‘I hugged the man who murdered my father’

When Candice Mama was nine years old, she secretly opened a page in a book she wasn’t meant to look at. The picture she saw there revealed something terrible – the dead body of her murdered father. But years later Candice went on to meet and forgive the killer – a man known as “Prime Evil”, Eugene de Kock.

“Where did the girl go from Soweto, where did the girl go from Soweto…”

Whenever The Girl from Soweto by Clarence Carter plays on the radio, 29-year-old Candice Mama smiles – she knows this was one of her father’s favourite songs.

Yet she never got to see him sing or dance along to it.

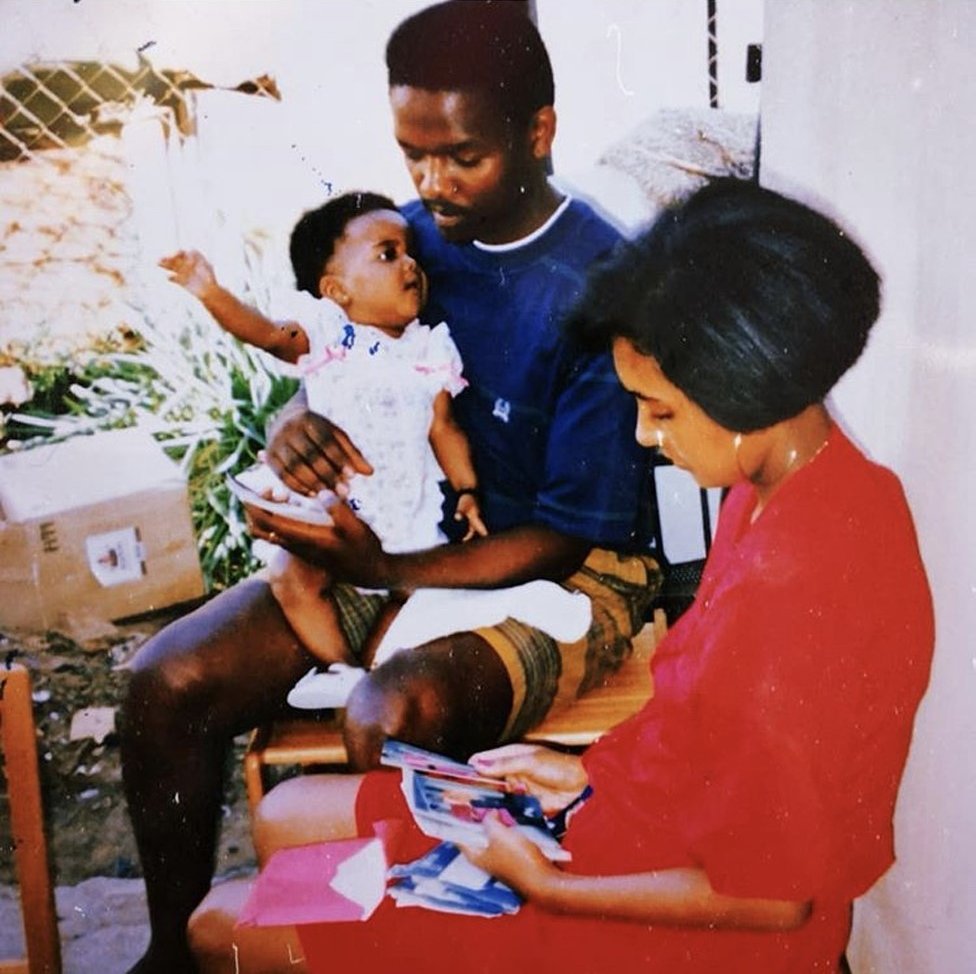

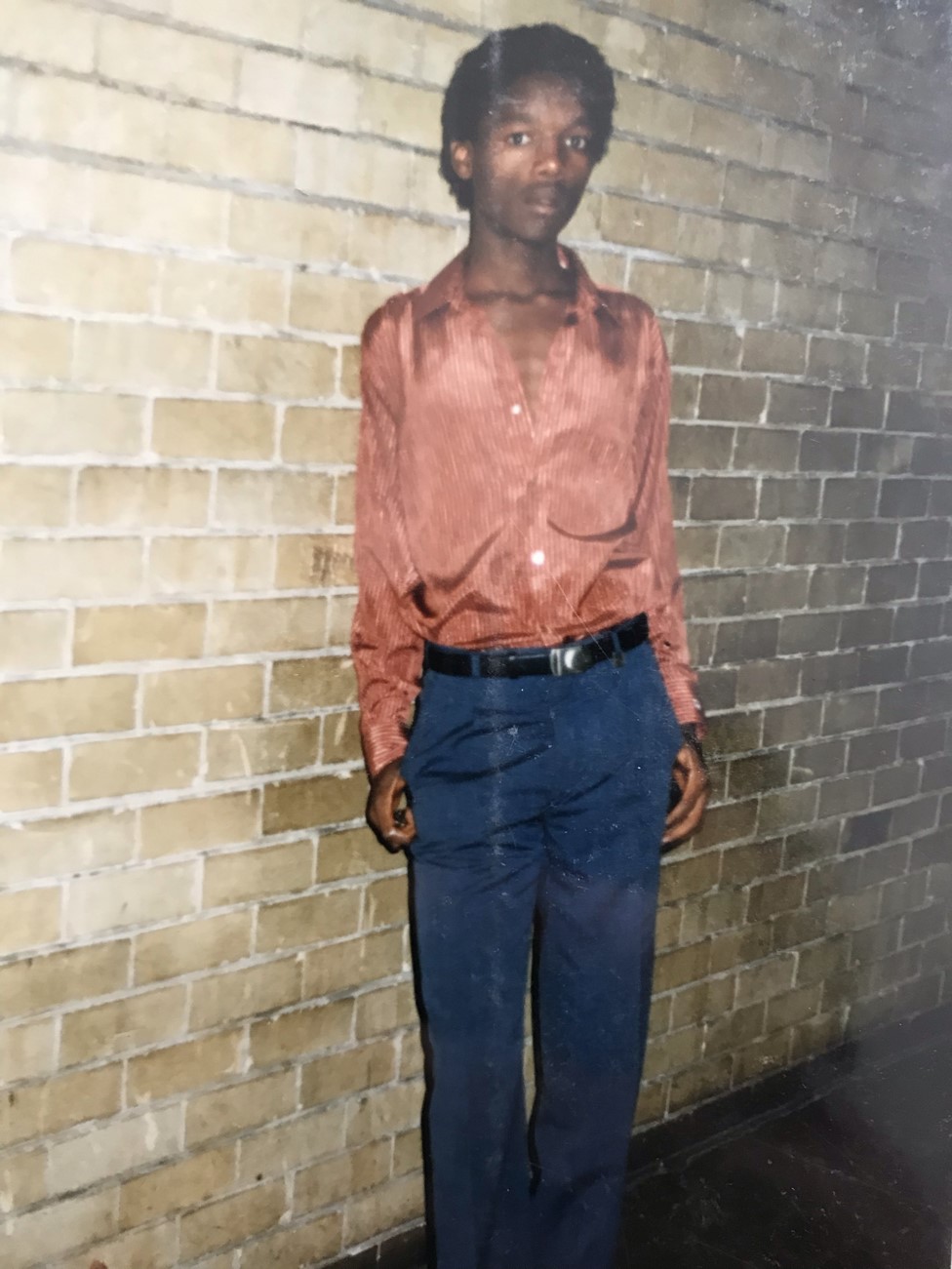

Glenack Masilo Mama died when Candice was just eight months old, so she spent her childhood piecing together an image of him from other people’s memories.

“He was someone who really loved life,” says Candice. “He was someone who was so just in the moment. If he heard a good song, no matter where he was, he was going to jump up and dance.

“Candice was born in South Africa in 1991, as the apartheid system – enforcing strict segregation of races – was slowly being dismantled.

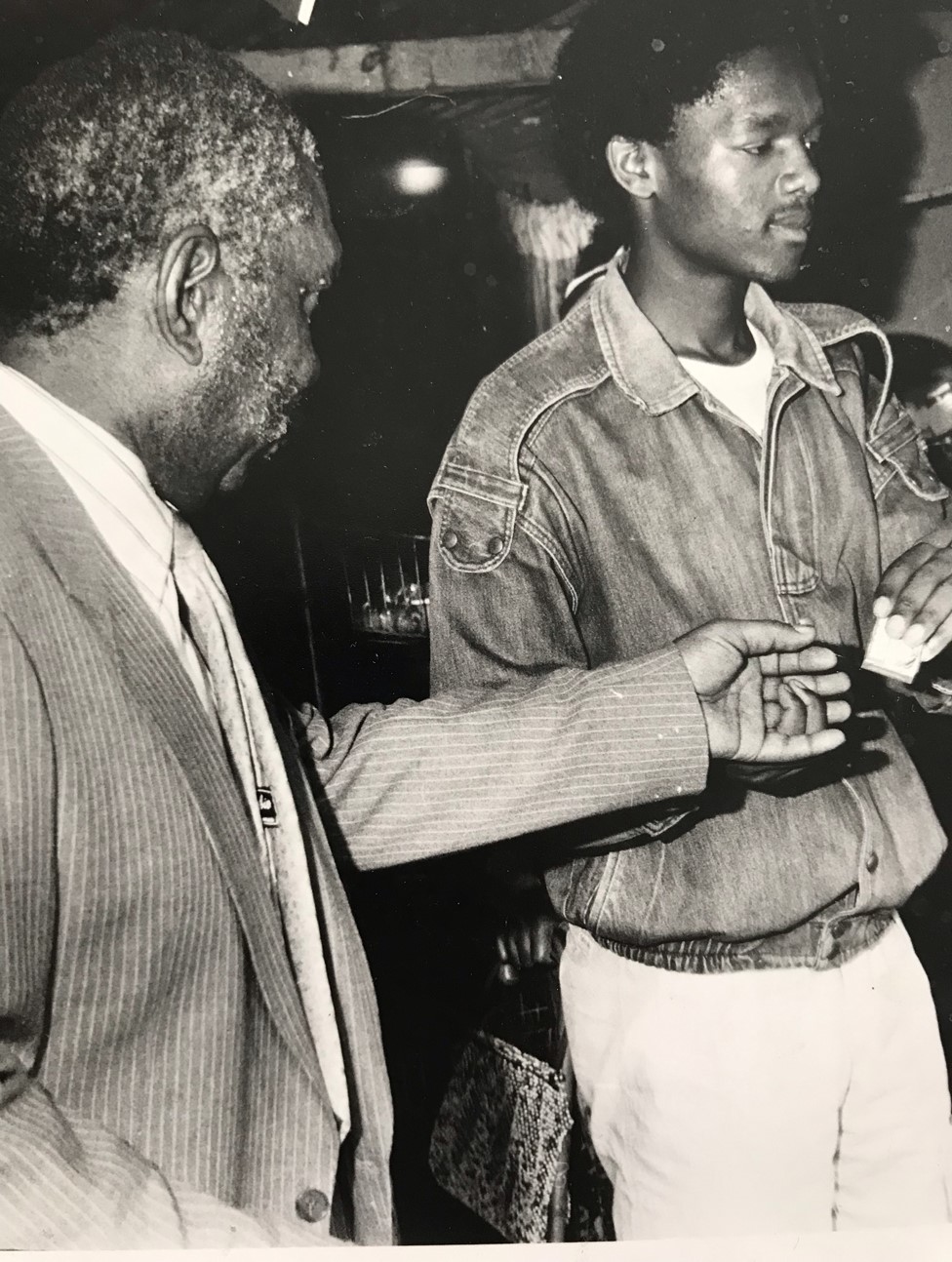

Her mother, Sandra, was mixed race. Glenack, her father, was black, and a member of the Pan Africanist Congress – a group struggling against apartheid alongside the African National Congress (ANC), but opposed to the ANC’s principle of equal rights for all nationalities in South Africa.

Candice always knew that her father had been murdered. She even knew the name of the murderer – Eugene de Kock, the notorious commander of the Vlakplaas police unit, a squad responsible for the torture and murder of black anti-apartheid activists. But her mother had spared her the horrifying details.

It was at the age of nine that she found out some of these details herself, after noticing that a book called Into the Heart of Darkness – Confessions of Apartheid’s Assassins – had a powerful effect on her mother’s visitors.

“Every time people would come over to the house she would ask me to go get this book, and people would cry and I’d hear screaming,” Candice says. “I’d hear all these odd reactions, or at least what I considered odd at the time, and I just thought to myself, ‘I know my dad is in this book, but I want to know, why is he inciting these reactions?'”

One day she overheard the page that they turned to.

“So I told myself, ‘OK, when I get the opportunity I’m going to turn to this page and just see.'”

About a week later, when her mother went shopping, Candice climbed on a chair and reached up high to take the book from the top of a cupboard in her mother’s bedroom.

She opened it to the page she had heard mentioned, and saw the horrific picture of a burnt body – her father – clutching the steering wheel of a car.

“In my mind, immediately I connected the fact that this was my father, this was how he died and he [Eugene de Kock] is the person who did it. And because I knew what I did was wrong, that I wasn’t allowed to open that book, I held it within myself.”

Not saying anything to her mother, Candice says the resentment within her began to “grow and become something else”. But her desire to find out more about her father only increased.

“I found a picture album of his,” says Candice. “I saw his pictures and his personality and quotes that he would just stick into this book. He just seemed so enlightened, especially for someone living in the situation he was living in.

“One thing he said was, ‘Just because you’re black doesn’t mean that you can’t get ahead in life.’ I always find it so fascinating, realising that this man at 25 had all this knowledge within himself, and I would have wanted to see what became of him.”

But the pain and anger Candice was bottling up inside herself eventually began to affect her health.

One night, at the age of 16, she was rushed to hospital with a pain in her chest so severe it was feared she was having a heart attack.

“The following day the doctor sat myself and my mum down and he said, ‘You know you weren’t having a heart attack, but in my over 20-something years of experience, I have never seen stress symptoms so severe in someone your age,'” Candice says.

“He started pointing at all these different things that were manifesting in my body, all these ulcers, all these symptoms, and he said, ‘I don’t know how to tell you this, but your body’s killing you, and if you don’t change something I think you’re really going to pass on.'”

Candice acknowledged there was a problem. “I was not happy, healthy or even living to be honest,” she says.

She began to look for ways to heal herself, and traced the problem back to the photograph that had revealed to her what happened to her father. She had to confront it and make it less toxic, she reasoned, and she began by finding out more about her father’s killer.

In 1995, the year after South Africa’s first democratic election – which brought the ANC and its leader, Nelson Mandela, to power – a Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established, to hear the testimony of those who had committed human rights violations under apartheid. All the transcripts were put online for posterity, so Candice was able to type in the name Eugene de Kock and read any document in which it appeared.

In one, called the Nelspruit Amnesty hearing, de Kock talked in detail about the events of the day Candice’s father was murdered. On discovering the document, she felt “a pit building in my stomach”, she writes in a published memoir. As she read she shuddered with anger, she says – she couldn’t understand how a man could act in this way.

Before long, she concluded that she needed to do what for some would be the unthinkable – she had to forgive the man who had taken her father away from her.

“It started as a revenge in some ways, because I thought to myself, ‘Every time I think of this man it’s like he controls me, I get these panic attacks. It’s like I’m not in control of my own emotions.’ I was like: ‘No, he already killed my father and now he’s killing me too.’ So for me, forgiveness wasn’t so much something I could just think about doing, it was something that was crucial for me.”

She was still a teenager, but she took control of her emotions.

“When I decided to remove the emotional attachment that I held towards Eugene and the incident that had occurred, I started realising that, ‘OK, I am forgiving this person.’ And that’s what forgiveness became to me, not having an emotional response to that trauma.”

She found this hugely liberating.

“I was just like, ‘Whoa I can feel light, I can feel joy, I can be happy.’ Those were things that I’d never even entertained at some point and the irony is, until I got to a point where I forgave Eugene, I actually didn’t think I needed those things.”

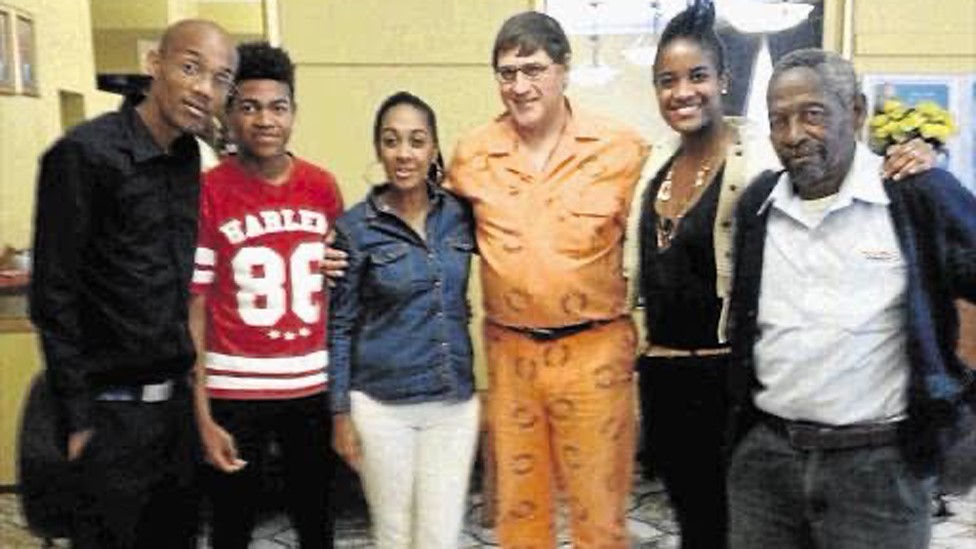

In 2014, Candice’s mother was contacted by the National Prosecuting Authority to ask if the family would like to take part in a victim-perpetrator dialogue and meet Eugene de Kock face to face.

Candice was 23 at the time, and when her mother asked if it was something they should do she replied instantly.

“I said yes, and I don’t know why,” she says. “I knew instinctively that if I didn’t say yes it was going to be something I would question for the rest of my life.”

The experience of entering the room where the meeting was to take place was surreal, says Candice.

“You go in and it’s like this long dining room table that’s been set up, and there’s scones in the corner and there’s biscuits – you know, like if you’re going to your aunt in the township.”

The family began talking to the prison guards, the prison counsellor and a priest, but at a certain point Candice turned round – “and I just saw him, I just saw him sitting there, like he had appeared from thin air.”

Two things shocked her.

“He looked like he’d been frozen in time. From the pictures I’d seen as a child to who was sitting there was the exact replica of the same person, it was unreal,” Candice says.

But also, she had expected this 65-year-old man, the man known as Prime Evil, to have an aura – an evil aura. And she was surprised to find that he didn’t.

As the priest introduced the family one by one, Eugene de Kock would lean forward and say: “Pleasure to meet you.”

Candice’s mother began by asking what had actually happened to her husband on 26 March 1992 – the day he died.

Eugene told them that he and his team had sent an infiltrator into her father’s camp to identify the most radical and skilled activists – the most “dangerous people” within the Pan Africanist Congress – says Candice. Her father and three other men were chosen.

On that day, he was due to drive to Nelspruit, a city 350km east of Johannesburg (renamed Mbombela in 2014).

“What he didn’t know was that Eugene De Kock and his team had set up an ambush,” says Candice.

“So as my dad was driving under the [Nelspruit] bridge, the team started firing at the minibus.

“When Eugene de Kock, from the bridge, realised that the car wasn’t coming to a stop, he ran down the embankment and he emptied out his magazine cartridge on my father, and when he still saw signs of life in the vehicle, he doused them all in fuel and he set them alight.”

We tell ourselves that normal human beings are not capable of such atrocities, Candice says. But at this moment, it seemed very clear to Candice that Eugene de Kock was a normal human being, albeit one who did some “extraordinarily terrible things”.

“It almost forces you to step into their shoes for a little bit and say, ‘You know what, if I had been dealt this pair of cards, if I had been raised by a militant father in a militant family, went to police academy, lived in an environment that told me that this was the enemy and this is what’s right, and then I went on to be celebrated by my friends, by my peer groups for being the best at what I do… I mean, would I have turned out any different?

“For me, personally, I don’t think I could have or would have turned out any different from Eugene.”

During the meeting, all of Candice’s family were given a chance to ask Eugene any questions they had.

Candice knew what she wanted to ask.

“I said, ‘Eugene I want to say I forgive you, but before I do, I want to know one thing.’

And he said, ‘Sure what’s that?’

“I said, ‘Do you forgive yourself?’

“He was noticeably taken aback for the first time in the whole encounter and he said, ‘Every time a family comes here, that’s one question I pray they never ask me.’

“He looked away and he dabbed the side of his eye, because a tear had run down… and he looked back and said, ‘When you’ve done the things I’ve done, how do you forgive yourself?'”

Candice started crying, not for herself or her father, but – she says – because she realised that de Kock would never know peace.

“We were both two people that were broken, sitting in front of each other, and so it was a very transformative moment,” she says.

At the end of the meeting, Candice stood up first and walked over to Eugene de Kock and asked if she could hug him.

“He stumbled up to his feet and he held me in an embrace and he said, ‘I’m so sorry for what I’ve done, and your father would have been so proud of the woman you’ve become.'”

In 2015, Eugene was granted parole, something that Candice says she and all her family supported.

She knew that he had been working with the National Prosecuting Authority to find people who had gone missing years ago or to help locate bodies, to bring the victims’ families some solace.

“They had told me, ‘It’s very difficult to continue doing this work because there’s so many places where he tells us that these bodies are buried that we just can’t reach without him.’ So I thought if he was going to be more of a benefit to certain families outside of prison, then that to me felt more just than him rotting away in a prison cell, and having families out there mourning someone that they could never physically bury.”

For many of the victims of Eugene’s atrocities, forgiveness will never be possible. But for Candice, forgiveness has given her freedom from the trauma she felt as an innocent nine-year-old girl staring in disbelief at the horror of that picture.

“You can experience incredible trauma and it is not your fault, and a lot of people will say, ‘Well why is it on me to forgive when I didn’t do anything?'” says Candice. “But I would say to that, every time you give that incident or that person power, you are inflicting more damage on yourself, so you are re-traumatising yourself, and in many ways you are giving that person continued power over your life.”

Candice has written a book about her life entitled Forgiveness Redefined.

Interesting