Warning: This story contains distressing details from the start.

“This is like doomsday for me. I feel so much grief. Can you imagine what I’ve gone through watching my children dying?” says Amina.

She’s lost six children. None of them lived past the age of three and another is now battling for her life.

Seven-month-old Bibi Hajira is the size of a newborn. Suffering from severe acute malnutrition, she occupies half a bed at a ward in Jalalabad regional hospital in Afghanistan’s eastern Nangarhar province.

“My children are dying because of poverty. All I can feed them is dry bread, and water that I warm up by keeping it out under the sun,” Amina says, nearly shouting in anguish.

What’s even more devastating is her story is far from unique – and that so many more lives could be saved with timely treatment.

Bibi Hajira is one of 3.2 million children with acute malnutrition, which is ravaging the country. It’s a condition that has plagued Afghanistan for decades, triggered by 40 years of war, extreme poverty and a multitude of factors in the three years since the Taliban took over.

But the situation has now reached an unprecedented precipice.

It’s hard for anyone to imagine what 3.2 million looks like, and so the stories from just one small hospital room can serve as an insight into the unfolding disaster.

There are 18 toddlers in seven beds. It’s not a seasonal surge, this is how it is day after day. No cries or gurgles, the unnerving silence in the room is only broken by the high-pitched beeps of a pulse rate monitor.

Most of the children aren’t sedated or wearing oxygen masks. They’re awake but they are far too weak to move or make a sound.

Sharing the bed with Bibi Hajira, wearing a purple tunic, her tiny arm covering her face, is three-year-old Sana. Her mother died while giving birth to her baby sister a few months ago, so her aunt Laila is taking care of her. Laila touches my arm and holds up seven fingers – one for each child she’s lost.

In the adjacent bed is three-year-old Ilham, far too small for his age, skin peeling off his arms, legs and face. Three years ago, his sister died aged two.

It is too painful to even look at one-year-old Asma. She has beautiful hazel eyes and long eyelashes, but they’re wide open, barely blinking as she breathes heavily into an oxygen mask that covers most of her little face.

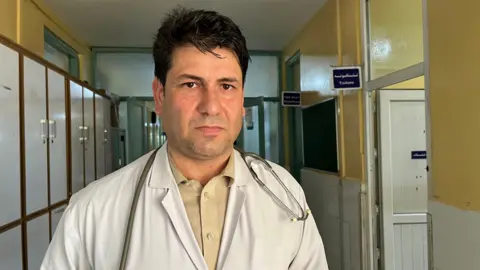

Dr Sikandar Ghani, who’s standing over her, shakes his head. “I don’t think she will survive,” he says. Asma’s tiny body has gone into septic shock.

Despite the circumstances, up until then there was a stoicism in the room – nurses and mothers going about their work, feeding the children, soothing them. It all stops, a broken look on so many faces.

Asma’s mother Nasiba is weeping. She lifts her veil and leans down to kiss her daughter.

“It feels like the flesh is melting from my body. I can’t bear to see her suffering like this,” she cries. Nasiba has already lost three children. “My husband is a labourer. When he gets work, we eat.”

Dr Ghani tells us Asma could suffer cardiac arrest at any moment. We leave the room. Less than an hour later, she died.

Seven hundred children have died in the past six months at the hospital – more than three a day, the Taliban’s public health department in Nangarhar told us. A staggering number, but there would have been a lot more deaths if this facility had not been kept running by World Bank and Unicef funding.

Up until August 2021, international funds given directly to the previous government funded nearly all public healthcare in Afghanistan.

When the Taliban took over, the money was stopped because of international sanctions against them. This triggered a healthcare collapse. Aid agencies stepped in to provide what was meant to be a temporary emergency response.

It was always an unsustainable solution, and now, in a world distracted by so much else, funding for Afghanistan has shrunk. Equally, the Taliban government’s policies, specifically its restrictions on women, have meant that donors are hesitant to give funds.

“We inherited the problem of poverty and malnutrition, which has become worse because of natural disasters like floods and climate change. The international community should increase humanitarian aid, they should not connect it with political and internal issues,” Hamdullah Fitrat, the Taliban government’s deputy spokesman, told us.

Over the past three years we have been to more than a dozen health facilities in the country, and seen the situation deteriorating rapidly. During each of our past few visits to hospitals, we’ve witnessed children dying.

But what we have also seen is evidence that the right treatment can save children. Bibi Hajira, who was in a fragile state when we visited the hospital, is now much better and has been discharged, Dr Ghani told us over the phone.

“If we had more medicines, facilities and staff we could save more children. Our staff has strong commitment. We work tirelessly and are ready to do more,” he said.

“I also have children. When a child dies, we also suffer. I know what must go through the hearts of the parents.”

Malnutrition is not the only cause of a surge in mortality. Other preventable and curable diseases are also killing children.

In the intensive care unit next door to the malnutrition ward, six-month-old Umrah is battling severe pneumonia. She cries loudly as a nurse attaches a saline drip to her body. Umrah’s mother Nasreen sits by her, tears streaming down her face.

“I wish I could die in her place. I’m so scared,” she says. Two days after we visited the hospital, Umrah died.

These are the stories of those who made it to hospital. Countless others can’t. Only one out of five children who need hospital treatment can get it at Jalalabad hospital.

The pressure on the facility is so intense that almost immediately after Asma died, a tiny baby, three-month-old Aaliya, was moved into the half a bed that Asma left vacant.

No-one in the room had time to process what had happened. There was another seriously ill child to treat.

The Jalalabad hospital caters to the population of five provinces, estimated by the Taliban government to be roughly five million people. And now the pressure on it has increased further. Most of the more than 700,000 Afghan refugees forcibly deported by Pakistan since late last year continue to stay in Nangarhar.

In the communities around the hospital, we found evidence of another alarming statistic released this year by the UN: that 45% of children under the age of five are stunted – shorter than they should be – in Afghanistan.

Robina’s two-year-old son Mohammed cannot stand yet and is much shorter than he should be.

“The doctor has told me that if he gets treatment for the next three to six months, he will be fine. But we can’t even afford food. How do we pay for the treatment?” Robina asks.

She and her family had to leave Pakistan last year and now live in a dusty, dry settlement in the Sheikh Misri area, a short drive on mud tracks from Jalalabad.

“I’m scared he will become disabled and he will never be able to walk,” Robina says.

“In Pakistan, we also had a hard life. But there was work. Here my husband, a labourer, rarely finds work. We could have treated him if we were still in Pakistan.”

Unicef says stunting can cause severe irreversible physical and cognitive damage, the effects of which can last a lifetime and even affect the next generation.

“Afghanistan is already struggling economically. If large sections of our future generation are physically or mentally disabled, how will our society be able to help them?” asks Dr Ghani.

Mohammad can be saved from permanent damage if he’s treated before it’s too late.

But the community nutrition programmes run by aid agencies in Afghanistan have seen the most dramatic cuts – many of them have received just a quarter of the funding that’s needed.

In lane after lane of Sheikh Misri we meet families with malnourished or stunted children.

Sardar Gul has two malnourished children – three-year-old Umar and eight-month-old Mujib, a bright-eyed little boy he holds on his lap.

“A month ago Mujib’s weight had dropped to less than three kilos. Once we were able to register him with an aid agency, we started getting food sachets. Those have really helped him,” Sardar Gul says.

Mujib now weighs six kilos – still a couple of kilos underweight, but significantly improved.

It is evidence that timely intervention can help save children from death and disability.