The barefoot nun who became a nation’s ‘piano queen’

Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou, the composer and piano-playing nun who died this week at the age of 99, had an extraordinary life, which included being a trailblazer for women’s equality and walking barefoot for a decade in the isolated mountains of northern Ethiopia.

Listening to one of her works can be disconcerting.

It sometimes feels like being tossed around in a small boat at sea, constantly off balance, with little to hold on to. The time signature appears to shift and the scale drifts in and out of familiarity.

The sound of the pioneering pianist reflected the way her life oscillated between parallel worlds.

She was trained in Western classical music but was equally the product of traditional Orthodox Christian chants and tunes.

Her unique musical voice led one critic, Kate Molleson, to argue that Emahoy should be included alongside more familiar names when considering great 20th Century composers.

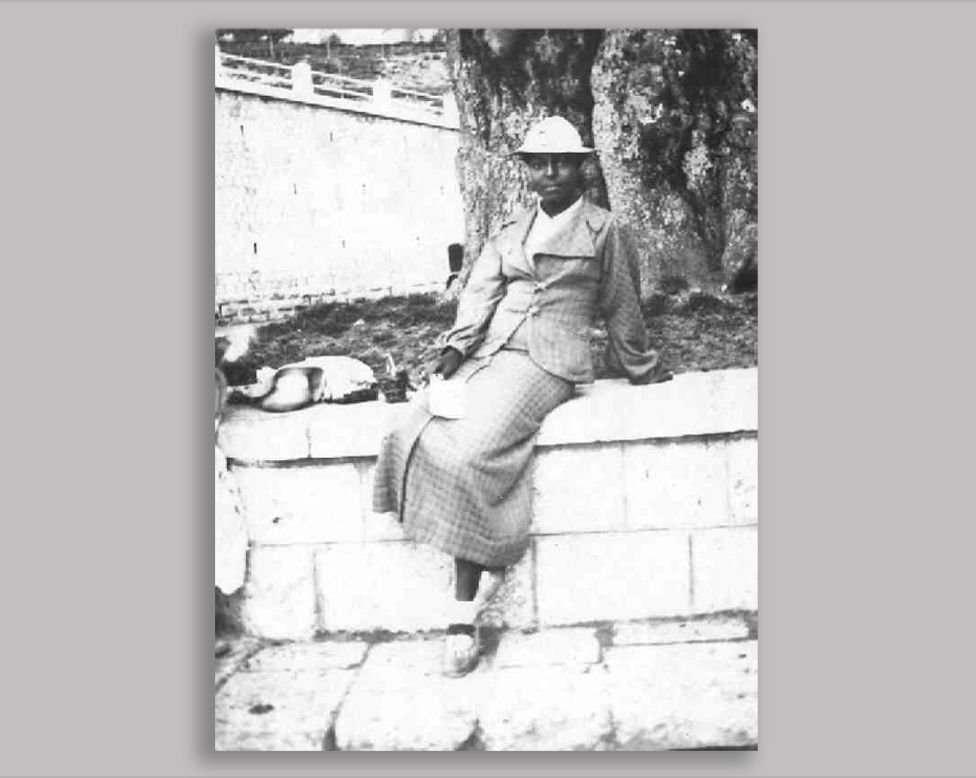

As a young person, Emahoy was a free-spirited modern woman but she spent much of her later life as a reclusive.

She became a devout nun who lived a humble life in a monastery in a remote part of her country. But in an earlier time she had moved in the high society of the capital, Addis Ababa, where she performed in the court of the country’s last Emperor, Haileselassie I.

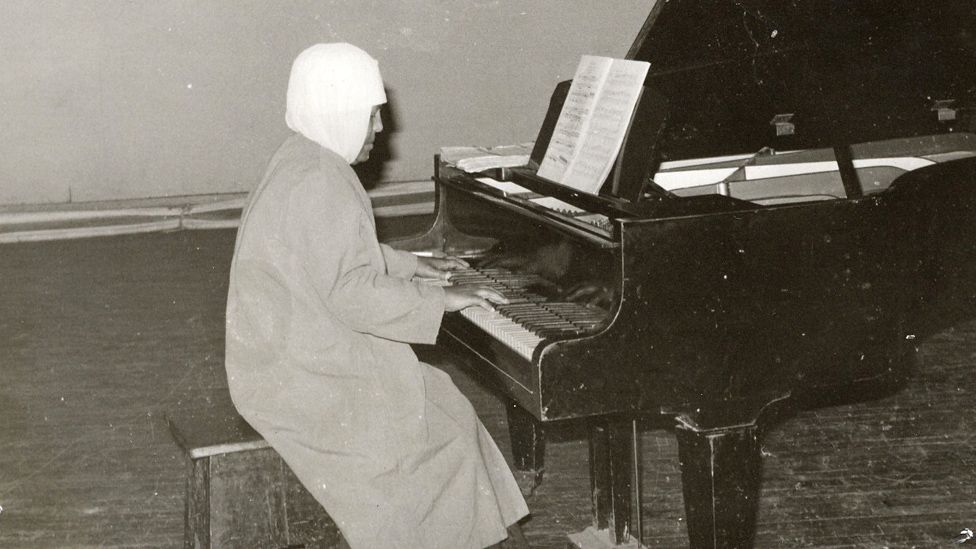

Most of her important musical works – recognisable in their complexity and apparent effortlessness – came in the 1960s and 1970s.

This was during a time when her contemporaries in Addis Ababa were blending Western beats with the Ethiopian pentatonic – or five-note – scale to create a unique fusion of sounds and styles that would later be dubbed Ethio-jazz.

The genre is marked by shuffling soul and funky music as well as big-band swing pieces.

But Emahoy’s compositions and style were distinct. They were just her and her piano producing an intimate, meditative – and unsettling – melancholy informed by a fascinating life punctuated by the momentous events her country experienced during the last century.

She was born in Addis Ababa in December 1923 into a prominent aristocratic family. Her father was a mayor of the historical city of Gondar in the country’s north.

Her given name was Yewubdar – Amharic for “the most beautiful one”- a name she used until she was ordained as a nun at the age of 21.

And with her family came privilege and opportunities.

As a child she was sent to Switzerland with her sister – the first Ethiopian girls to have been sent abroad for education. It was in a Swiss boarding school that she first encountered Western classical music and at the age of eight began playing violin and the piano.

In Europe she felt alienated. “Loneliness grew up with me like a childhood friend,” she said in a book about her father’s life written by her brother, Dawit Gebru.

Music was her consolation.

Upon her return to Ethiopia at the age of 11 she was already an outgoing young girl with an appetite for fashion. But then war and tragedy knocked.

In 1936 Benito Mussolini’s Italy invaded Ethiopia. Three members of her family were killed and she was forced into exile on an island in the Mediterranean. The killing of her relatives left a strong impression on her – later she would compose a song, The Ballad of the Spirits, in their memory.

After five years of occupation, the Italians left Ethiopia and Emahoy returned home where she began work at the ministry of foreign affairs – the first female secretary there. And she drove cars – a rarity for a woman – when the majority of Ethiopians used a horse and cart for travel.

She was determined that her gender would not get in the way.

“Even in my teenage [years] I would say: ‘What is the difference between boys and girls? They are equal,” she told music journalist Molleson for a 2017 BBC documentary about her life.

A few years later she was once again on road.

This time to the Egyptian capital, Cairo, to study music under the Polish violinist Alexander Kontorowicz.

She practised nine hours a day but it was the searing heat that she could not handle. As a consequence, she returned to the cooler climes of Addis Ababa with her teacher, who was appointed the head of the Imperial Guard Band.

While she seemed to enjoy the favours of the emperor for whom she played her music, not all in the aristocratic class were impressed. So when she was given the chance to continue her studies at the Royal Academy of Music in London, she was not permitted to travel – a decision for which her family blame some senior officials.

It changed the trajectory of her life.

Emahoy was heartbroken and sick to the point of being admitted to hospital. Subsequently she took a deep dive into religion. Eventually, she abandoned music – and the city – for a hilltop monastery in a remote part of northern Ethiopia.

She became a nun, shaved her head and stopped wearing shoes.

The death of the monastic community’s archbishop and problems with the souls of her feet led her to return to the capital in her 30s after 10 years of isolation, Molleson says.

She resumed playing music. She continued to shun the spotlight but her compositions took off around this time.

Her years of solitary musings – and the dramatic episodes of her eventful life – were reflected in her compositions. Titles such as The Homeless Wanderer, Mother’s Love and Homesickness hinted at what was on her mind.

“Sadness was always next to me like a friend,” Emahoy was quoted as saying in her brother’s book.

Ethiopian music commentator Sertse Fresibhat called her early works “deep and thoughtful, [composed] at a young age” that received the adulation they deserved only decades later.

She went on to make recordings in Germany in the 1960s and early 1970s to raise money for homeless charities, but only gained notoriety in the West more recently.

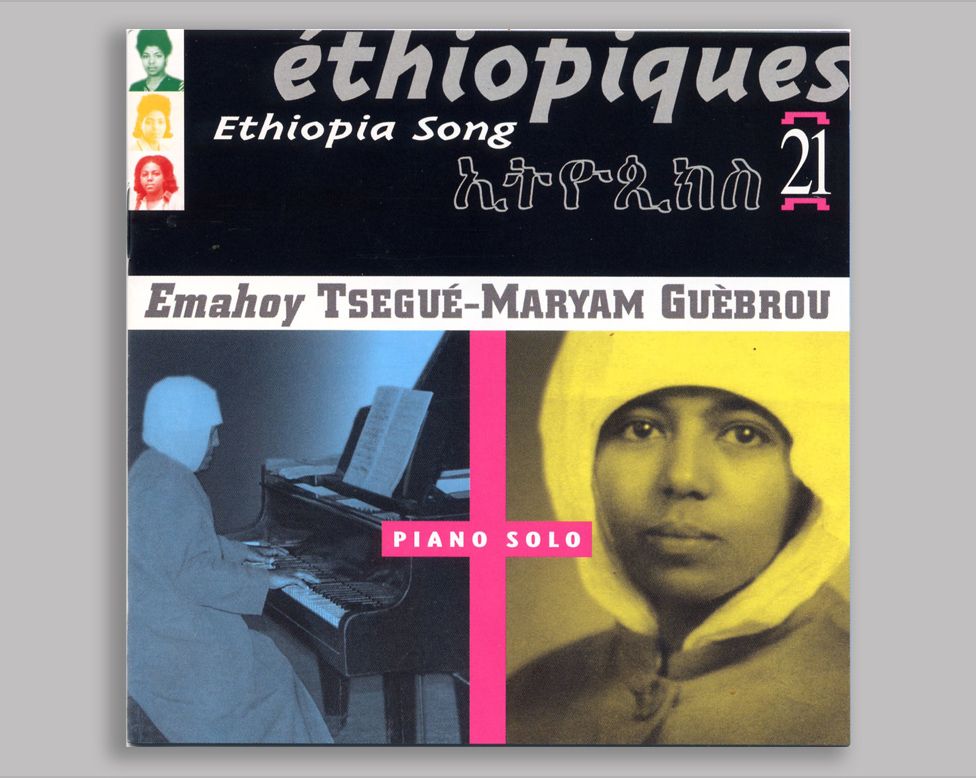

Much like her contemporary Ethio-jazz musicians, she was introduced to the wider audience by French musicologist Francis Falceto. His series of Éthiopiques albums were compilations of archive music from the 1960s and 1970s.

Her collection, released in 2006, gained acclaim and led to her work being used in films and adverts.

But by that time she was living in an Ethiopian Orthodox Church monastery in Jerusalem, Israel.

In 1984, when Ethiopia was in the midst of a civil war and in the grips of a Marxist military regime, she left for the Holy Land and lived the remainder of her life there.

She continued to practise and compose and in her new-found fame welcomed musicologists and critics to discuss her work. She also enlisted Israeli pianist Maya Dunietz to take her manuscripts, and get them published.

In her home country she is often referred as “the Piano Queen”.

Her tunes are everywhere – some are played during periods of national mourning, while others provide background for audio books and radio shows.

But it is possible that many are unaware that they are her compositions.

They have a sense of timelessness that will no doubt continue to find ears and an audience thrilled to learn more about her near-100-year life.