Hollywood’s first Asian American movie star has long been misunderstood. A new book seeks to change that

About two decades ago, Katie Gee Salisbury glimpsed a photo that would stay with her for years to come.

The black-and-white image depicted a sea of parade-goers surrounding a convertible. In the back seat was a Chinese American woman looking ever so chic and glamorous.

Salisbury, a fifth generation Chinese American with deep roots in Los Angeles’ Chinatown, was immediately captivated by the woman. It was her first day as an intern at LA’s Chinese American Museum, and a curator explained that she was looking at Anna May Wong: an internationally famous actress from the ’20s and ‘30s who is considered Hollywood’s first Asian American movie star.

“I wanted to know more about who this woman was,” Salisbury says. “I couldn’t believe no one ever told me about her.”

That photo ultimately inspired Salisbury’s new book, “Not Your China Doll: The Wild and Shimmering Life of Anna May Wong,” which published on March 12.

As Salisbury readily admits, she’s not the first person to chronicle Wong’s life and career. But she felt that other biographies of the actress, though notable contributions to the study of Wong’s life, left something to be desired.

“A lot of them are written by academics or by men, and I always personally felt that they were missing the perspective of an Asian American woman,” she adds.

Previous biographers largely painted Wong as a tragic figure, according to Salisbury, overemphasizing rumors about her sexuality, her struggles with alcoholism and her decision to never marry.

In “Not Your China Doll,” Salisbury set out to tell a different story.

It’s true that Wong’s life was not without challenges — because of Hollywood’s racism, she was too often relegated to stereotypical, side parts and lost countless roles to White actors in yellowface.

But as Salisbury points out, she had plenty of triumphs, too. Her title role in “The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong” marked TV’s first Asian American lead. The trailblazing star also captured the hearts of audiences and critics, and ultimately forged her own path in an otherwise prejudiced industry.

Salisbury spoke with CNN about how Wong defied stereotypes of Asian women, how Hollywood has changed since Wong’s time and about how her own Asian American identity shaped the book.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You write in the preface that in addition to consulting primary sources and Wong’s niece, you also drew upon your “own personal and familial knowledge of what it’s like being Asian American in this country.” How did your identity shape how you told Wong’s story?

I have a somewhat unique position. On the one hand, my Chinese American family has been in this country for five generations. We immigrated from the same place in southern China as Anna May Wong’s family, so there was definitely a kinship there just in the family history.

I myself am mixed. I’m half Chinese and half Anglo Irish. I grew up in a very Asian community. But at the same time, people don’t always recognize me as Asian, so I don’t necessarily have the exact same experience that Anna May Wong and a lot of Asian American women have.

What I really tried to do was just embody what I thought was Anna May Wong’s experience by just tapping into my own experiences and the experiences of my friends and family that have been shared with me. I put myself in her shoes when certain things happened to her.

A good example I talked about in the book is when she was making “The Thief of Bagdad.” It was reported by Douglas Fairbanks — the star of the film and the producer — that there was an incident in which Anna May Wong wouldn’t put on the “Mongol slave” costume.

The reason Fairbanks cites (for Wong apparently being difficult on set) is that the publicity guy got her Chinese name wrong — instead of “two yellow willows,” he said “two yellow widows.” The story to me just rang kind of phony, because I can’t imagine someone would get mad about something that sounds so silly.

So not knowing what happened, I’m trying to think if I was Anna May Wong and I was 18 years old at the time, this is her big break. Douglas Fairbanks is one of the most famous people in Hollywood and the world. Everyone knew his film was going to be a huge blockbuster, and she had a very prominent role in it. So what would make her step away from the set and refuse to put her costume on?

It had to be something pretty serious. To me, knowing her attitude already at that age towards the racism that she experienced, she was prepared to fight back. She wasn’t going to let people denigrate her in that way. So using circumstantial evidence, but also just understanding her position in that situation, my working theory is that someone made a racist comment to her, and she was like, “Well, I’m not gonna settle for this type of behavior, even in the most important film of my career.”

That’s an example of how I tried to embody what her perspective might have been.

What’s the meaning behind the book’s title “Not Your China Doll”?

When I started thinking about this book, I wanted to reframe the narrative around her life.

So much of it is focused on the fact that she had to play stereotypes and the disappointment of not getting the lead role in “The Good Earth,” which would have potentially changed her career and her legacy in some people’s eyes. (Note: A White actor was cast as Chinese farmer Wang Lung, so Wong was ultimately passed over for the role of his wife O-Lan in favour of a White actress because of rules that outlawed the portrayal of interracial romance on screen.)

Also the fact that her later years were really difficult. She struggled with alcoholism. She struggled with the fact that she couldn’t play the same types of roles she did when she was young. The way that (her story) gets told makes her life sound like a tragedy and that she had no control over it.

There’s a lot to what she did that has a certain defiance and righteousness to it.

From my perspective, she had so much agency. She exerted so much resiliency and control over her future. There’s a lot to what she did that has a certain defiance and righteousness to it.

“Not Your China Doll,” because she is always called the China doll, just felt appropriate. It’s not only a phrase that applies to Anna May Wong, but a lot of Asian American women feel that they’ve been objectified and exoticized in the same way.

Was there anything you learned about Wong during your research that surprised you?

The thing that really impresses me still today is just how confident she was in herself and in her belief that she deserved more. She was always willing to fight for that. She did so in a very diplomatic and shrewd way — she didn’t outright complain, but she found other avenues to the thing that she wanted.

Her decision to go to Europe in 1928 was a very difficult decision to make. To leave Hollywood was a really scary thing, because most people who did that didn’t come back in a successful way. She was only 23 at the time, and she says herself in one of her memoir pieces that many people told her not to do it. But then she says, “I just made up my mind that I would go.”

I just love that confidence and that determination that whatever happened, she was going to make it work because she believed in herself. And honestly, if she hadn’t gone to Europe, I’m not sure that we would be talking about her today. That move really made her career.

One striking facet of Wong’s story is how everyone around her seemed to recognize her talent and star power, but she could never achieve her true potential because of how deeply racist Hollywood and the US overall were at the time. How did the country’s racial politics affect her career?

It’s hard for us to imagine how limited certain people were in how they could move through society. There’s a story that I just recently found where she was walking into a movie premiere and someone called her a “Chink” and said “Go back to where you came from” or “go back to the laundry.” But at the same time, because she was seen as a little bit more of an oddity, people were a little bit less in her face. She had much more mobility than she would if she had been a Black woman.

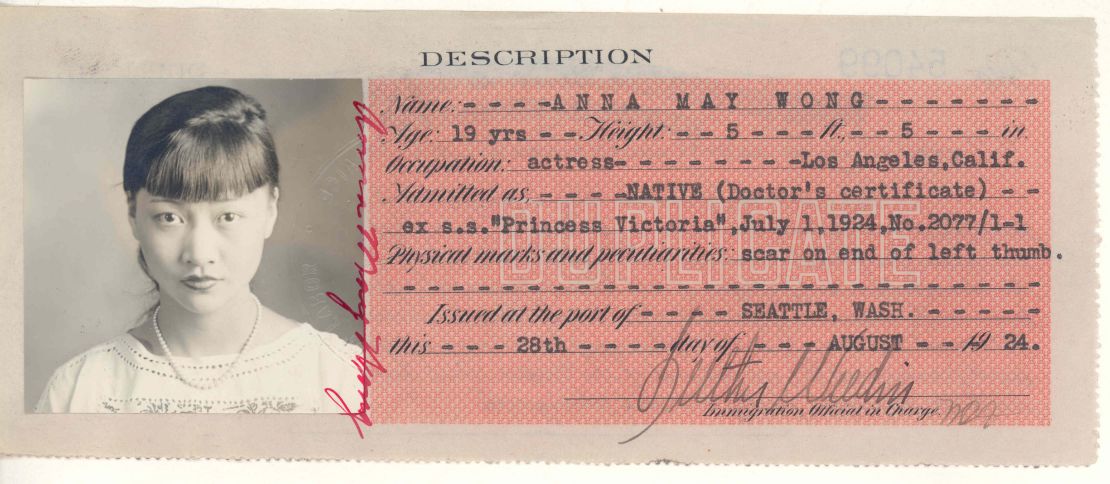

From 1909 to 1928, the US government required people of Chinese origin to carry certificates of identity. Anna May Wong, despite being a third-generation American and a movie star, had one pictured here. US National Archives and Records Administration

There were also plenty of people who loved Anna May Wong and wanted to see more of her. It’s a very complex situation for movie studios then because they’re trying to tow a certain line. In the late 1920s, they had all these scandals, and they’re trying to clean things up and seem more appropriate. Part of that is limiting the types of roles that Anna May Wong can have.

But at the same time, in the 1930s, there’s the Hays Code (a set of self-imposed guidelines on major film studios that prohibited nudity, miscegenation and other content), but they made exceptions all the time in other situations. So it was a code that was applied very selectively according to their whims.

I do believe that at the end of the day, if producers and studio heads had wanted to make her an A-lister they would have, but they found excuses not to.

How does Wong’s legacy show up today?

So many Asian and Asian American actors in Hollywood today really look up to her as a source of strength and inspiration. (The landscape for Asian American actors) has definitely changed in a really good way in the last few years, but looking at her legacy is a reminder of the fact that we’ve had to wait 100 years for this type of progress. She was there from the very beginning, so why has it taken so long?

It’s not that Asian Americans weren’t there. But the institution was built in such a way that it pushed them out.

Anna May Wong was acting before the Oscars even existed.

Watching Michelle Yeoh win the Oscar for Best Actress last year was such an emotional moment for me and for so many people. But I like to remind people that it took 95 years to get to that point. Anna May Wong was acting before the Oscars even existed.

What do you feel has changed about Hollywood since Wong’s time? What, if anything, has stayed the same?

“Crazy Rich Asians” changed the game because it showed people that you could have a film that was led by an Asian cast that is commercially successful. Of course, there’s baggage that comes with that because then (studio heads) want a certain formula and they want it to always be “Crazy Rich Asians.” We want to tell a lot of different types of stories, not just ones like that.

I do think that there has been a concerted effort among Asian Americans in the industry. There’s so many more people who are higher up in these organizations, whether they’re production companies or studios, who are helping to make decisions or advocating for these types of stories.

The other reason really is just that there’s so much more opportunity now. You don’t have to go through Hollywood in order for your film to be successful and to reach an audience. You can fundraise, self-fund, produce it independently and hope it gets attention at a film festival.

Watching “Everything Everywhere All At Once” — who would have thought that a film like that could win Best Picture at the Oscars? There’s so many more avenues now to make films and to tell stories that just weren’t available during her time.

Knowing what you know about Wong, how do you think she would feel about the plethora of Asian American stories on screen today?

I think she would be so happy and over the moon to see what’s going on today. I almost think it’s beyond her wildest dreams. She was the only one, and now there are so many people in the Asian American cinematic universe.

Hopefully, she would be an even bigger star. It’s hard to compare just because her acting style is a little bit different from what we’re used to today. But she was also a pretty fast study, so I think she’d figure out a way to be involved.

What films featuring Wong do you recommend?

For her silent era, “Piccadilly” (1929) or “Pavement Butterfly (1929).

“Shanghai Express” (1932) is a great one from the sound era with Marlene Dietrich. My only complaint is there’s not enough Anna May Wong in it.

She was able to create a storyline where the Asian actors are the heroes and heroines.

One other later film I would suggest would be “Daughter of Shanghai” (1937). It was a B-movie, but she had more influence over it so she was able to create a storyline where the Asian actors are the heroes and heroines and all the bad guys are played by White actors. And she gets a happy ending.

What do you hope readers take away from Wong’s story?

I’d like for readers to appreciate all of the things that she accomplished in her career, rather than dwelling on some of the more tragic things that happened.

Yes, there were a lot of things that she had to struggle through. Despite it all, she really found a way to come out on top. The fact that she was weeks away from beginning rehearsals in “Flower Drum Song” (Note: Wong was originally cast as Madame Liang in the film adaptation of the 1958 Broadway musical but died shortly before production began), which would have been a huge milestone to have an all principal Asian cast, just tells you how far she went with her career.

It’s a shame that she didn’t get to do it, but that doesn’t take away from the power of what she did.