Ghana’s cedi, the world’s second-worst performing currency this year, is heading for more pain after the country missed a self-imposed deadline to restructure its bilateral debt and move closer to tapping foreign aid.

Finance Minister Ken Ofori-Atta wanted to reach a restructuring agreement with bilateral creditors by the end of February to help qualify for a $3 billion International Monetary Fund program.

So far, Ghana has only partially completed the domestic-debt part of the exchange program.

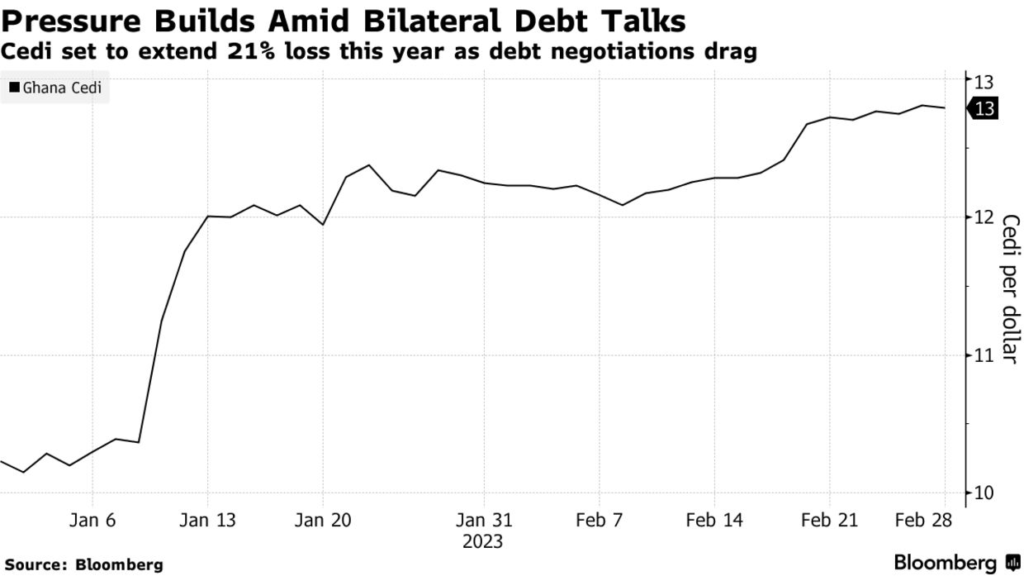

The cedi has slumped 21% against the dollar in 2023, the worst performer among more than 100 currencies tracked by Bloomberg after the Lebanese pound.

Still, the missed deadline doesn’t automatically derail the talks.

Rather, it highlights the difficulties Ghana faces as it tries to reduce its debt load and contend with critics ranging from international bondholders to local trade unions.

“For the foreseeable future the cedi will continue to be volatile until we are able to make substantial progress on the external debt restructuring front,” Kweku Arkoh-Koomson, an economist at Databank Group, said by phone.

“The IMF deal is what will cause a clear stability in the cedi.”

Ghana is trying to restructure most of its public debt, estimated at ¢576 billion ($45 billion) at the end of November.

Local bondholders have been asked to voluntarily exchange ¢130 billion of debt for new bonds that will pay between 8.35% and 15% interest, compared with an average of 19% on old bonds.

Ghana stands to ask external creditors to write off as much as 50% of the debt it owes them — far higher than the 30% the government initially considered, S&P Global Ratings said in a report Tuesday.

“Uncertainty on when the rest of the restructuring will be completed” is influencing cedi volatility, said Courage Boti, an economist at Accra-based GCB Capital Ltd.

“To the extent that those things are hanging in the balance now — in that timelines are not very certain — the volatility of the cedi will continue.”

To date, local investors have exchanged ¢87.8 billion, or 67.5% of bonds under restructuring, for new securities, against an overall target of 80%.

The country will have to reorganize obligations owed to local pension funds to complete the domestic exchange, a move that’s running into criticism from trade unions.

The government aims to start “substantive” discussions with international bondholders and their advisers in the coming weeks, Ofori-Atta said last month, offering eurobond holders some losses while seeking to reschedule payments on bilateral obligations.