Adoley (not her real name) and her sister had no idea how unbearable their one-year stay would be when they moved into their new home at Adenta New Site.

It was a two-bedroom apartment for which the landlord demanded that they pay a one-year advance of GHS 14,440 or risk losing their room to another potential tenant. That meant, every month, GHS 1,200 of their earnings went into the landlord’s pocket as rent.

Apart from paying GHS 14,400 cedis upfront, they were required to pay a security deposit of 1,200 cedis a year. The money, according to the landlord, was allocated to cover maintenance, renovation, and other potential costs associated with their new accommodation.

The same landlord who didn’t have to make any payments to Ghana Water Company for water also insisted that the tenants pay 350 cedis for water he provided from a well.

Living in the apartment was hell for them. It was always, according to her, “from one issue to the other”.

Per the tenancy history of the apartment, no tenant had lived there for more than a year. After a year, they either left because of the landlord whose discretion and decisions make living harder than the economic hardship or they left to keep their sanity intact.

Adoley is not alone in this. Many Ghanaians experience similar difficulties when they secure a place to stay. Sometimes, the discomfort and challenges with renting start even before moving into the residence.

Housing deficit in Ghana

Rent issues, which are only a fragment of a housing deficit, are an alarming socio-economic issue in Ghana.

Per the 2021 Population and Housing Census released by the Ghana Statistical Service, over 10 million (10,661,421) structures were listed.

The Ghana Statistical Service explains that housing deficit has reduced by 33% (1.8 million units) for the first time. Though a reduction sounds good to know, like our teachers’ remarks, there is always “more room for improvement”. The 33% makes little meaning to ordinary Ghanaians as it doesn’t translate into affordability of houses.

For a country whose total population is 30,792,608, the housing deficit of 1.8 million has made the cost of rent unbearable and regulation difficult. Places of residence are largely owned by individuals who determine their own rent and payment plan.

House Rent in Ghana

Abraham Maslow’s Theory of Needs shows that man’s psychological needs, including shelter, ought to be satisfied first before others are considered. Thus, if a person’s psychological needs are not fulfilled, one cannot function optimally.

If functioning optimally is anything to go by in this country, then one wonders the number of people who are malfunctioning due to the rent and housing challenges.

Rent in Ghana can be overwhelmingly outrageous. Many people, young and old, are struggling with exorbitant rent that inevitably rises with or without a good reason.

In Accra, specifically, finding a good place of residence is one thing, and finding an affordable place devoid of landlord-tenant drama is an exception to the rule. And when you find yourself in a position of not paying rent, you can only count yourself as part of the lucky ones.

That is why when I came across Anna-Liza Afiba Arthur’s comment on Facebook, though not surprising, I still find it worrying that rent is a headache we haven’t found a cure for. She wrote: “My plight, a single mom of 3, paying 800 a month and now landlord increase to 1,400. I can’t pay so he asked us to move out bcos [sic] someone has taken it. Hmm, I’m even looking for a place to perch and gather money to rent. Rent in Accra is crazy.”

For many people, rent has dug a hole in their pockets, draining their finances faster than their other needs.

Source: Tell it All, Facebook page

In addition to the existing challenges with rent, there are the middlemen, or agents, as they are popularly called. The have also grabbed the opportunity to make money from prospective tenants.

Not only are they making more money, but some of them are also creating more hardship for people as they fleece prospective tenants. These unregulated housing agents operate by their own terms and conditions.

The Landlord, the Tenants and the Law

I cannot even count the number of people whose experiences with landlords and tenants I have heard, witnessed or read about—the unfortunate ones, the dramatic and sad ones, the legitimate issues and the irrelevant ones.

Enam is one of such whose story I can’t forget. She and her husband only lived in their apartment at Odorkor for three years.

Like Adoley, they sang the same song: “It was always from one issue to the other” except that they had to frequent the Rent Control Department with their landlord to settle their “matter” which was no matter at all. It wasn’t anything that could be weighed or deserved to take up space in Rent Office.

They only asked for an extension in a letter to stay in his apartment three months ahead of their ejection date. The rent law makes provisions for this arrangement.

But the landlord’s response, which came in a letter, directed them to Rent Control Department to explain why they didn’t want to move out. The rest of the story was only a cocktail of drama and constant visits to the Rent Office. Eventually, they moved out after combing Accra for several days for a place.

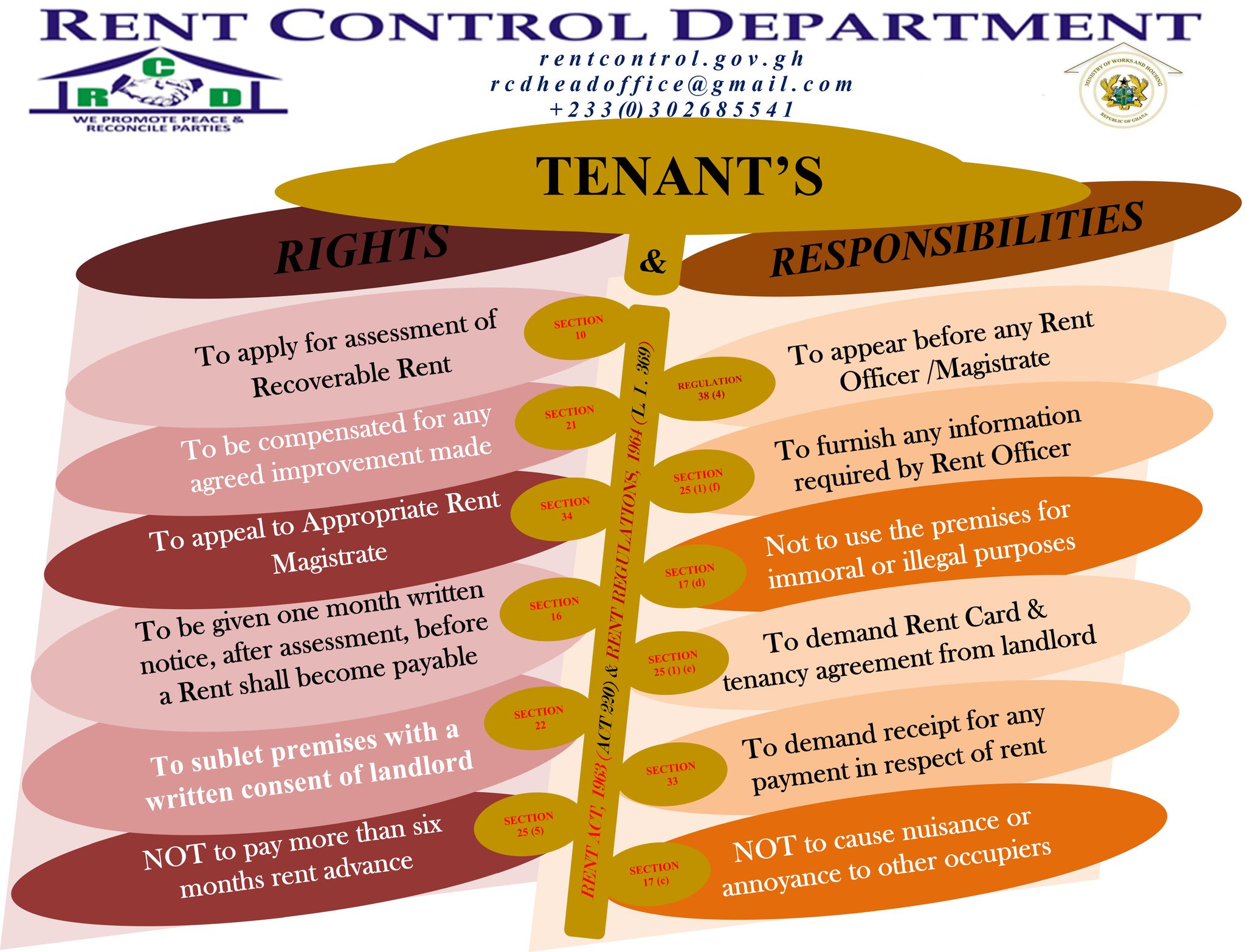

The Rent Law 1963 (Act 220) regulates the rent market in Ghana. Per the law, it is an offence for any landlord to take more than six months’ advance rent for places of residence.

While the Rent Law frowns on such acts, neither the landlords nor their caretakers frown on it. In elation, they receive their “unlawful” advance rent payment.

This law has remained law in the archives of the lawmakers while the reality is on the ground. The power of the landlords is only as strong as the system allows them, making them somehow, more powerful than the law.

What has been said and done?

Since the colonial era, several attempts including policies and initiatives have been made by successive governments to address the housing gap in the country.

During the 2020 general elections, both the New Patriotic Party (NPP) and the National Democratic Congress (NDC) promised to address the challenge of the housing deficit.

The NPP promised to establish “a National Rental Assistance Scheme (NRAS) which will provide low-interest loans to eligible Ghanaians to enable them to pay rent in advance. These loans will be repaid on a monthly basis to match the tenor of the rent and will be insured to ensure sustainability. The government will seed the Scheme with GH¢100 million which will be leveraged to crowd in additional investment from the private sector.”

The NDC said it wanted to “engage landlords, real estate investors and tenants to review the Rent Act to provide tax incentives to landlords and real estate investors to reduce the cost of rent advance for residential and commercial purposes.”

Ghanaians want every government to address issues that affect our living standards, including radical measures on rent issues.

That is why I concur with the Minister for Works and Housing, Francis Asenso-Boakye’s, comments in a recent publication by the Daily Graphic that “over the years, one of the reasons our public housing programmes have lagged behind and failed is that we don’t have an implementing agency whose responsibility is to manage housing developments in Ghana”.

Cabinet is said to have approved a policy that will ensure the formation of the Ghana Housing Authority (GHA) to execute the public housing programmes, but I’m not confident it will yield anything meaningful.

The NPP also promised to “implement the necessary regulatory, institutional, and operational reforms of the Rent Control Department, including the digitisation of their operations”. As of November 2022, we are yet to see that digitisation take effect.

I do not believe that governments treat housing and rental issues with any seriousness when they have the power to do.

What I foresee in the coming years is a dire situation of lawlessness and abuse of power by the few who have the resources to control the rent market while abandoned government housing projects continue to waste away.

The Way Forward

Over the years, urbanisation, migration, and population growth have significantly contributed to the high demand for housing, a situation that can become dire if we fail to address it holistically.

Government and investors must create more affordable housing projects whose affordability will not only be in name but also correspond with the pockets of the people of Ghana.

More houses are needed to bridge the demand and supply gap. This cannot be the responsibility of individuals alone. I believe the challenge in the housing sector is such that a national scheme to provide loans to tenants may be inadequate to tackle the challenges we are grappling with. The government’s active involvement in the ownership of homes is a sure way to control the challenge.

The Rent Law 1963 (Act 220) is outdated and inadequate to meet the demands and mishaps of our times. The Rent Laws should be reviewed immediately, and I am learning a new Rent Control Act has been drafted for review by Cabinet in this direction. This is even long overdue and must not be delayed any longer.