Why Ghana’s first Lithium agreement shouldn’t be ratified as is

Mining in Ghana: A long and twisted tale of disappointment

Civil Society advocates active in the natural resources policy space in Ghana have been left disappointed by the failure of imagination among politicians and senior civil servants negotiating Ghana’s first lithium mining lease.

It is safe to say that almost no Ghanaian is happy about the historical and contemporary reality of mining’s contribution to the country. For a country that has a 500-year reputation for being a haven of gold (with large-scale commercial gold mining dating from at least 1897), was once the 5th largest producer of the metal, and currently the largest in Africa, many Ghanaians look around them and frown when they don’t see the glamour of Johannesburg’s Sandton.

The Manic Past of Lithium

News that Ghana had signed a mining lease with an Australian junior miner to produce lithium from 2025, therefore, raised hackles. Coming just weeks before the COP28 Summit in Dubai, with all the razzmatazz around green energy and the “climate transition“, the question on every Ghanaian’s lips was: “Would lithium be the game-changer when oil and gold appear to have disappointed”?

Answering that question, especially about the agreement Ghana has just signed, requires a bit of a detour to explore why such hype has been building around lithium in the first place.

Highly reactive and inflammable, lithium, the lightest metal on Earth, now affectionately referred to as “white gold”, was first detected as a trace element in 1817 and isolated in 1855. For decades thereafter, its renown was gained by its use by some physicians in the management of mania, depression and bipolar disorders more generally. Hardly surprising then that it is inducing such frenzied mania today.

The Lithium Rush

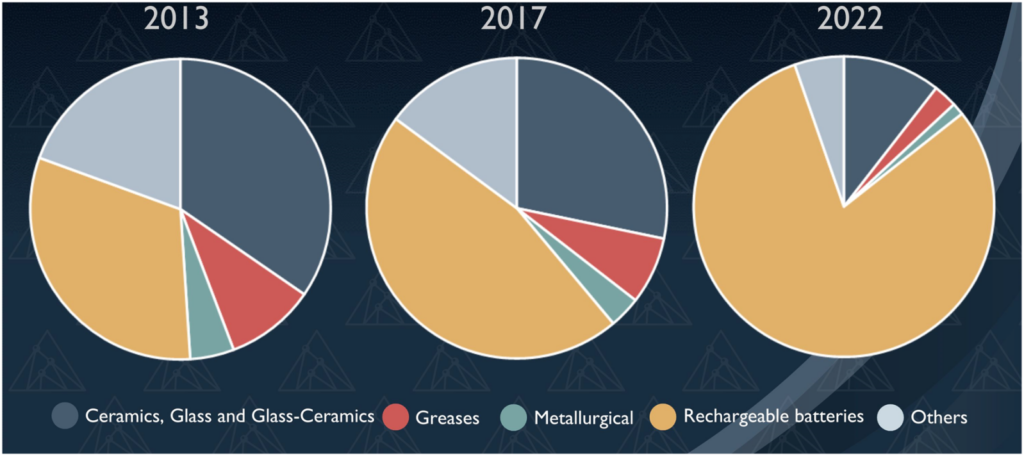

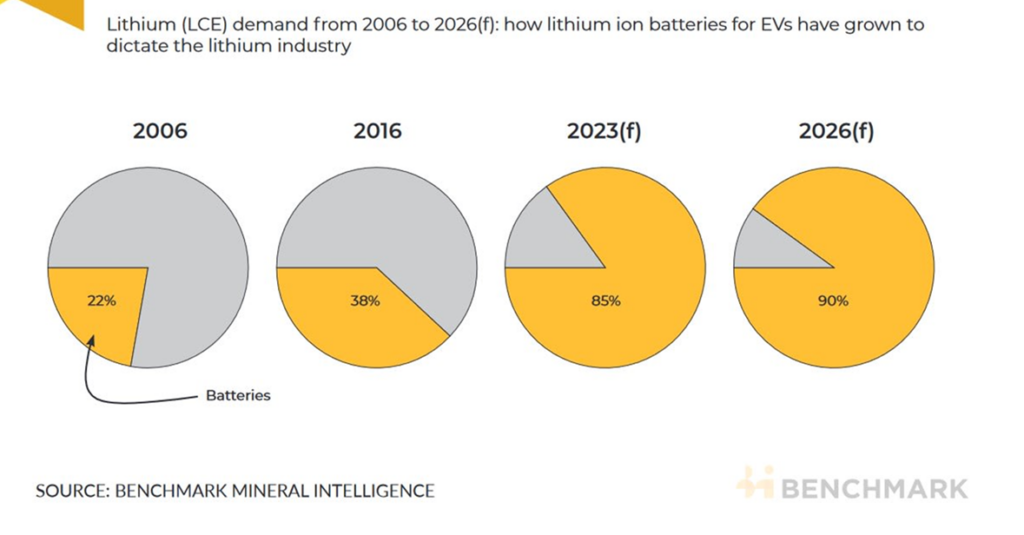

As the 20th century proceeded, lithium began to find more applications across areas such as ceramics, glassware, polymers, castings, medicines (of course), and others. A few years ago, however, one use of lithium has far exceeded all others: batteries to power the electric vehicle (EV) boom. Today, more than 85% of all lithium demand is for use in lithium-ion batteries.

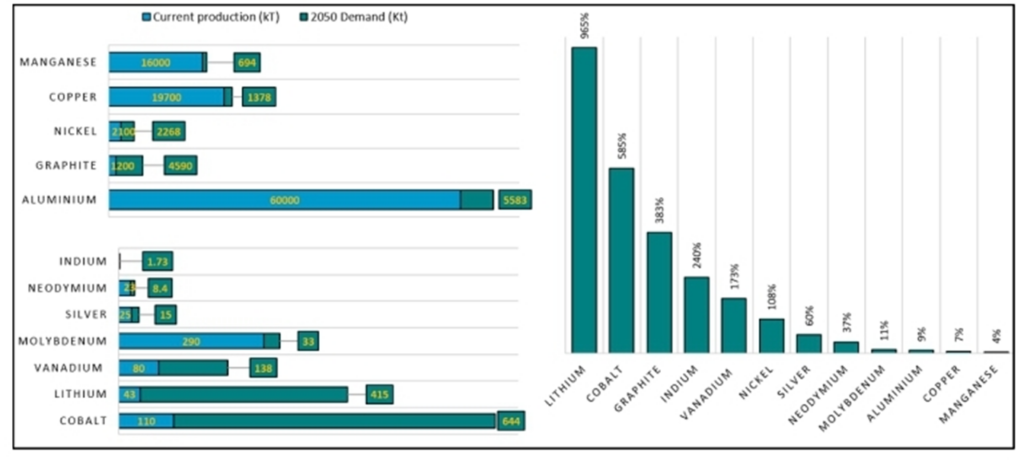

Some analysts believe that by 2050, lithium would have seen the fastest growth among all the minerals usually associated with the green transition.

Lithium chemistry can confuse you

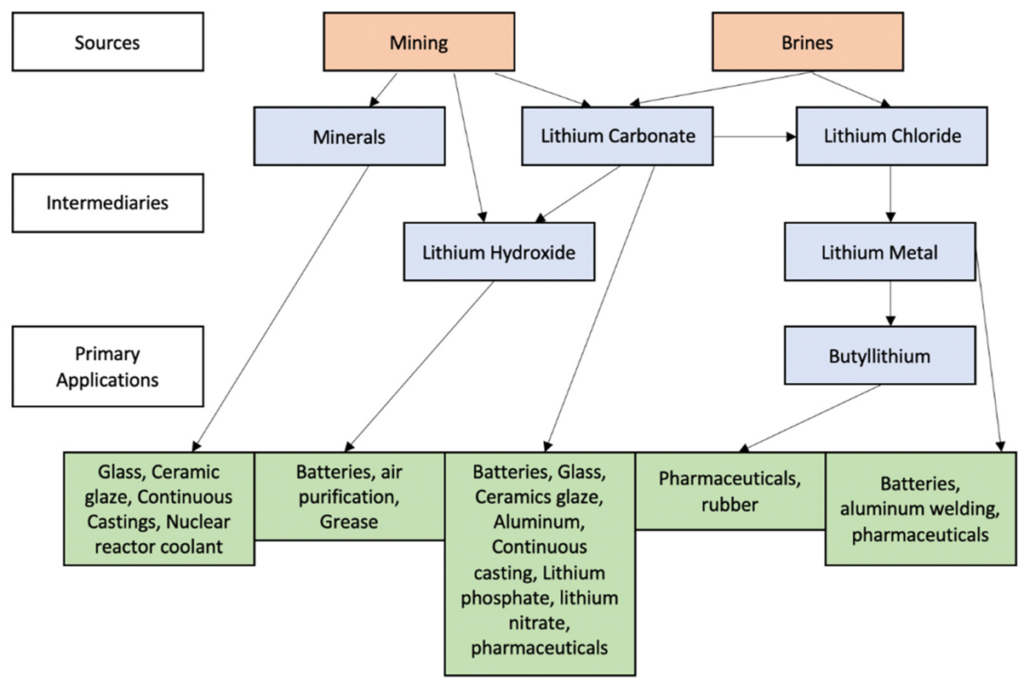

Because lithium is such a reactive element, unlike, say, gold and aluminium, which are considered “inert” (relatively so in the case of the latter), its economic importance is often expressed through a bewildering array of intermediate and end-state compounds, such as lithium hydrochloride, lithium carbonate, and, to a much lesser extent, lithium bromide.

Therefore, when discussing lithium economics, one should always be very clear about which chemistries, chemical pathways, compounds and salts are involved. Much depends on how lithium combines with other substances, either naturally or during processing, to arrive at a particular economic use case.

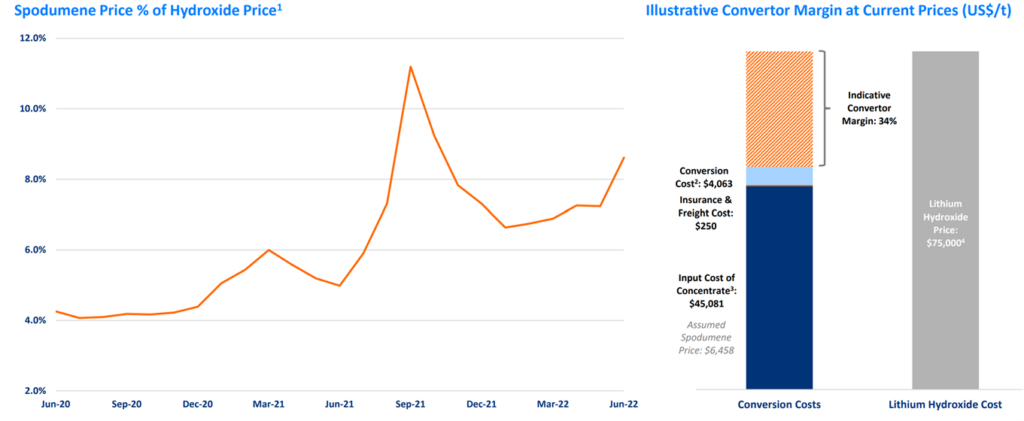

For example, during the recent bull era, when lithium prices exploded, the margin on refining the concentrates of spodumene, the most common rock ore of lithium, into lithium hydroxide, one of the compounds that in its most refined state goes into batteries, was about 35%.

Depending on the relative inventory levels of spodumene concentrate and lithium hydroxide in dominant markets like China, that margin can fluctuate much more crazily than is the case in some value chains we are more familiar with like cocoa, gold and bauxite. Again, this calls for smart economic contracts that are somewhat flexible enough to ride the storms.

The Economics of Ghana’s lithium deal draws scrutiny

Given this context, civil society analysts in Ghana have been painstakingly poring over the Definitive Feasibility Study (DFS) submitted in the disclosures of Atlantic Lithium, the company recently granted Ghana’s first lithium mining lease (subject to parliamentary ratification), to the alternative submarket of the London Stock Exchange (and concurrently to the Australian Securities Exchange, where it is also listed). The reader may find the highlights below.

The easiest observation to make from the DFS is that the proposed lithium operations are juicily profitable. For the company. With a post-tax margin of roughly 23%, and relatively low capex (revised a number of times to about $195 million), investors look to be sitting pretty. Due to Atlantic Lithium’s relatively conservative posture in the DFS at the height of the lithium boom, its numbers are only looking a bit off (the projected price of its highest grade concentrate – SC6 – for instance has had to be revised downwards from $1695 to $1410 per tonne according to recent statements by Ghana’s mineral authorities).

What civil society observers are asking is whether the Ghanaian people, by law the ultimate owners of the resource, would be just as comfortable over the 12-year course of mining of these deposits in the Ewoyaa region of the country’s central coast. We will come to that shortly.

Putting Ewoyaa in context

Zimbabwe is Africa’s largest producer of lithium. It is believed to hold the world’s fifth or sixth largest reserves of the metal. Yet, the country is on course to make just about $250 million from the mineral this year, out of total mineral earnings of about $5.67 billion (2022).

Bear in mind that Ghana, in a good year, can generate more than $6.6 billion from gold exports (how much of that actually stays within the economy is a different matter). Despite all the hubbub about Africa’s lithium, the continent currently holds only about 5% of the world’s known reserves. All this to say that the lithium game is just beginning. Any premature excitement is likely to be, well, premature.

Lithium does deserve special attention

The above notwithstanding, there are interesting aspects of the lithium value chain that requires that countries not take a business as usual approach. Compared to, say, cocoa, where the cocoa beans often struggle to capture even 3% of the value of marketed outputs, things can be different in the case of lithium.

Provided one refines lithium into the form, such as lithium carbonate or hydroxide, that can be used in battery components like the cathode, one can capture 30% of the value of the battery. Compare that to, say, cocoa powder, where there have been years in which margins have been actually negative (i.e. producing cocoa powder makes less money than leaving the cocoa in beans form).

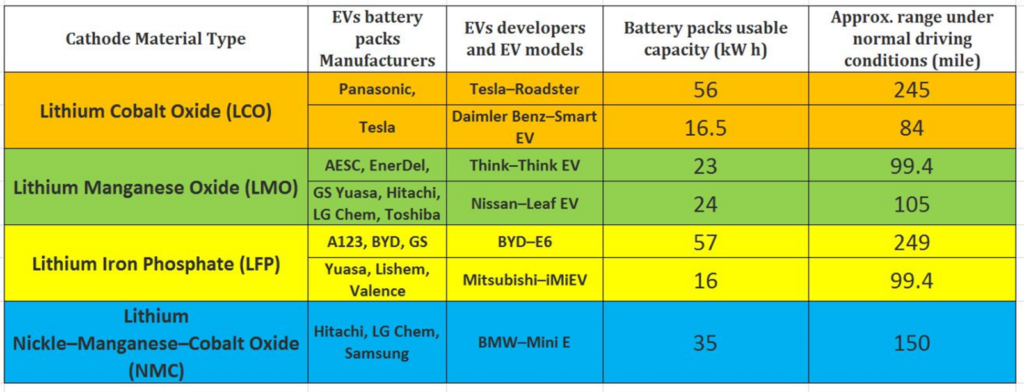

These value chain margin analytics are further compounded, as hinted earlier, by the fact that valuable lithium end-products like batteries often require other green minerals to make, interlinking the economics of lithium with that of various strategic complements. Below, the reader may scan several battery technologies and notice two things: the involvement of other green minerals besides lithium and the tendency of major buyers of lithium end-products like batteries to make a strategic commitment to one combination/configuration of green minerals or the other.

With that highly condensed crash course out of the way, we can begin a discussion about Ghana’s contract with Atlantic Lithium and start to shed light on why some in Ghanaian civil society believe that government Ministers and the officials advising them are being too self-congratulatory.

How Unprecedentedly beneficial was the lithium deal?

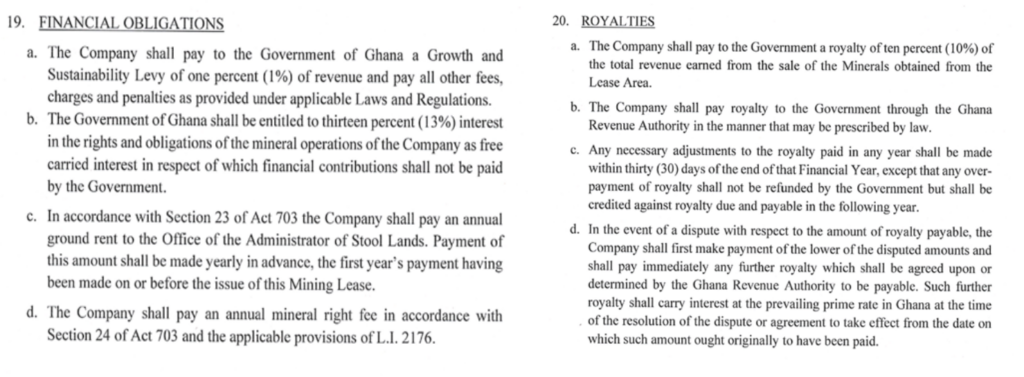

First, the money (see key terms in the snapshots below). The government’s big case is that it has secured concessions from Atlantic Lithium that no government has been able to obtain in the country’s history. If this is based purely on how the gains from the resource are to be shared between the government and the investor, in ownership and monetary terms, then that fact is simply incorrect.

It is common knowledge in Ghanaian natural resource settings that the share to the state of resource gains was heftier in the 1970s and the early 1980s, and even after reforms came in the late 1980s, those terms were generally more favourable than what ensued in the subsequent decades.

In the 1970s, the Ghanaian government introduced policy to set a floor of 55% under the ownership stake of the state in producing mining concessions. In recent comments, the Chief Executive of the Minerals Commission has sought to imply that this history does not count because it encompasses a period of wholesale nationalisation. Fact is, that is simply incorrect.

While one effect of the Mining Operations (Government Participation) Decree of 1972 was the complete nationalisation of some mines, such as the African Manganese Company, some of the privately controlled mines were not nationalised per se. The policy simply led to a government majority of the equity stake in previously privately-held mining firms. However, in virtually all cases, the state’s equity participation went up to 55%, except for those mines it outrightly owned.

As eminent Ghanaian jurists, S.K.B Asante and S.K. Date-Bah have carefully chronicled in their work on joint ventures in the Ghanaian mining industry, the Ghanaian government negotiated an equity stake of 20% in Ashanti Gold Corporation in 1969. How can a negotiated outcome be considered “nationalisation”? After the negotiated joint venture between the government of Ghana and Lornho, the parties went further to negotiate an option for the state to acquire a further 20% in the future if it chose to do so. The government was also given the right to appoint four board members. Even this agreement was highly criticised by experts at the time due to the insufficient care paid to all the tax implications.

It is important to bear in mind that the action of the succeeding Acheampong government to ensure government majority in the mining companies was based on a policy paper published in December 1972. The prescriptions of this paper were to be translated into action by an interdisciplinary committee of experts, drawn from across the different professional strands of society. It was chaired by Dr. S.K.B. Asante. This team went to London to negotiate with Ashanti Gold in respect of the government’s desire to increase its stake. The passing of the decree was part of the negotiating tactics adopted by the government to strengthen the hands of the committee. Below, the principal terms of the final agreement are reproduced by the two aforementioned jurists.

In substance, therefore, if we are to limit ourselves purely to the split of gains between the government and the private investor, then both the purely negotiated 1969 Ghana – Ashanti Gold agreement and the, decree-backed, 1972 agreements between the same parties were better than the recent lithium deal by having offered the State 20% and 55% (compared to the 13% in the lithium deal), respectively, of the total equity in the concession.

Likewise, the various joint ventures that the government continued to enter into following the reforms of the late 1980s saw government take up large equity positions, as was the case in the Konongo Gold Project, where Southern Cross Mining held 70% and the state, 30%.

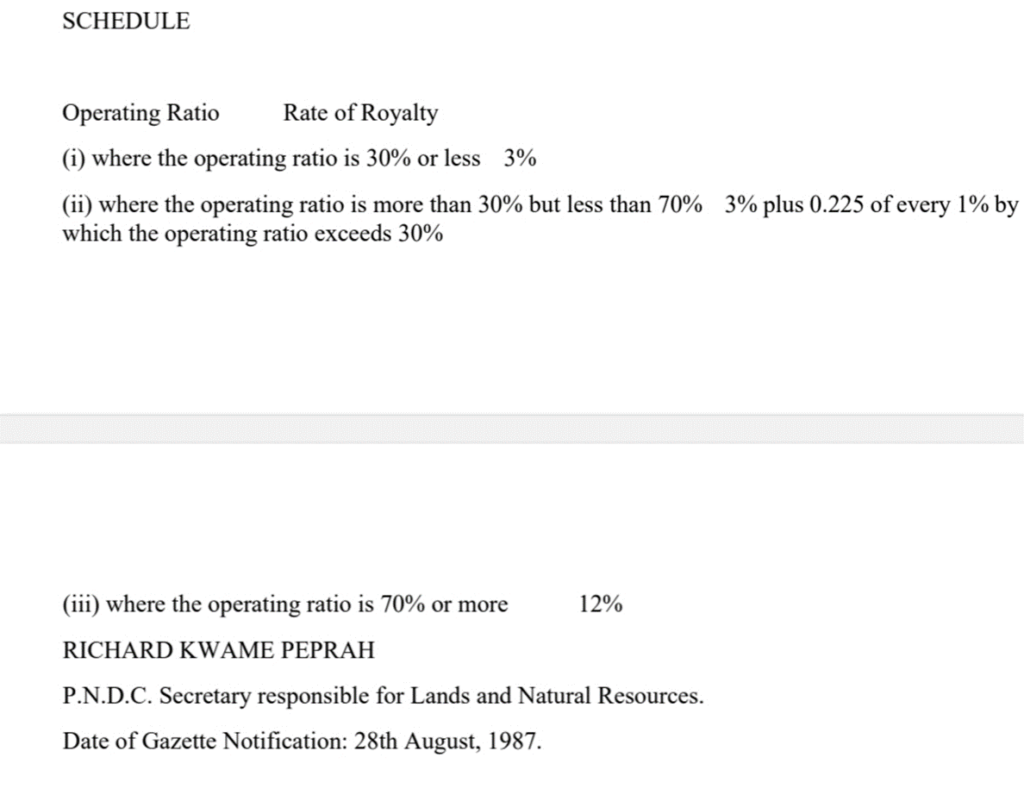

On the issue of royalties, comparison with historic episodes is fraught with confusion because in the past Ghana had a variable rate margin that could take the due royalty entitlement to more than 10%. The 1987 regulations passed during the reform era when Ghana sought to increase private participation in mining again constitute one clear example in this regard.

A windfall arrangement could take the royalty to 12%.

Confining ourselves to the narrow dimension the government of Ghana itself has selected, we can boldly assert that the claim that the terms of the recent lithium deal are the “best” in Ghana’s history is factually inaccurate. It is important that senior civil servants of such high stature strive for objectivity in their public communications.

Another argument canvassed by the Chief Executive of the Minerals Commission is that despite the existence of the variable royalty structures in various contracts historically, and despite his acknowledgement that this could lead to the royalty rate exceeding 10% in these contracts, those terms were in the end meaningless because no mining investor ever paid a royalty rate above 3% (until the Finance Minister in the Mills government initiated a change in royalty rate to 5%). Once again, this claim is contentious, considering the span of mining history in Ghana and the very patent record of joint ventures paying the variable rate based on operating margin. Even in more recent years, we have had companies pay above the royalty treshold, as was the case of the operators of the Chirano mine in 2017.

At any rate, as the AfDB has noted, the failure of the variable tax regime to hit the higher threshold levels is primarily due to the exploitation of loopholes. If duty-bearers and office-holders continue to underperform in their functions, then the history of failure we have witnessed will be due less to the absolute terms found in the various agreements and more to their implementation and enforcement.

To sum up this section, taking the country’s full span of history into account, the lithium deal is not exceptional.

Paperwork is not enough

The heart of the matter though is that nice fiscal terms on paper, however “generous” to Ghana, however “resource nationalistic”, would not mean much if overall management of the sector and/or the investment climate is bad. Contracts and leases should thus be designed in such a manner that they will prove resilient even in the face of weak regulatory performance.

That is why the period when Ghana saw the most nationalistic contracts in the 1970s and 1980s was also the period when it lost its leadership in the African mining sector. Over the course of that era, Ghana’s active gold mines declined from about 34 to just 4. Mismanagement, weak technical capacity, poor investment policies, and a host of factors conspired to prevent the intent of higher social returns to mining from materialising.

Hence why fiscal regimes are hard to compare across countries

Whilst the effort at benchmarking should be highly commended, the government’s selective use of comparative data across African countries to elevate the success of the lithium deal is not as compelling as it could be because it strips some of the numbers of context, uses outdated data, and fails to include instances that are not as favourable for the goals of the comparisons.