with a group of Talibs, walk through the cells in the prison’s barracks and take photos of what remains. Clothing, personal items and tea cups lie scattered on the floor. According to the prisoners, the cells had up to 34 inmates. The walls bear writings in Pashto and Dari.

“People were writing memories, like a diary. We did that because we wanted to leave a testimony in case the Americans kill us. So that people know that we were here,” Hamza says.

“In the beginning, we only had orange clothes but we protested against the colour and then were given white and black, more traditional garments. One piece of clothing per person. We had only one blanket each, even though it was cold in the winter months. Sometimes we had to share them with new prisoners. Some people waited months to get theirs.”

Prison rules

In front of a cell, a large plaque in Dari and English explains the prison rules.

Rule 1: NO THROWING. No throwing or assaulting guards with any object or liquids. You will not throw anything at my guards.

Rule 3: NO SPITTING. You will not spit on my guards or other detainees.

Rule 7: NO DISOBEDIENCE. You will follow all orders of the guard force. There are no exceptions.

But the rules were not always followed.

“I bought a phone from a guard for 1,000 Afghanis ($11.50), we found a hole in the wall and when we had a connection, we made phone calls,” Hamza says. “I had it for two years. It was found a few times, but I always managed to get another one.”

It was the phone that eventually helped the prisoners escape. As the US forces left the base on June 2 without informing the Afghan government and the Taliban intensified its military offensive, Bagram was left with little supervision.

“One of us felt sick and we were calling for help. But no one came. There was only silence,” Hamza says. “This was when we decided to run away. We broke the bars with the metal plates our food was served on.”

A Taliban fighter inspects solitary confinement booths in the ‘black jail’ [Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska/Al Jazeera]

A Taliban fighter inspects solitary confinement booths in the ‘black jail’ [Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska/Al Jazeera]After getting out of their cells, the inmates took the weapons left behind by the US Army and captured the few Afghan guards who were still left. They eventually freed them, as well as other inmates.

“More than 5,000 prisoners escaped but I’m not sure how many. The corridors were full of people. I took my phone, found a place to charge it and made a phone call,” says Hamza.

Shortly afterwards, his brother came to pick him up. But the reality outside was unfamiliar.

“When we went out we couldn’t recognise anything, especially the kids. We spent a lot of time with adults only, we hadn’t seen our families. People, cars, everything seemed foreign,” Hamza says.

‘We are not like the Americans’

It is the first time that Hamza has returned to the prison after fleeing. A prison that he never thought he would leave. He walks through the grounds of the former US airbase, where personal items of soldiers and prisoners, food and elements of armour, lie in a disordered mess and he says he is happy that he is now free.

He does not specify what happened to the Daesh fighters who served time along with the Taliban.

About 65 kilometres south at Pul-e-Charkhi prison in Kabul, Mullah Nooruddin Turabi sits on a chair in a prison office. The Taliban leader has been recently appointed as the head of Afghanistan’s prison system, the same function he had under the previous Taliban government in the 1990s. He returned to Afghanistan after 20 years of exile in Pakistan, where many Taliban officials took refugee status following the US invasion.

“Our deeds will show that we are not like the Americans who say that they stand for human rights but committed terrible crimes. There will be no more torture and no more hunger,” Turabi says, as he explains that the new prison staff will include members of the old system and the Taliban mujahideen.

“We have a constitution but we will introduce changes to it and, based on those changes, we will revise the civil and criminal codes and the rules for civilians. There will be much less prisoners because we will follow the rules of Islam, humane rules.”

Turabi does not comment on the killing of four people during the protest in Kabul on September 10, or mounting evidence of the torture against journalists and civilians still being carried out in prisons.

When asked whether the new justice system will mirror the previous Taliban order, he answers with little hesitation.

“People worry about some of our rules, for example cutting hands. But this is public demand. If you cut off a hand of a person, he will not commit the same crime again. People are now corrupt, extorting money from others, taking bribes,” he says.

“We will bring peace and stability. Once we introduce our rules, no one will dare to break them.”