Buying a baby on Nairobi’s black market

Somewhere, Rebecca’s son is 10. He could be in Nairobi, where she lives, or he could be somewhere else. He could, she knows in her heart, be dead.

The last time she saw him, Lawrence Josiah, her firstborn son, he was one. She was 16. It was about 2am one night in March 2011 and Rebecca was drowsy from sniffing a handkerchief doused in jet fuel — a cheap high on the city’s streets.

She sniffed jet fuel because it gave her the confidence to go up to strangers and beg. By the time she was 15, Rebecca’s mother could no longer support her or pay her school fees, and she dropped out and slid into life on the street.

She met an older man who promised to marry her but instead made her pregnant and left. The following year Lawrence Josiah was born, and Rebecca raised him for a year and a few months until she closed her eyes that night and never saw him again.

“Even though I have other kids, he was my firstborn, he made me a mother,” she said, fighting back tears. “I have searched in every children’s centre, in Kiambu, Kayole, and I have never found him.”

Rebecca still lives on the same streets in Nairobi. She is small, with sharp cheekbones and short, tightly braided hair. She has three more children now — girls aged eight, six, and four. The youngest girl was grabbed once, she said, by a man who’d been hanging around the area.

He claimed the barely one-year-old girl had asked him to buy her a drink. Rebecca followed him to a car afterwards, she said, where a woman was waiting. The next day, he was back.

You do not have to look hard to find similar stories around the streets where Rebecca lives, alongside other unhoused Nairobi residents. Esther’s three-year-old son disappeared in August 2018. “I have never been at peace since I lost my child,” she said.

“I have searched for him all the way to Mombasa.” It’s been five years since Carol’s two-year-old son was snatched in the middle of the night. “I loved him so much,” she said. “I would forgive them if they would just give me back my child.”

Vulnerable women are being preyed on in Nairobi to feed a thriving black market for babies. Over the course of a year-long investigation, Africa Eye has found evidence of children being snatched from homeless mothers and sold for massive profits. We uncovered illegal child trafficking in street clinics and babies being stolen to order at a major government-run hospital.

And in an effort to expose those abusing government positions, we arranged to purchase an abandoned child from a hospital official, who used legitimate paperwork to take custody of a two-week old boy before selling him directly to us.

The baby-stealers range from vulnerable opportunists to organised criminals — often both elements working together. Among the opportunists are women like Anita, a heavy drinker and drug user who herself lives on and off the street, and makes money stealing children from women like Rebecca — targeting mothers with infants under the age of three.

Africa Eye found out about Anita through a friend of hers, who wanted to remain anonymous. The friend, who asked to be called Emma, said Anita had different methods for snatching children on the street.

“Sometimes she will speak to the mother first, to try and see if the mother knows what she plans to do,” Emma said. “Sometimes she will drug the mother, give her sleeping pills or glue. Sometimes she will play with the kid.

“Anita has a lot of ways to get kids.”

Posing as potential buyers, Africa Eye set up a meeting with Anita in a pub in downtown Nairobi frequented by street sellers. Anita told us she was under pressure from her boss to steal more children, and she described a recent abduction.

“The mother was new to the streets, she seemed to be confused, not aware of what was going on,” she said. “She trusted me with her child. Now I have the child.”

Anita said her boss was a local businesswoman who bought stolen babies from petty criminals and sold them for a profit. Some of the customers were “women who are barren, so for them this is a kind of adoption,” she said, but “some use them for sacrifices”.

“Yes, they are used for sacrifices. These children just disappear from the streets and they are never seen again.”

That dark hint echoed something Emma had already told us, that Anita said some buyers “take the kids for rituals”.

In reality, once Anita has sold a child on, she knows little about their fate. She sells them to the businesswoman for 50,000 shillings for a girl or 80,000 shillings for a boy, she said — £350 or £550. That is roughly the going rate in Nairobi to steal a child from a woman on the street.

“The businesswoman, she never says the business she does with the kids,” Emma said. “I asked Anita does she know what the woman does with them, and she told me she could not care less whether she takes them to witchcraft or whatever. As long as she has money, she does not ask.”

Soon after the first meeting, Anita called to arrange another. When we arrived, she was sitting with a baby girl who she said was five months old and she had just snatched moments before, after winning the mother’s trust.

“She gave it to me for a second and I ran away with it,” she said.

Anita said she had a buyer lined up to purchase the girl for 50,000 shillings. Emma, our source, attempted to intervene, saying she had been introduced to a buyer who could pay 80,000.

“That is good,” Anita said. “Let’s seal the deal up for tomorrow.”

A meeting was set for 5pm. Because a child’s life was in danger, Africa Eye informed the police, who set up a sting operation to arrest Anita and rescue the child, once our buyer had met her. It was likely to be the last opportunity to secure this baby girl before she disappeared.

But Anita never showed up, and despite trying for days we were unable to find her. Weeks later, Emma finally tracked her down. She told us Anita said she had found a higher bidder and used the money to build a two-room, tin-sheet house in one of the city’s slums. The child was gone. The police still have an open file on Anita.

‘Suppose we do this’

There are no reliable statistics on child trafficking in Kenya — no government reports, no comprehensive national surveys. The agencies responsible for finding missing children and tracking the black market are under-resourced and under-staffed.

One of the few safeguards for mothers whose children are taken is Missing Child Kenya, an NGO founded and run by Maryana Munyendo. In its four years in operation, the organisation has worked on about 600 cases, Munyendo said.

“This is a very big issue in Kenya but it is under-reported. At Missing Child Kenya we have barely scratched the surface.” The issue had “not been prioritised in action response plans for social welfare,” she said.

That is partly because this is a crime whose victims tend to be vulnerable, voiceless women like Rebecca, who do not have the resources or social capital to draw media attention or drive action from the authorities.

“The under-reporting has a strong correlation to the economic status of the victims,” Munyendo said. “They lack the resources, networks and information to be able go somewhere and say, ‘Hey, can someone follow up on my missing child?'”

The driving force behind the black market is a persistent cultural stigma around infertility. “Infertility is not a good thing for a woman in an African marriage,” Munyendo said. “You are expected to have a child and it should be a boy.

If you can’t, you might get kicked out of your home. So what do you do? You steal a child.”

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY

A woman in that situation will most likely be put in touch with a trafficker like Anita’s boss, who uses vulnerable people like Anita to snatch children on the street. Or they might be connected to someone with access to a hospital.

According to Africa Eye’s research, child-trafficking rings are operating within the walls of some of Nairobi’s biggest government-run hospitals. Through a source, we approached Fred Leparan, a clinical social worker at Mama Lucy Kibaki hospital. It is Leparan’s job to protect the wellbeing of vulnerable children born at Mama Lucy. But our source said Leparan was directly involved in trafficking. The source arranged to meet Leparan, and told him he knew of a woman desperate to purchase a child after failing to conceive.

“I have this baby boy in the hospital,” Leparan replied. “They dropped him off two weeks ago and never came back.”

According to our source, this was not the first time Leparan had arranged to sell a child.

“The last case scared me,” Leparan said in the meeting, which Africa Eye recorded. “Suppose we do this, I want a plan that won’t cause us problems later on,” he said.

Children like the abandoned baby boy on offer from Leparan should be taken to a government children’s home while they are placed officially with foster parents who have been subject to background and welfare checks. When they are sold illegally by people like Fred Leparan, nobody really knows where they will end up.

Posing as a woman called Rose, an undercover reporter working for Africa Eye met Leparan at an office close to the hospital. Leparan asked a few cursory questions about Rose’s status. She said she was married but could not conceive, and was under pressure from her husband’s family to give birth.

“Have you tried adoption?” Leparan asked.

“We thought about it but it seems like it is a bit complicated,” Rose replied.

With that, Leparan agreed. The price would be 300,000 shillings — £2,000.

“If we go ahead with this deal it will only be the three of us – me, you and him,” he said, pointing to Rose and our source. “My issue is trusting someone. It is very risky. It worries me a lot.”

He said he would be in touch to arrange the sale.

Adama’s choice

Between the street snatchers like Anita and the corrupt officials like Leparan, there is another layer to Nairobi’s child-trafficking business. Dotted around some of the city’s slums you can find illegal street clinics with delivery rooms for expectant mothers. These makeshift clinics are a known location for the black-market trade in babies.

Working with a local journalist, Judith Kanaitha of Ghetto Radio, Africa Eye approached a clinic in Nairobi’s Kayole neighbourhood, home to thousands of the city’s poorest residents.

According to Kanaitha, the baby trade is booming in Kayole.

The clinic we approached is operated by a woman known as Mary Auma, who said she had worked as a nurse in some of Nairobi’s biggest hospitals. Kanaitha posed as a buyer. Inside the clinic, two women were already in labour.

“This one, she is eight-and-a-half months pregnant, she is almost ready to deliver,” Auma said, whispering. She offered to sell the unborn child to Kanaitha for 45,000 shillings — £315.

Auma did not appear concerned for the mother’s welfare after the birth. “As soon as she gets her money, she will go,” she said, waving her hand. “We make it clear, they never come back.”

The woman in the clinic that day whose unborn baby Auma was negotiating for sale was Adama.

Adama was broke. Like Rebecca, she had been abandoned by the man who got her pregnant, and the pregnancy had cost her her job on a construction site when she could no longer carry heavy bags of cement. For three months, her landlord gave her grace, then he kicked her out and boarded the place up.

So Adama decided to sell her baby. Mary Auma was not offering her the 45,000 shillings she was attempting to charge us. She told Adama the deal was for just 10,000 — £70.

“Her place was dirty, she would use a small container for blood, she had no basin, and the bed was not clean,” Adama said later, in an interview in her village. “But I was desperate and I didn’t have a choice.”

Adama said that the day we walked into the clinic, Mary Auma had just induced her, without warning, by giving her tablets to swallow. Auma had a buyer and was keen to make a sale.

But the birth was not smooth. The baby boy had chest issues and Auma told Adama to take him to Mama Lucy hospital for treatment. After two weeks, Adama was discharged with the baby. She texted Auma, and Auma texted us.

“New package has been born,” she wrote. “45,000k.”

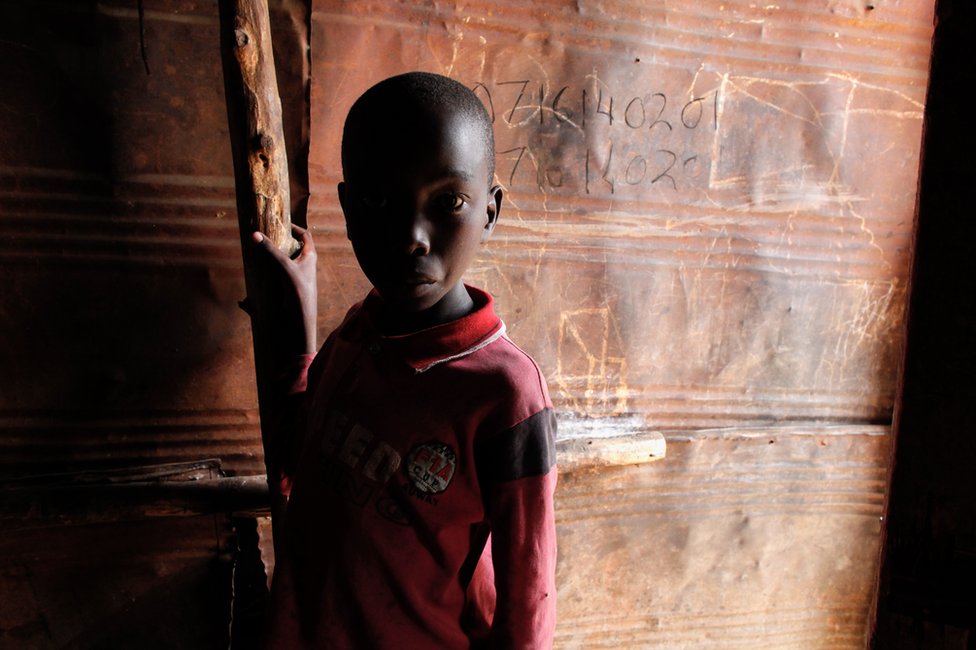

IMAGE COPYRIGHTTONY KARUMBA

IMAGE COPYRIGHTTONY KARUMBA

At the clinic, Adama was reunited with Auma and her assistant. “They said the baby looked OK and if the client wanted him he would be taken straightaway,” she said.

Adama had made a painful choice to sell her child. Now she was reconsidering.

“I did not want to sell my baby to someone who would not be able to take care of him, or someone who buys babies to go use them for other things,” she said later.

So Adama left the clinic that day carrying her baby boy. She dropped him instead at the government-run children’s hospital, where he would wait for foster parents and, she hoped, a better life.

She never got the money she needed. She lives alone now, away from Nairobi, and sometimes she dreams about her son and wakes in the early hours and thinks about him. Sometimes, if she can’t get back to sleep, she walks down the road in the dark until she finds someone else awake. But she doesn’t regret her choice.

“I feel at peace to have given my baby to the government,” she said, “because I know he is safe.”

The hospital sale

Fred Leparan, the clinical social worker at the government hospital, called to say he had identified a baby boy given up by his mother that he wanted to steal for us. The boy was one of three children at the hospital waiting to be transferred to a nearby children’s home. It was Leparan’s job to ensure they got there safely.

But Leparan knew that once the babies left Mama Lucy hospital, there was only a slim chance anyone from there would check they had arrived at the home.

At the hospital, Leparan filled out the necessary paperwork and made small talk with the staff, who had no idea that a child was being stolen on their watch.

Rose, the undercover reporter, was waiting in a car outside. Leparan told the hospital nurses she worked for the children’s home and asked them to take the babies out to her. He seemed increasingly anxious, but he assured our source that the nurses would not follow them.

“No, they can’t, they have work to do,” he said. Then he urged the team to leave quickly. “If we keep chatting like this someone may suspect,” he said.

Moments later, the team drove out of Mama Lucy hospital with three infant children in the car and instructions to deliver just two of them to the children’s home. From there, the third baby could have gone anywhere, to anyone.

The undercover team delivered all three children safely to the home, where they will be cared for until a legitimate adoption can be arranged.

Later that afternoon, Leparan called Rose to a meeting and instructed her to place the agreed 300,000 shillings on the table. He instructed her to see a nutritionist. “The only thing to keep an eye on is the boy’s vaccine mark,” he said.

“Also, be careful. Be very careful.”

The BBC confronted Fred Leparan about this transaction but he refused to comment. The hospital also declined requests to comment, and Leparan appears to have kept his job.

We also informed a children’s rights NGO about Mary Auma’s illegal street clinic in Kayole, which in turn informed the police. But Auma appears to still be in business. She did not respond when we put our allegations to her.

And we attempted to put our allegations to Anita, but she seemed to have once again disappeared into the shadows of the street.

“We all want to be mothers to our children,” Rebecca said. “It is not our fault we are in the streets.”

For the mothers whose children were stolen, there will never be any real resolution. Most go on in limbo, hoping to see their child again, knowing that they probably won’t. Rebecca would give “everything” to see her son, she said. “And if he died I would like to know too.”

Last year, she heard that someone saw a boy in a distant neighbourhood of Nairobi that looked just like her eldest daughter, Lawrence Josiah’s sister. Rebecca knew it was probably nothing, and she had no way of getting to the neighbourhood and no idea where to look if she did. She did get as far as the local police station, but she couldn’t get any help, she said, and eventually she gave up.

“There is a one in a million chance these women will see their children again,” said Maryana Munyendo, from Missing Child Kenya. “Many of the street mothers are children themselves, and they are taken advantage of in their vulnerability.”

People like Rebecca were too often not seen as sympathetic victims of crime, Munyendo said. “But nobody should assume that people on the street do not have feelings, that they do not deserve justice. They do have feelings. The way you miss your child if you live in a suburban area is the same way you miss your child if you are a mother on the street.”

Some of the babies stolen from the street will end up in those suburban areas. Sometimes Rebecca thinks about the wealthier women who paid for them — about what it takes to raise a child you know was stolen from someone else.

“What are they thinking?” she said. “How do they feel?”