Ghana risks miscalculating on its lithium strategy

While these engagements assuaged some of the concerns raised by civil society actors, other serious anxieties remained, some of which have been exacerbated by recent developments.

Last week, the MIIF invested $5m into Atlantic Lithium, the parent company of the country’s first lithium mining leaseholder, without any special sovereign interest protections, except an escrow arrangement of unclear structure. This author and others had warned that Ghana’s current equity stake of ~3% in Atlantic is exposed to massive dilution given the company’s very small market cap (currently about $163 million).

As it proves its business model, it would be able to and will need to, raise very large amounts of capital. Ghana’s financial constraints are such that its ability to participate in future equity rounds is heavily constrained. Anyway, the cash has been wired. At least, this time around, the country’s sovereign minerals fund, MIIF, did not try to pamper Ghanaians with any strange tales as to how the purchase price represents a capital gain, seeing as the company’s share price has more than halved since MIIF committed to buy.

Be that as it may, Ghana is now in bed with Atlantic Lithium, which makes heightened scrutiny of the company even more critical. Parliament will soon commence deliberations over the mining lease issued by the government to the company. Before sealing the deal, the nation’s representatives will do well to look at some of the still thorny issues surrounding Atlantic’s plans for Ghana very closely indeed. For now, let us only look at the issue of local value addition, one of the strategic redlines for Ghanaian civil society, as well as for the official political opposition.

As this author has said repeatedly, Atlantic’s struggling finances are clearly dictating some of its operating choices, with serious implications for the nation’s agenda to become a major electric vehicle (EV) value chain player by riding on lithium. If Ghana’s stated goal of refining lithium into value-added products is to be realised, then Atlantic must have the wherewithal to navigate alongside the nation’s strategists towards that objective, given its imminent control of large tracts of the country’s richest lithium deposits.

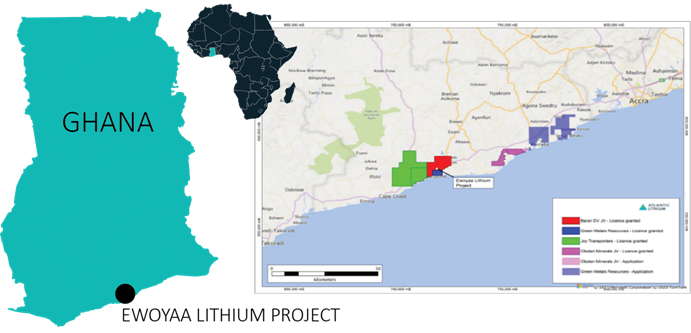

Even before it received its mining lease, that prospect was somewhat threatened because to raise money to fund further development, Atlantic had sold forward 50% of the output of the mine covered by its mining lease, Ewoyaa, to US-based Piedmont Lithium, itself another small mining company (market cap: ~$291 million). Still, about 50% of the material remained unpledged to support local refining into value-added products like lithium hydroxide and lithium carbonate provided the government was determined to see this happen. Except that things are not that simple.

Atlantic Lithium was expected to raise about half of the roughly $200 million (with Piedmont having committed to the other half) it needs to bring the Ewoyaa mine fully to life. Ghana had pledged about $28 million for 6% of Atlantic’s local subsidiary but these funds will only be released upon certain operational milestones being met. So, Atlantic went back to the market just before the holidays to raise another $5.21 million. Naturally, this doesn’t make enough of a dent. Atlantic needs more money.

Its market cap does not allow it to raise enough on the capital markets without diluting current shareholders to thin gruel. Its largest shareholders are two South African billionaires who want to take over the company, but the Atlantic board has demurred. The company is loath to raise debt because the resulting capital structure will add more layers of risk to its already elevated risk profile as a frontier mining junior with zero cashflows. Atlantic, faced with these daunting choices, hired Macquarie Bank to sell forward the remaining 50% of the lithium concentrate output upcoming from Ewoyaa to raise money.

Having received some offers from potential off-takers for the unpledged 50% of the yet-to-be-produced lithium concentrate, Atlantic and its advisors are weighing options regarding whom to partner. Obviously, it would be best if the partner was less hungry for cash than its current off-taker, and strategic financing partner, Piedmont. The question is: how involved is Ghana’s Minerals Commission in all these machinations?

Piedmont recently sold a nice chunk of its strategic equity stake in Atlantic to Assore, the company owned by the aforementioned South African billionaires, for about $7.8 million in cash to fund its own ventures elsewhere in the lithium world. Whilst this sale will not affect the 50% of Ewoyaa’s output that Piedmont is entitled to get when it pays up its share of the mine’s development cost, there are other signs that the company is deprioritising Atlantic and Ewoyaa.

A few days ago, Piedmont’s Chief Operating Officer (COO), Patrick Brindle, who had joined the Atlantic board to support the effort of commercialising the Ewoyaa prospect, and of course to secure Piedmont’s interest by so doing, resigned from Atlantic. Coming on the back of Stuart Crow’s resignation from the Atlantic board, this loss of talent is somewhat significant, but the crucial fact is that Brindle left Atlantic to focus on Vinland Lithium, which Piedmont already owns a much larger share in, compared to Atlantic, and whose Killick project is in geoeconomically familiar Newfoundland, in Canada’s easternmost corner. There are now serious concerns about whether Piedmont is fully committed to the Atlantic asset in Ghana.

From a Ghanaian public interest point of view, however, the real issue is how the government can continue to insist with a straight face that local refining is still on the cards when all the lithium is being sold forward in the form of concentrate because its strategic partner is financially constrained. In fact, Atlantic insists that it will operate the Ewoyaa mine for nine months using a very basic “dense media separation” setup before adding more sophisticated floatation and magnetic separation components in a modular component downstream when it has made enough money. The simple rule of thumb in lithium economics is that the higher the lithium oxide content of whatever mine output is being sold, the higher the value contribution. Increasing the lithium oxide content often involves investment in more sophisticated separation equipment.

By making these project decisions to conserve scarce cash, Atlantic is denying Ghana the opportunity to earn higher returns from lithium for as long as such interim arrangements persist. And by selling forward all the lithium concentrate to companies that have refineries elsewhere, it is more or less preempting any outcome of the “scoping study” (not feasibility study) it has pledged to undertake to determine if local refining would be feasible.

There are of course other concerns about the pricing transparency of these off-take agreements and the commercially incestuous arrangements they engender, but for now, it is crucial that the government updates the nation about its latest plans for lithium value chain optimisation in Ghana in the wake of these developments.

Yesterday, this author contrasted Rwanda’s more strategic approach to cultivating its lithium and EV value chain potential by quickly establishing a direct relationship with Rio Tinto (market cap: $119 billion), which had entered the Rwandan terrain initially through an earn-in arrangement with a company called Alterian. Alterian’s trajectory in Rwanda mirrors important aspects of Atlantic’s in Ghana. The Rwandan government has, however, determined that its national green-tech prospects will not be dictated solely by Alterian’s material constraints and is now hatching a broad engagement with cashflow-rich Rio Tinto to more strategically flesh out how a mine-to-battery roadmap should look like. There is, of course, absolutely no guarantee that Rwanda will succeed in this quest. But it is trying. Its President prioritised working sessions with Rio Tinto in Davos to advance previous engagements in Kigali and secured important long-term commitments. That is what striving strategically looks like, whatever the eventual outcomes.

Ghana’s strategists would do well to approach the green energy value chain opportunity represented by the recent lithium funds with similar, nay superior, savvy and energy.