Ghana’s ambulance saga is crazier than you think

In December 2021, Ghana’s Attorney General started prosecuting the opposition parliamentarian (MP) giving the government its biggest headaches in the powerful finance committee mandated with clearing the government’s budget. As the “ranking member” of the committee, the MP was the Opposition’s point man on finance matters and was critical to holding the lines against approval of the 2022 budget.

Was the man guilty?

Coming in the wake of the government’s biggest second-term crisis in the newly split parliament, the prosecution was immediately condemned by some independent analysts, myself included, as pure political persecution and an attempt to undermine democratic accountability. It was apparent then, as it is now, that the MP had been unfairly targeted, and some of us said so.

Last week, the Court of Appeal issued a majority decision that more or less vindicated the persecution theory, and acquitted the MP, overturning an earlier decision by the High Court that his trial should proceed because the prosecution had established a prima facie case. For many of us, this was a resounding blow for democratic accountability.

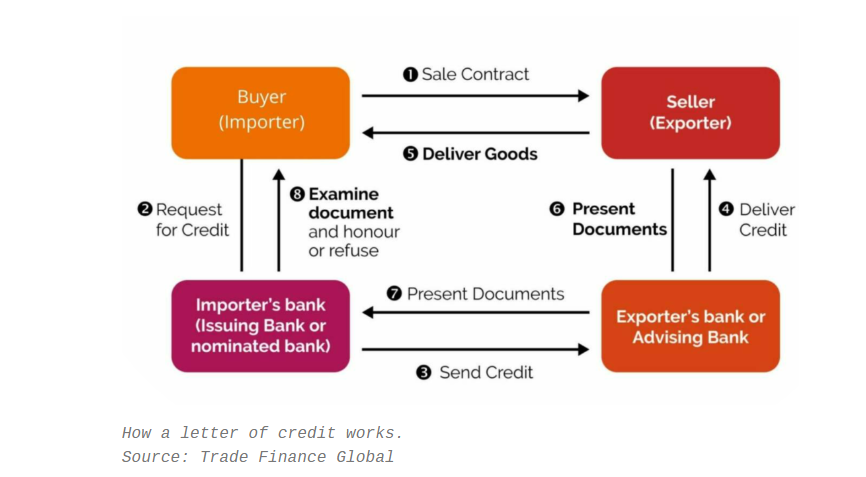

During the two and half years of the trial, commentators like myself have sparred over the MP’s liability in issuing a letter of credit (LC) as a payment guarantee to facilitate the delivery of 30 ambulances, abandoned since 2015 for not meeting specifications.

We have contended that anyone who understands the risk management features embedded in an LC would not mount a prosecution seeking to make an LC requester criminally liable for “causing financial loss” as a result of failures in an underlying transaction to which he was a mere bystander. The majority of the Appeal Court panel concurred.

Another issue of contention had been whether the accused opposition MP issued the LC without “due cause and authorisation.” Using an interpretation of an arcane aspect of Ghanaian case law, the High Court ruled that the burden of proving that he had authorisation rested with the accused because the government had framed their case in the negative (i.e. that he had no authorisation) and the factualness or otherwise of that claim was one best known to the accused. Of course, this is entirely philosophical. One could simply argue that the position of the accused is that he “did not act without authorisation”, which would be as “negative” a framing as “he did not have authorisation”. A similar reframing is possible for the prosecution’s position as well. How does such “burden shifting” in this specific instance, though, improve on the classical notion that the one laying the charge should prove?

In any event, in the public service, whether or not an actor has authorisation for an action is a matter of administrative record, and the government, in this case also the prosecution, is the keeper of records. This is not something that could be said to lie only within the personal knowledge of the accused or even his boss at the time, the substantive Minister of Finance, who was bizarrely not called to testify. The majority of the Appeal Court saw things in similar light.

But if he wasn’t, who is?

All this back and forth over what seems to be technical jousting and legal jargon has left some people frustrated. The prosecution was derived from an actual criminal investigation commenced four years earlier, in mid-2017. Thirty ambulances were imported into the country. Under some bizarre circumstances, they were declared unfit. About $2.6 million (EUR 2.37 million) were paid for them. What most people are keen to understand is simple: has there really been a financial loss to Ghana or not, and who is actually responsible? All this jargon-lading wordplay irks them. It comes across as another elite scheme to evade true accountability.

Another one for “State Enchantment”

In this short piece, I want to draw my readers away from the technical stuff and refocus on the actual financial loss to Ghana. None of my regular readers would be shocked if I start off with my usual refrain of “state enchantment“. This ambulance saga manifests all that is wrong about what governance has become in Ghana.

Knowing that no rational citizen will quibble if the government says that improving ambulatory care in the country is its mission, politicians have merely been hiding behind enhancing ambulance services, a “glorious” national objective, to dispense cash to cronies.

The criminal investigation commenced in 2017, but it was conveniently forgotten until the government needed a stick to beat the Opposition MP. From the outset, it was merely a cynical ploy to undermine an existing procurement program in order to benefit business cronies of the ruling party. To buttress these charges, let’s start at the beginning.

Ambling through Ghana’s ambulance history

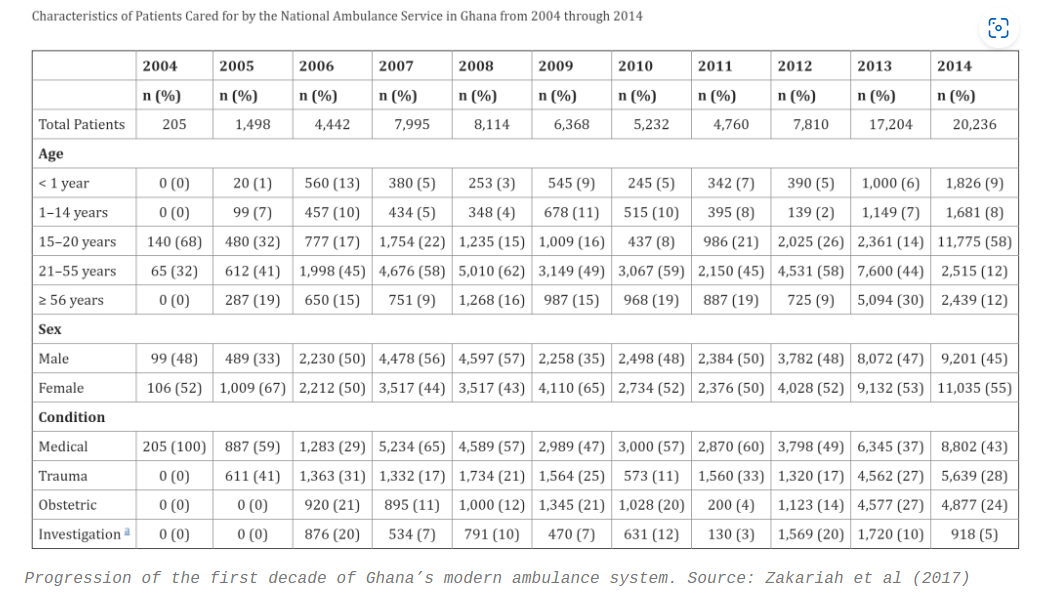

After the stadium crisis of 2001, the appalling state of ambulance services in Ghana was pushed into the limelight. The government commenced work to develop a national ambulance program aimed at transforming a landscape that was at that time highly fragmented. A few hospitals and clinics, mostly private, had some ambulances, but there was nothing like a national emergency hotline that one could call to request one if in mortal peril. In 2004, the National Ambulance Service was created and a pilot with 9 ambulances was started.

As with all policies in Ghana, and I say this with a great deal of consternation, nothing moves unless the procurement opportunities are clear. Thus, between 2006 and 2012, things moved very slowly. Only about 33 ambulances were active over the period.

In Ghana, “everything is procurement”

Then, in 2010, Universal Motors, a major car dealership in Ghana, saw an opportunity to make some good money whilst contributing to an obvious social good. It approached the government with a comprehensive proposal, complete with a funding source.

Universal Motors would import 161 Volkswagen T5 and Crafter base vans from its manufacturing partner, Volkswagen, in Germany to begin with. With a 10 million Euro facility, KfW-IPEX would finance a conversion of the base vans by engaging a specialist German company, Wietmarscher Ambulanz und Sonderfahrzeug GmbH. Voila, ambulances! Because of Ghana’s tendency to struggle with debt, the German Export Credit Facility, EulerHermes came on board to provide insurance cover.

But there have been simpler times

The Mills era was a simpler time in Ghana. Hence, this transaction sailed through relatively uneventfully and Ghana’s ambulance stock rose from 33 to 199. The casual reader would have missed several important issues raised by this transaction, which, however, merits attention.

The local company involved was the authorised distributor of the vans. The funding source was a development finance organisation with a long pedigree in financing public goods. The fact that a so-called “bilateral partner”, the German government to be precise, was involved meant that the funding was also concessional. Of course, it also meant that German companies had to benefit massively.

Until Ghana’s oil production gathered steam and the country doubled up on Eurobonds, transactions like this one were very common and they often run to a successful commercial close, even if the paperwork was always tedious and there was a tinge of “foreign interference” all over.

The involvement of Paris Club/OECD type governments in Ghana’s affairs is much resented by the sophisticated elite for its neocolonialist carryover, but it has had a predictable rhythm about it. Usually, well-established companies must be found. Paperwork must be thorough. And, vitally, a plan must exist to cover the basics.

The times are a-changing

As the country grew richer, political decision-makers began to have more resources in hand to move away from this model and experiment more. What could have been hailed as a great breakaway from neocolonialism however increasingly began to take the form with which we are now familiar.

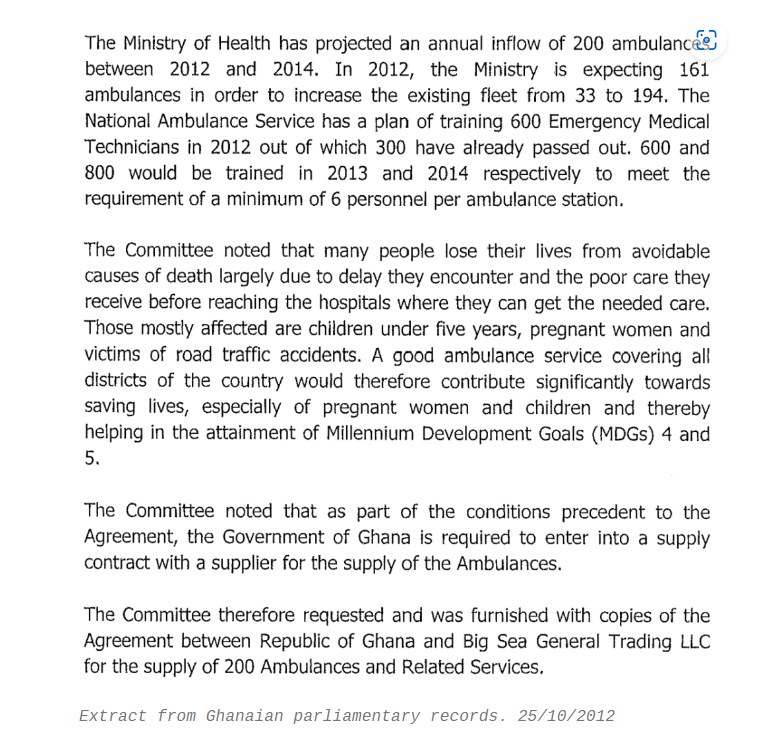

Soon after the arrival of the 161 ambulances, steps commenced to bring in more. Ghanaian experts advised the government that the country should aim for at least 1000 ambulances. But instead of relying on authorised distributors, manufacturer-authorised convertors, careful transaction structuring, and the like, creative experimentation with procurement entrepreneurs was in vogue. That is how come the next time a proposal arrived at the presidential complex to supply 200 ambulances from Jakpa@Business, this time around, everything was commercial. The bank involved was Stanbic, which was up for 15.8 million Euros. The van supplier was a company identified as “Big Sea General Trading Limited”, hardly a household name.

The pure commerciality of the transaction meant that the cost of the loan was 4% above the Eurobor rate. There were no development finance institutions to insist on insurance cover. And there was certainly no German government to ask uncomfortable questions about policy alignment and all that boring stuff. Furthermore, in this brave new world of procurement entrepreneurship, the state-business environment had become more competitive. Business actors backed by different political factions were constantly scheming and plotting.

The Order of Policy Confusion

When pursuant to the contract with Big Sea, the first tranche of 10 ambulances arrived, the reception party was pure confusion. Showing incredible resilience, the owner of Jakpa@Business, Big Sea’s local agent, continued to press. A further 20 ambulances were brought in. The Ministry of Health was at this point wracked by competing interests.

In the midst of the confusion, pre-shipment inspections were not done. The conversion process was delayed, and the conversion modules (the equipment used in transforming ambulances) were stuck at the port. Whilst the essential pieces had been procured, including Mercedes Benz 311 vans (more robust than the 309 versions contemplated in the contract) and conversion kits, project management essentials were completely derailed by a dysfunctional policy environment in which ministries, agencies, contractors, and the cabinet itself, were clearly misaligned.

Four years is how long it took for all this drama to play out. Four years. But by late 2016, after a raft of court cases, an Attorney General opinion, threats to sue for breach of contract, and a changing of the guard in ministerial ranks, a settlement had been reached and the conversion of the 30 ambulances could proceed so that the rest of the contract could be executed. No money really needed to be lost from this point onwards. Then governments changed on 7th December 2016.

New King, New Law

Despite the entreaties of Jakpa@Business and Big Sea, the new government would have nothing to do with the ambulances for reasons that shall soon become clear.

It is important to note here that, on paper, the Big Sea ambulance transaction followed the same essential technical template as the Universal Motors one. Eligible base vans are procured from a reputable manufacturer like Mercedes or Volkswagen. A company that specialises in outfitting vans into ambulances is contracted. And then the requisite inspections, validations, trainings, and handovers are performed. The diligent reader can examine sample protocols used in the most advanced countries for a grasp of the essentials. The attempts that have been made in recent times to suggest that the Big Sea procurements were inherently technically flawed are pure propaganda.

What is true is that the way governance is done in Ghana had started changing dramatically between the two transactions making implementation of the Big Sea ambulance project more likely to fail due to far more aggressive political-commercial interests than Ghana has historically known in the Fourth Republic.

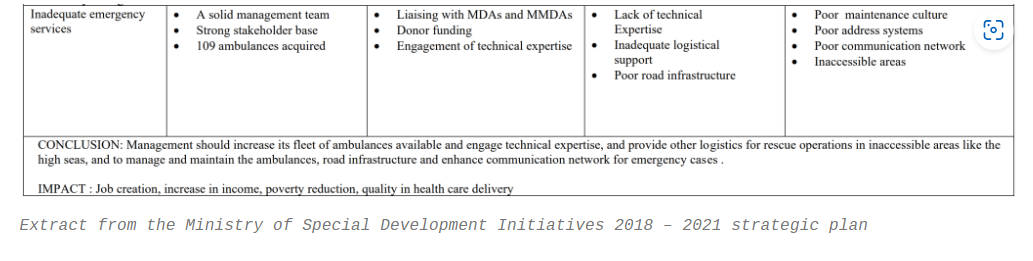

As soon as the new government was sworn into office, it started working on its “own” ambulance procurement scheme. Even though only 55 ambulances were functional by 2019, the government refused to engage Big Sea and Jakpa@Business to complete the ambulance conversion and validation process under the terms of the updated settlement. The 30 imported ambulances were left to rot.

Having crafted a “One Constituency One Ambulance” (OCOA) manifesto promise ahead of the 2016 elections, the country’s entire ambulatory care policy was now held hostage to the current flavour of partisan politics in which every government policy must also be thoroughly commercialised for the benefit of political favourites in the business realm. The more upstart these favourites are, the better.

By May 2018, the mushroom ministry set up to advance the OCOA scheme had already made arrangements for 109 ambulances.

By 2020, 309 new ambulances, based on the same Mercedes Sprinter Van 311 models as the Big Sea ones, had been procured. If the reader is paying attention, they would no doubt have noticed that at no point during this period had any attempts been made to hold Big Sea and/or Jakpa@Business, or indeed any former public servant, liable for any infractions. The government was too busy trying to forget that the country had signed a contract for 200 ambulances for which funding had been ratified by the Parliament itself.

It is only getting interesting: Enter Luxury World

In keeping with my belief that in Ghana anytime a new negative trend is discovered, it can only get worse, the procurement entrepreneurship hustle had, by 2020, attained proportions of unbelievable perversity, enriched as it were by state enchantment. In true form, the procurement activities surrounding the One Constituency One Ambulance (OCOA) scheme have been truly fetid.

Somehow, companies claiming to have participated in a competitive tender ended up forming a consortium to execute the OCOA deal, clear and ample evidence of collusion and bid-rigging.

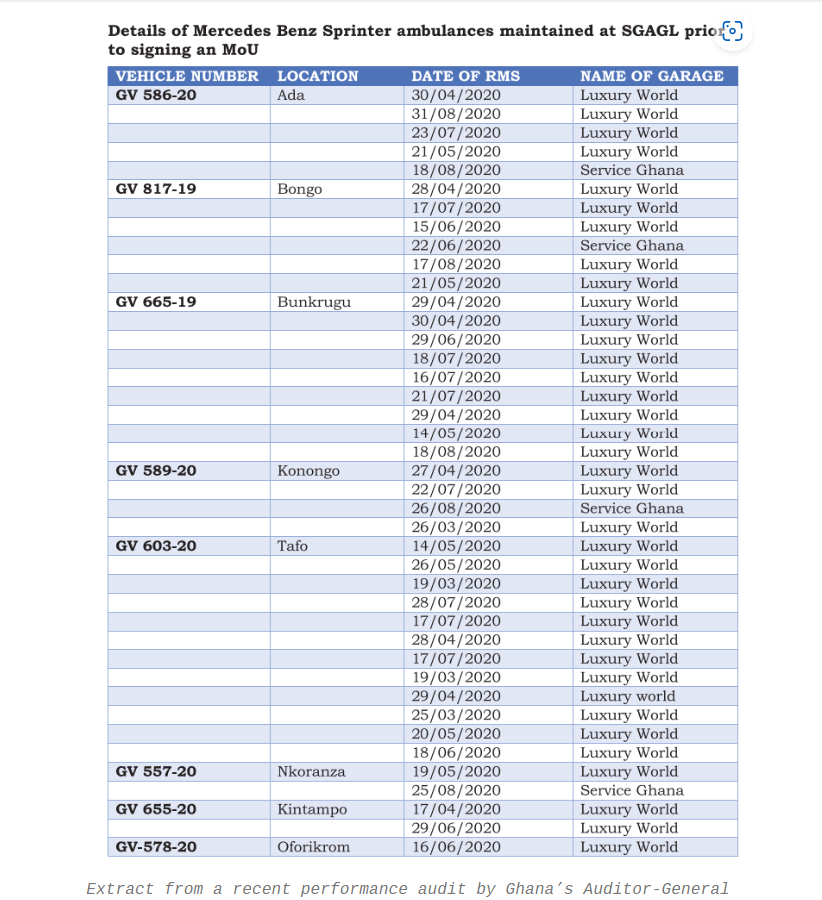

Somehow, this “consortium” has also managed to wring from the hands of the National Ambulance Service (NAS) the lucrative servicing and maintenance mandate even though it has been using the staff and some of the facilities of the same NAS. A member of the consortium called “Luxury World Autogroup”, rather than the consortium that purportedly holds the contracts, has become the primary service provider to the NAS. Virtually all garage contracts now go to Luxury World.

There is always a shadowy character lurking in the nooks

But who is behind Luxury World? A colourful figure with a string of convictions in the United Kingdom and noted for frequent brushes with the law in Ghana. Someone supposedly under investigation by the EOCO, the country’s organised crime agency, for forging invoices related to spare parts for the same ambulance program. This very individual is currently in court fighting another politically connected individual believed to have helped broker some of the deals with the government. In the court proceedings, he is alleging the use of national security operatives to harass and molest him and his staff. So much drama! You literally couldn’t make it up!

Meanwhile, ambulance services continue to sink

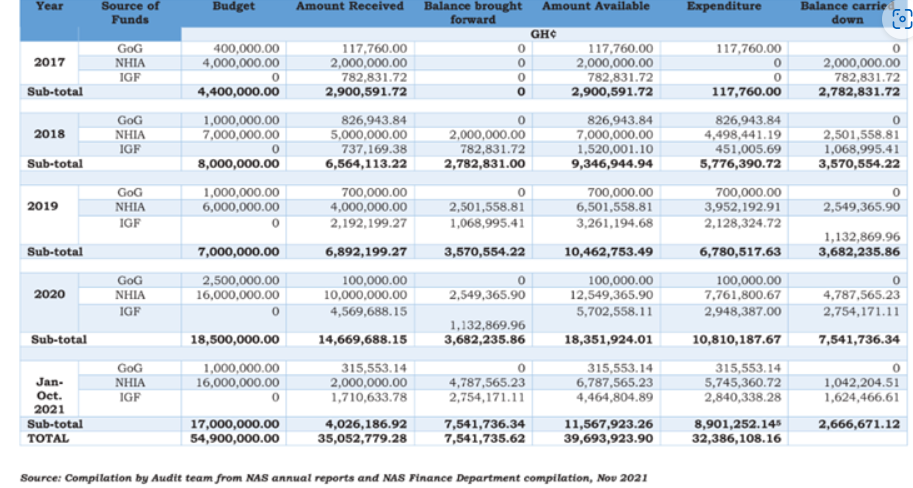

The government of Ghana continues to borrow heavily to sustain these procurement-juicy schemes. Yet, the actual policy for ensuring that these ambulances deliver effectively for the people has never had much attention. Over the years, funding for the actual operations of the ambulance service from the government has dried up.

Even as the central government continues to funnel millions of dollars into the pockets of connected political “procurepreneurs”, it is now responsible for less than 3% of the funding that goes into the actual running of the ambulances. Patients now expect to pay before ambulances are dispatched to them against the clear provisions of the law. The government is unable to procure insurance cover for all the ambulances, which means that a serious breakdown often requires decommissioning or, even worse, poorly advertised auction to crony bidders.

Worse still, ongoing parliamentary inquiries by a crusading MP suggest that the invoice inflation problem is not confined to the Chief Executive of Luxury World. It is systemic and rampant in the One Ambulance One Constituency program, and that tallied altogether the cost of these infractions and cost-inflation may exceed $20 million so far.

But isn’t all this natural for “emerging” nations?

For those readers who may be tempted into believing that all this procureneurship and state-business enchantment stuff are standard play in the evolution of modern nations, I will urge you to think again. It is true that in the industrial transformation of Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia and the few Asian countries that have grown their economies the fastest from the last century to date, state-business entanglements were par for the course.

What is happening in Ghana, however, is nothing like the very deliberate efforts to build capacity within the domestic private sector, with kickbacks to the political class paid out from productivity gains, that occurred in the most dynamic Asian states. In Ghana’s model, there is no serious capacity building or medium-term productivity gains. The disorganised process proceeds in fits and starts, with random beneficiaries, and the siphoning of public funds ultimately into foreign hands since the business actors in the rackets barely learn to add serious value.

Remembrance of things colonial

But back to ambulances. The funny thing in all of this is that even in colonial times, Ghana had an organised ambulance service, albeit one with British imperial baggage: the St John Ambulance Ghana service, a mission chartered by law after independence.

Today, Ghana is the only major Commonwealth African country where St. John Ambulance no longer routinely operate ambulance services. Contrast this situation with that of Kenya, for instance, where St John doesn’t only continue to run ambulances but is even in talks to set up a major dispatch facility backed by the government.

Having been denied the public funds due them by convention, St John Ambulance in Ghana has now been reduced to offering first aid training and hiring vans for the occasional intervention. Their decades of experience in ambulance management and global connections have never been properly tapped by any government in the Fourth Republic.

It is much too easy to say that in the recent ambulance prosecution saga, we should simply focus on holding to account the individuals who caused the supposed loss of ~$2.6 million. The question, after reading all the above, dear reader, is whom would you charge for “causing financial loss” to Ghana?