On the morning of March 13, Faustina Tay sent a final desperate message to an activist group she had contacted about the abuse she was suffering at the hands of her Lebanese employers.

“God please help me,” the 23-year-old Ghanaian domestic worker wrote.

About 18 hours later, she was found dead.

Tay’s body was discovered in a car park under her employers’ fourth-storey home in Beirut’s southern suburbs, between 3 and 4am on March 14.

A forensic doctor who examined her body found that her death was caused by a head injury “as a result of falling from a high place and crashing into a solid body”.

The doctor found “no marks of physical assault”. A search of Tay’s employers’ home found no signs of a struggle, and the death was being investigated as a suicide, according to a police report.

Hussein Dia, whose home Tay had lived and worked in for 10 months at the time of her death, told Al Jazeera he and his family had been sleeping when she died.

Dia said he did not know what had driven the 23-year-old to take her own life, and denied he ever physically assaulted her – “I never laid a hand on her.”

But in the week before her death, Tay sent dozens of texts and more than 40 minutes of voice messages to Canada-based activist group, This Is Lebanon, and her brother in Ghana, providing detailed accounts of recurrent physical abuse.

This Is Lebanon names and shames employers accused of maid abuse online in an attempt to resolve issues facing domestic workers on a case-by-case basis.

Human Rights Watch found in a 2010 report that Lebanon’s judiciary fails to hold employers accountable for abuses, while security agencies often do not “adequately investigate claims of violence or abuse”.

Tay told the group that Dia and Ali Kamal, the owner of the domestic worker’s agency that had brought her to Lebanon, had each beaten her twice between January 16 and March 6.

Kamal had beaten her along with one of his employees, Hussein, she said.

In the messages, Tay repeatedly expressed concerns that speaking about her ordeal could lead to more abuse, and the confiscation of her phone, which she said had taken place once before.

She also feared much worse.

“I’m scared. I’m scared; they might kill me,” she said, in a chilling voice note to activists.

‘Modern-day slavery’

The manner of Tay’s death is not uncommon in Lebanon, a country with about 250,000 domestic workers. Two die each week, according to the country’s General Security intelligence agency, with many falling from high buildings during botched escape attempts, or in cases that are ruled suicides.

Domestic workers like Tay are employed under the country’s notorious kafala system, which ties their legal residence to their employer, making it very difficult for them to end their contracts.

This sponsorship system, which is in place in several Middle Eastern countries, has facilitated a range of abuse, such as non-payment of wages, a lack of rest time and days off, and physical and sexual assault.

Lebanon’s former Labour Minister Camille Abousleiman likened the system to “modern-day slavery,” and began a process of reform that is still in its early stages.

Women who come to Lebanon for domestic work from a host of Southeast Asian and African countries such as the Philippines, Nepal and Ethiopia are usually looking to support their families back home and eventually return.

Tay’s case sheds light on the type of abuse that ends with many returning to their families in coffins.

From Accra to Beirut

A little more than 10 months before her death, Tay had been running a small noodle business in Ghana’s capital Accra, with financial help from her brother Joshua Demanya, who works as a driver.

Demanya told Al Jazeera that he had advised his sister against going to Lebanon “because there have been stories of people who go there and suffer so much they run away”.

Photo: Faustina Tay, pictured here on her way to Lebanon, was found dead on March 14 in southern Beirut [Courtesy of Demanya family]

Tay ignored her brother’s advice and arrived in Beirut on May 5 to begin working at Dia’s apartment, where he lives with his wife, Mona, and their three children.

There, she did not have her own room, instead, she slept on a sofa in the kitchen. She complained that she was overworked, had no days off and was usually only able to get to sleep at 2am and was woken up at 8am.

Beirut, Lebanon – On the morning of March 13, Faustina Tay sent a final desperate message to an activist group she had contacted about the abuse she was suffering at the hands of her Lebanese employers.

“God please help me,” the 23-year-old Ghanaian domestic worker wrote.

About 18 hours later, she was found dead.

Tay’s body was discovered in a car park under her employers’ fourth-storey home in Beirut’s southern suburbs, between 3 and 4am on March 14.

A forensic doctor who examined her body found that her death was caused by a head injury “as a result of falling from a high place and crashing into a solid body”.

The doctor found “no marks of physical assault”. A search of Tay’s employers’ home found no signs of a struggle, and the death was being investigated as a suicide, according to a police report.

Hussein Dia, whose home Tay had lived and worked in for 10 months at the time of her death, told Al Jazeera he and his family had been sleeping when she died.

Dia said he did not know what had driven the 23-year-old to take her own life, and denied he ever physically assaulted her – “I never laid a hand on her.”

But in the week before her death, Tay sent dozens of texts and more than 40 minutes of voice messages to Canada-based activist group, This Is Lebanon, and her brother in Ghana, providing detailed accounts of recurrent physical abuse.

This Is Lebanon names and shames employers accused of maid abuse online in an attempt to resolve issues facing domestic workers on a case-by-case basis.

Human Rights Watch found in a 2010 report that Lebanon’s judiciary fails to hold employers accountable for abuses, while security agencies often do not “adequately investigate claims of violence or abuse”.

Tay told the group that Dia and Ali Kamal, the owner of the domestic worker’s agency that had brought her to Lebanon, had each beaten her twice between January 16 and March 6.

Kamal had beaten her along with one of his employees, Hussein, she said.

In the messages, Tay repeatedly expressed concerns that speaking about her ordeal could lead to more abuse, and the confiscation of her phone, which she said had taken place once before.

She also feared much worse.

“I’m scared. I’m scared; they might kill me,” she said, in a chilling voice note to activists.

‘Modern-day slavery’

The manner of Tay’s death is not uncommon in Lebanon, a country with about 250,000 domestic workers. Two die each week, according to the country’s General Security intelligence agency, with many falling from high buildings during botched escape attempts, or in cases that are ruled suicides.

Domestic workers like Tay are employed under the country’s notorious kafala system, which ties their legal residence to their employer, making it very difficult for them to end their contracts.

This sponsorship system, which is in place in several Middle Eastern countries, has facilitated a range of abuse, such as non-payment of wages, a lack of rest time and days off, and physical and sexual assault.

Lebanon’s former Labour Minister Camille Abousleiman likened the system to “modern-day slavery,” and began a process of reform that is still in its early stages.

Women who come to Lebanon for domestic work from a host of Southeast Asian and African countries such as the Philippines, Nepal and Ethiopia are usually looking to support their families back home and eventually return.

Tay’s case sheds light on the type of abuse that ends with many returning to their families in coffins.

From Accra to Beirut

A little more than 10 months before her death, Tay had been running a small noodle business in Ghana’s capital Accra, with financial help from her brother Joshua Demanya, who works as a driver.

Demanya told Al Jazeera that he had advised his sister against going to Lebanon “because there have been stories of people who go there and suffer so much they run away”.

Tay ignored her brother’s advice and arrived in Beirut on May 5 to begin working at Dia’s apartment, where he lives with his wife, Mona, and their three children.

There, she did not have her own room, instead, she slept on a sofa in the kitchen. She complained that she was overworked, had no days off and was usually only able to get to sleep at 2am and was woken up at 8am.

‘I should have stayed’

She quickly regretted her decision to leave Ghana. In November 2019, she texted her brother: “I should have stayed [and] continued with my business.”

In January, she told her employers that she could not work for them any more, and asked to be sent back home. They refused – “I paid $2,000, and I said, ‘Take it easy on us, we’ll let you travel after Ramadan,'” Dia recalled telling her.

That was when Tay said Dia beat her for the first time, on January 16, before taking her to Kamal’s agency, where she said Kamal and Hussein beat her.

Both denied the claims when contacted by Al Jazeera. Kamal said his agency, established in 1992, brings roughly 1,000 domestic workers into Lebanon every year. “The state would have closed us a long time ago,” if they mistreated domestic workers, he said.

Kamal informed Tay that the only way she would get back home was if she worked two more months with the Dia family, to pay for her ticket back to Ghana.

She agreed.

But when the agreement came due in March, she contacted This Is Lebanon and said Dia was refusing to let her leave. A few days later, on March 10, she said Dia, Kamal and Hussein beat her again.

“My boss beat me mercilessly yesterday [and] dis (sic) morning he took me to the office [and] I was beaten again, this is the second time they beat me up in the office.”

Dia said he had taken Tay to the agency with the intent of letting her travel, but received a call two hours later from the agency: “We’ve worked it out, she’ll travel in July.”

Demanya said his sister had agreed “out of fear”.

‘I don’t want to die here’

Al Jazeera informed Lebanon’s Labour Ministry of Tay’s case. An adviser to Labour Minister Lamia Yammine said that the names of Tay’s employers had been noted and the ministry would be informed if they applied to be allowed to employ another domestic worker.

She said they would be permanently blacklisted “if it is proven later on that the suicide was caused by abuse”.

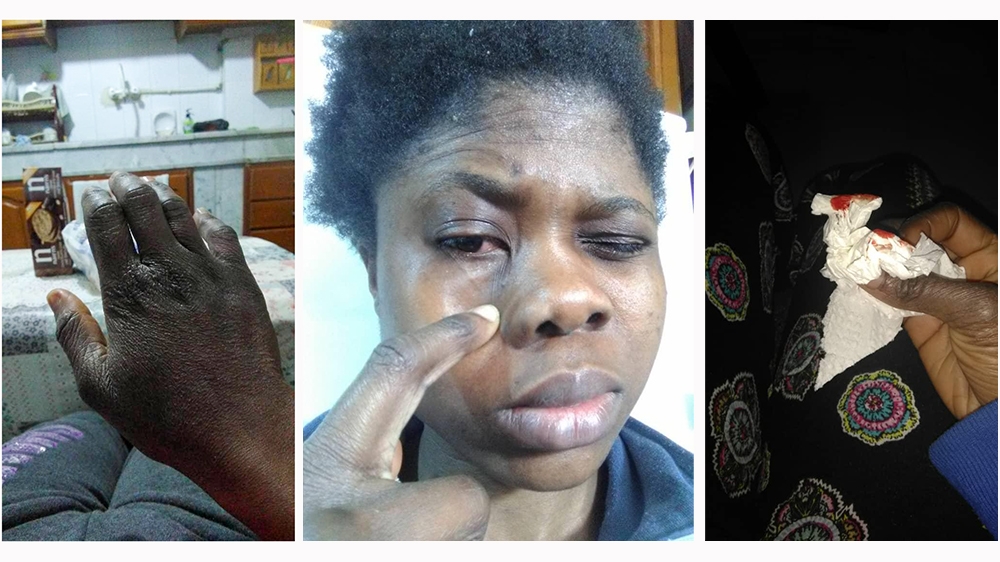

On March 12, Tay sent a series of pictures to her brother, appearing to show an inflamed hand, a bruise on her forearm and a scratch underneath her eye that she said were caused by the beatings.

She also shared a picture of a bloody tissue that she said was the result of a nosebleed.

Despite the abuse, she described, Tay expressed a strong will to live.

“I’m very, very weak,” she said in a voice message, describing pain in her wrist, legs and neck.

“Please, help me. Help me to go back to my country for treatment. Please, I don’t want to die here.”